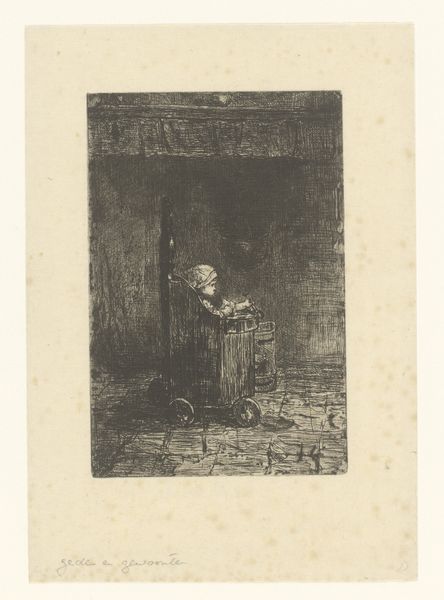

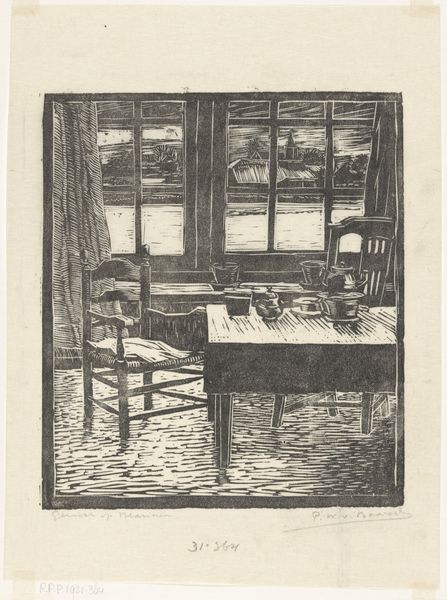

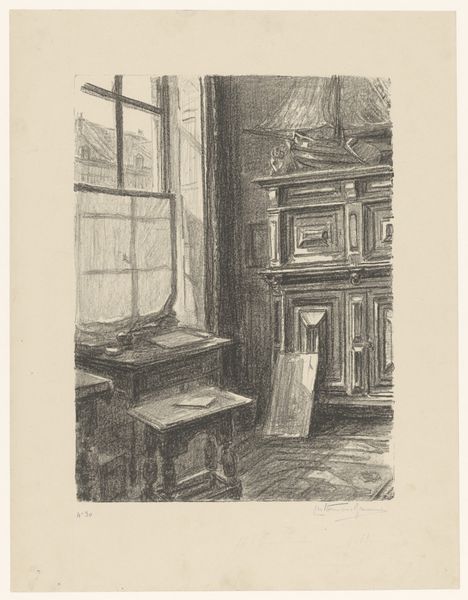

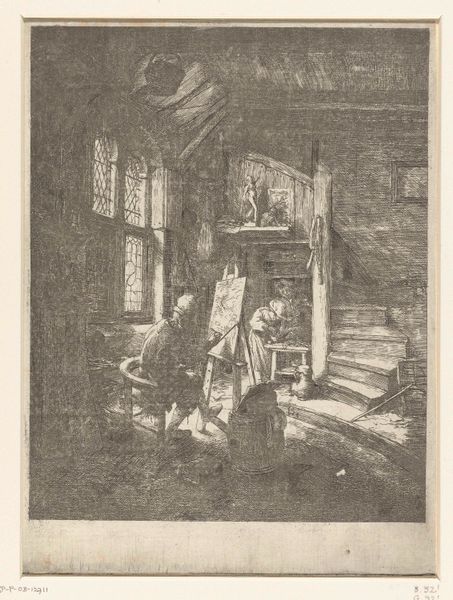

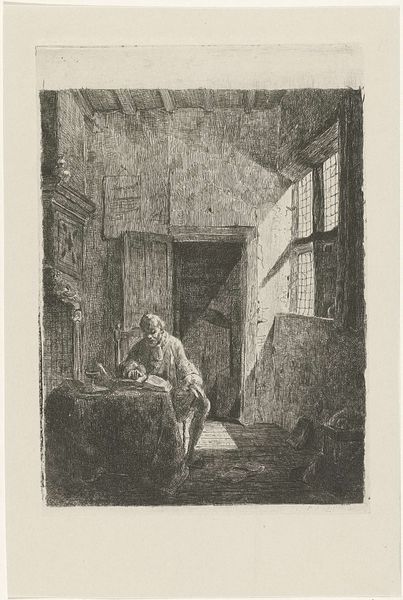

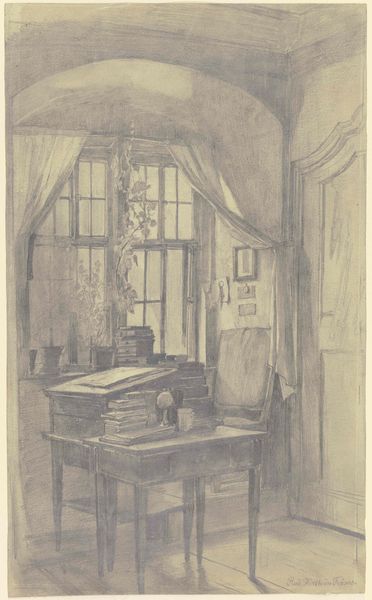

drawing, pen

#

drawing

#

aged paper

#

toned paper

#

light pencil work

#

pencil sketch

#

sketch book

#

personal sketchbook

#

intimism

#

pen-ink sketch

#

sketchbook drawing

#

pen

#

storyboard and sketchbook work

#

sketchbook art

Dimensions: height 213 mm, width 158 mm, height 261 mm, width 199 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: This drawing, "Schuur," was created around 1904 by Pieter Willem van Baarsel. It's a pen and pencil sketch of what appears to be the interior of a shed or barn, rendered on aged paper. The overall mood feels very intimate, like a personal glimpse into a private space. What strikes you most about this piece? Curator: What intrigues me is how van Baarsel uses such simple lines to suggest a complex socio-economic reality. The intimate portrayal of this humble "schuur" – a Dutch word with connotations beyond just a simple barn – forces us to confront questions of labor, rural life, and the artist’s own position within that landscape. This wasn’t just a neutral observation; it’s a deliberate framing. Editor: A deliberate framing, in what sense? Curator: Think about it: the items depicted, the bottles, the hanging tools. These objects silently speak to the lives of those who used the space. Van Baarsel is choosing to represent a working-class environment. What's the narrative he's implicitly constructing, and how does it either reinforce or subvert the dominant social narratives of his time? Is it romanticizing, or simply documenting? The subtle imperfections, the "aged paper," are they merely aesthetic, or do they suggest a certain level of historical or even psychological "wear and tear"? Editor: So, you see it as more than just a simple sketch. It's a commentary on the lives of those who occupied the space? Curator: Exactly! It begs us to question the relationship between the artist, the subject, and the viewer. Who are we, looking at this drawing a century later, and what biases do we bring to our interpretation of this intimate scene of labour? It also brings up class and visibility, and who gets to depict whose reality. Editor: I never thought of it that way. I was only thinking about composition, but now I see how loaded such a seemingly simple drawing can be with social and political meaning. Curator: And that, I think, is the enduring power of art, isn’t it? To open up those avenues of critical thought.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.