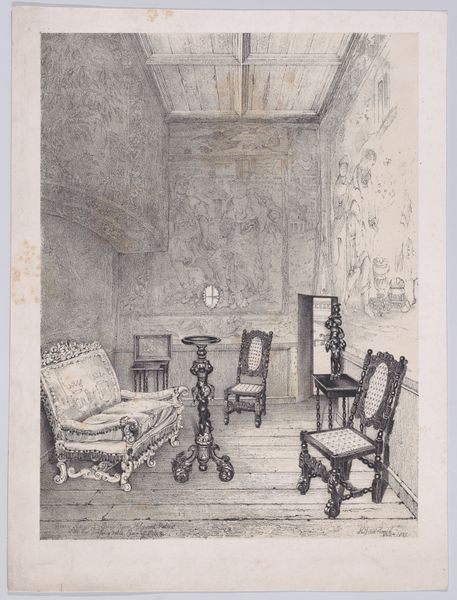

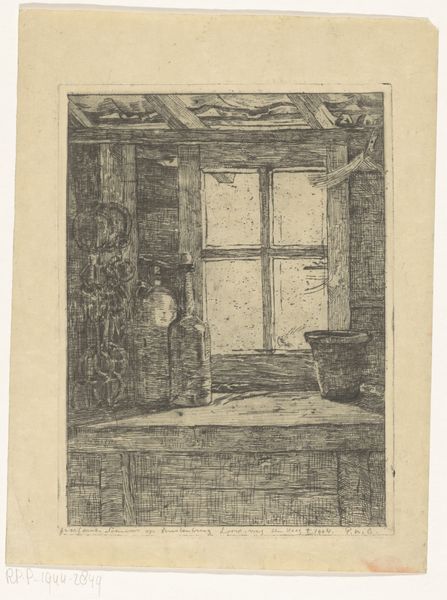

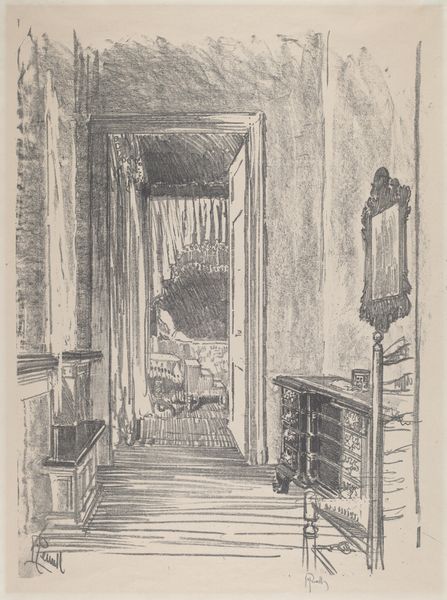

Closet of Mary, Queen of Scots, Holyrood Palace, from which Rizzio was dragged and murdered 1837

0:00

0:00

drawing, print, pencil

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

narrative-art

# print

#

figuration

#

romanticism

#

pencil

#

history-painting

Dimensions: Sheet: 12 15/16 × 9 1/2 in. (32.9 × 24.2 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Samuel Dukinfield Swarbreck created this pencil drawing and print in 1837, titled "Closet of Mary, Queen of Scots, Holyrood Palace, from which Rizzio was dragged and murdered." It’s quite evocative, don't you think? Editor: The stark greyscale palette immediately sets a somber tone, and the perspective pulls you right into that rather confined space. It’s unsettling. Curator: Precisely. The artwork depicts the infamous scene where David Rizzio, Mary’s private secretary, was brutally murdered in front of her. Consider the power dynamics: Mary, a woman ruling in a patriarchal society, her close relationship with Rizzio fueling jealousy and suspicion. The print highlights the vulnerability she faced. Editor: Structurally, the eye is led down the hallway towards that distant doorway, a visual pathway to the exterior and an escape. The sharp contrast between light and shadow exaggerates the claustrophobia of the 'closet,' a small space with very high walls. Note how the furniture in the foreground crowds and constrains the composition, creating a powerful sense of entrapment. Curator: Indeed. Swarbreck used the setting itself to underscore Mary's precarious position and the violence perpetrated against marginalized individuals. The very absence of figures speaks volumes. The tattered state of the room reflects the decay of power and the crumbling of societal norms surrounding gender and authority. The portrait of the man over the mantle—probably Darnley, her jealous husband— looms, too, and reminds us of the social codes and tensions surrounding power. Editor: And what about those ghostly items of apparel arrayed on the table—gloves and a draped mantle—almost as if someone shed their corporeal presence, left as an ephemeral reminder of this ghastly crime? They are almost strategically positioned as compositional guideposts to punctuate the pictorial plane. Curator: An excellent point. Think about how the space, the room, becomes a stage for historical reenactment and the power of place in shaping our understanding of political turmoil. The materiality of the palace is no different than any socialized landscape, it becomes charged through human intervention. Editor: Ultimately, the linear composition serves to deepen the visual symbolism of this intimate and tragic space, the architecture is inextricably linked to a profound historical narrative, one of both intimate betrayal and immense national consequence. Curator: Absolutely, and the work prompts us to question whose narratives are told and how artistic representations contribute to collective memory and shape public sentiment across generations. Editor: I am now struck with a renewed awe for how visual expression can distill space, time and history, and present it to our present-day awareness.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.