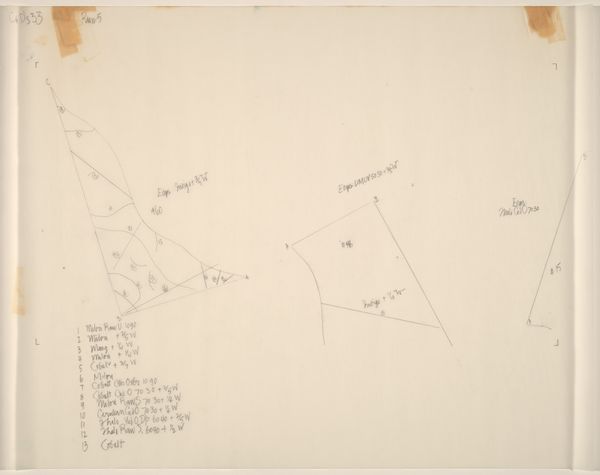

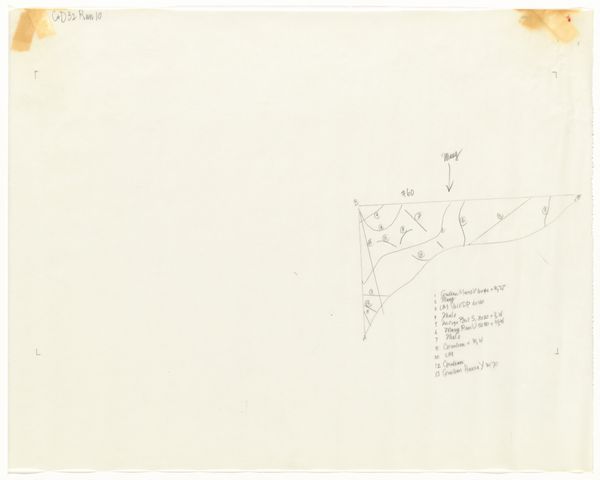

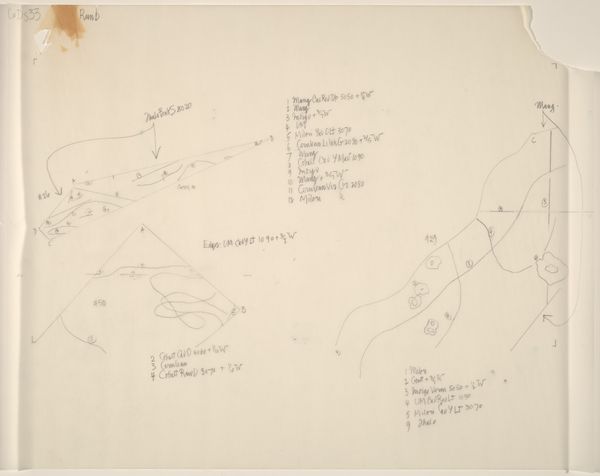

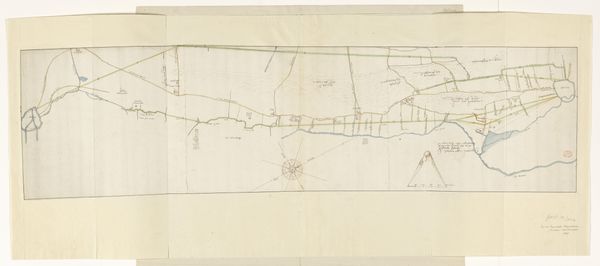

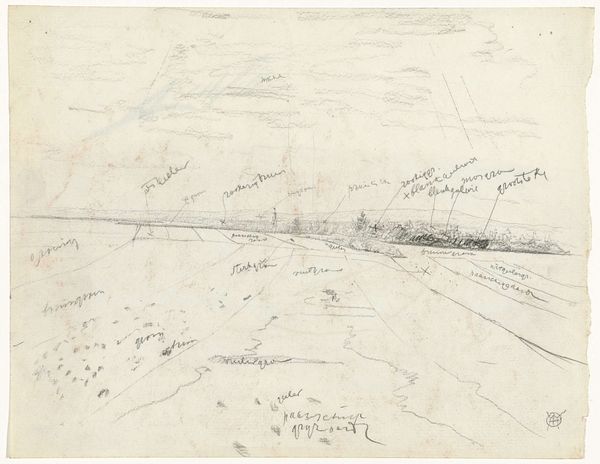

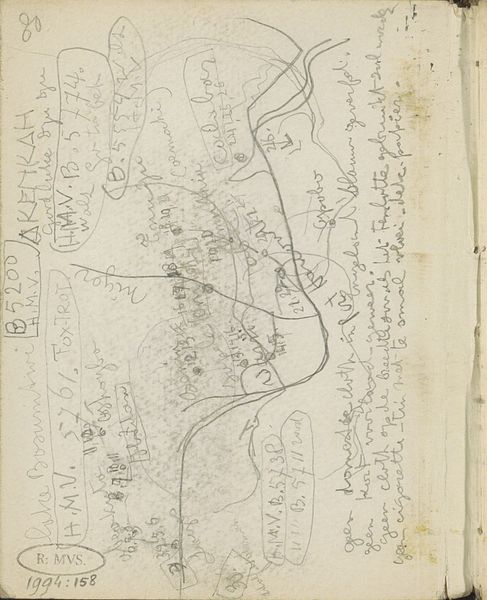

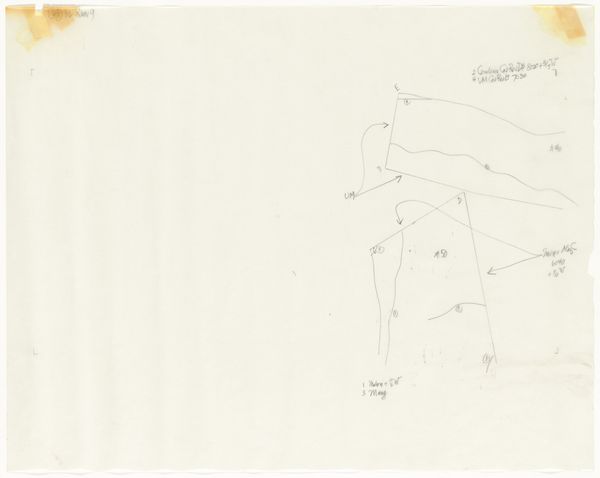

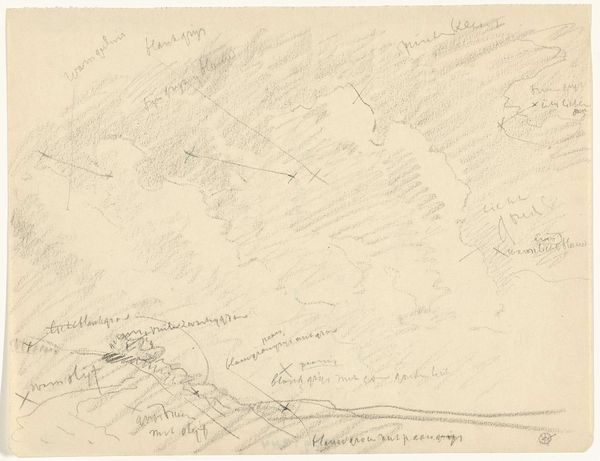

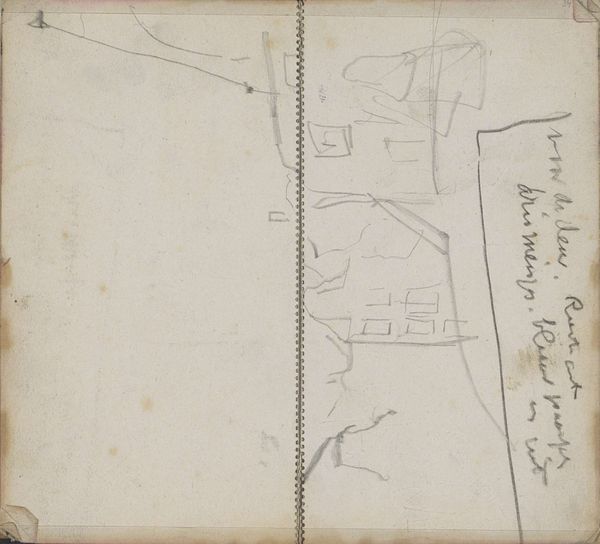

drawing, pencil

#

drawing

#

conceptual-art

#

etching

#

geometric

#

black-mountain-college

#

pencil

#

abstraction

Dimensions: sheet: 48.26 x 60.96 cm (19 x 24 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

Editor: John Cage's "Tracing for Changes and Disappearances #32 (5 of 11)" from 1982, rendered in pencil, feels like a blueprint or a map. There's a delicate fragility to the lines. What do you see in this piece that I might be missing? Curator: I see a meticulous exploration of process and its direct link to the materials used. Consider the "tracing" in the title. It emphasizes Cage’s physical interaction, almost a tactile dialogue with the paper and pencil. These are not precious materials, hinting at the everyday, the accessible. How does this de-emphasizing of high materials influence your reading of it? Editor: I guess it makes it feel less precious, more about the act of creating than the final product itself. Is that what you mean by "labor?" Curator: Precisely. The act of repeated tracing, the visible calculations, the almost scientific notation, speak to a specific labor. Think about the 1980s. Do you find these somewhat crude markings a possible reaction to the slick, mass-produced aesthetic that dominated much of the visual landscape then? Editor: That's a great point. Seeing the hand so directly involved is a powerful counterpoint to that. I see your point about challenging boundaries between "high art" and this more "everyday" type of creating. It becomes a type of record of simple action. Curator: And it opens the question of "finished" versus "process." The pencil markings highlight both the tangible tools used and the artist's physical actions. I think it highlights what can be made with next to nothing. What would happen if we centered "usefulness" or "accessibility" or "process" when determining the worth of artwork? Editor: This makes me think about what *we* value, not just as art appreciators, but more broadly. I’m now re-considering where worth comes from when making any kind of aesthetic or moral judgements.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.