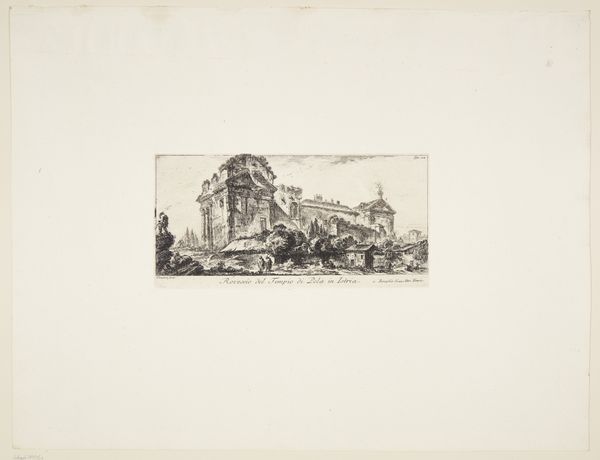

print, engraving, architecture

# print

#

landscape

#

romanesque

#

history-painting

#

engraving

#

architecture

Dimensions: 138 mm (height) x 270 mm (width) (plademaal)

Curator: Piranesi's etching, "Tomb of Metella called Capo di Bove," created around 1748, captures the aura of Roman antiquity with such potent symbolism. The work is held in the collection of the SMK - Statens Museum for Kunst. Editor: The initial impression is striking. The intense contrast immediately conjures feelings of loss and grandeur – the etching technique adds so much to the gravitas of the scene, almost forcing one to imagine an operatic stage. Curator: Exactly, this image exemplifies the artistic dialogue between the grandeur of history and its ruinous decay, an echo from what was to what remains, that speaks to a cyclical interpretation of civilizations rising and falling. The Capo di Bove becomes a silent witness, its stoic facade scarred yet resolute. It prompts questions about the ephemerality of power and the resilience of memory embedded in stones. Editor: Absolutely, and the setting, which combines historical record with the genre of landscape, invites us to project both historical and social meaning onto it. Notice how Piranesi includes small figures within the architecture, reminding us of the living world interwoven with these imposing structures, giving human scale. How would people in the 1740s have seen this interplay of the ancient past with contemporary life, I wonder? Curator: Perhaps with a degree of melancholy, seeing a connection, with both the potential for decline but also rebirth, that all epochs contain symbols of what might become. It’s this ability to make visible an internal psychological state through external imagery, using sharp lines to denote decay but simultaneously survival, which marks the work as powerful. Editor: It leaves one considering the politics inherent in viewing ancient ruins during the eighteenth century. The emphasis isn't only on historical legacy, but on the way such imagery can construct ideas of nationhood, progress, and imperial destiny—to what degree were those in power implicated by viewing it this way? Curator: A sobering reflection. I see the power of cultural memory refigured, etched not just onto paper but into the broader consciousness of the era, shaped by the way we choose to preserve—or reimagine—the symbols of the past. Editor: Indeed. The dialogue between the symbolic, personal, and political realms resonates deeply even now. Thank you for this viewing.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.