drawing, print, engraving

#

drawing

#

allegory

# print

#

sculpture

#

charcoal drawing

#

mannerism

#

figuration

#

11_renaissance

#

history-painting

#

charcoal

#

engraving

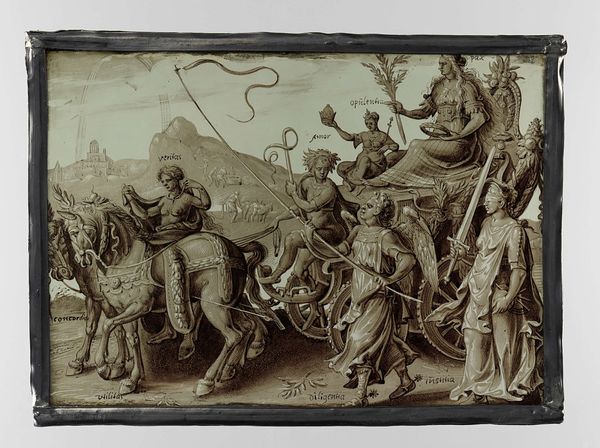

Dimensions: height 20.5 cm, width 28.0 cm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This engraving, titled "Ruit met De Triomf van de Hoogmoed (Superbia)", comes to us from around 1575 to 1600 and is currently held at the Rijksmuseum. What strikes you initially about this image? Editor: It feels incredibly theatrical, almost like a stage tableau. The figures are so dramatically posed, and the use of light and shadow really amplifies the sense of heightened emotion, particularly a disturbing one. Curator: That theatricality is very characteristic of Mannerism, the artistic style of the time. Artists were striving for elegance, sophistication, and often deliberately distorted forms and exaggerated emotions. We are far away from classicisim. Editor: That certainly explains the somewhat unsettling feeling I get from the figures' elongated limbs and expressive gestures. And what is she doing with that mirror? Is she admiring herself? Curator: Precisely. This print allegorically represents Superbia, or Pride, one of the seven deadly sins. Notice how she's enthroned in a chariot, attended by figures representing vanity and insolence, the trappings of worldly power at her command. Editor: The mirror certainly speaks to the sin of vanity. It’s not merely about physical appearance; it's the arrogance and self-absorption that consume and corrupt. Curator: And the figures in the chariot with her – they embody that corruption, don't they? The whip signifies dominion. The chariot itself, traditionally a symbol of triumph, is here twisted to represent the victory of moral failing. Editor: It's a fascinating inversion. It takes something that is expected to uplift—a triumphant chariot—and subverts it to display a moral failing. So Pride, in this context, is not simply about ego, but it is the perversion of legitimate authority into self-serving excess. It has profound social implications, especially among the Renaissance elites of that time, doesn’t it? Curator: Absolutely. The artist, though anonymous, uses the visual language of allegory to deliver a potent social critique of unchecked power and moral decay, echoing anxieties around corruption during that era. Editor: I'm left pondering the enduring nature of these allegories. How often do we still witness this "Triumph of Pride" playing out in different guises today? Curator: Indeed. It invites us to recognize these timeless vices within ourselves and our own societies.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.