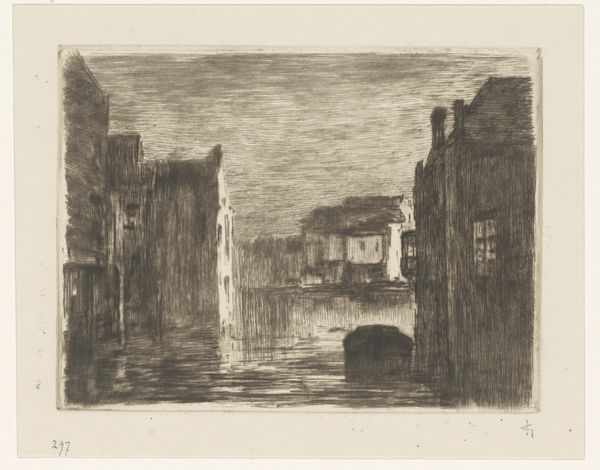

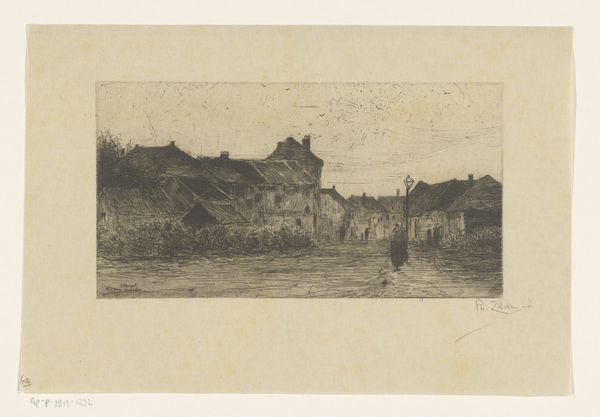

drawing, graphite

#

pencil drawn

#

drawing

#

pencil sketch

#

landscape

#

pencil drawing

#

graphite

#

cityscape

#

realism

Dimensions: height 139 mm, width 200 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

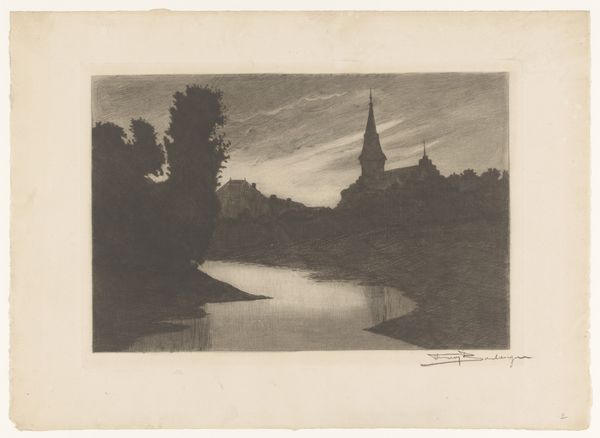

Curator: Etha Fles gifted us this delicate pencil and graphite cityscape called "IJsselstein." It's said to be from somewhere between 1867 and 1910. Editor: It's instantly evocative. The whole thing feels dreamlike, shrouded in memory or perhaps a touch of melancholy. What strikes you about the way the piece makes us consider a tangible relationship with space? Curator: Definitely! I get the melancholy, too. There is the striking lack of people, and only light reflected on the water lends it a spectral sense. But Fles offers us the weight of buildings, even in graphite, as if daring to define a relationship with history as more solid than fleeting human life. Editor: This emphasis is interesting when thinking about IJsselstein and its importance as a refuge for freethinkers. Perhaps, it reflects how such spaces are molded and sustained by collective thought. Note, especially, the emphasis on domestic architecture and how this focus encourages the viewers to focus more on community-building, the role of domestic space, or a gendered element to this visual tale. Curator: Ooh, I like that interpretation. To me, there is this balance between the intimacy of a town and then the aspiration of the windmill… pointing, you know, somewhere… but where? Editor: Exactly! This reaching towards progress intersects here with the grounded lives of the town's inhabitants. But who has the luxury to ponder about such aspiration, when, in contrast, not everyone is equally housed, fed, safe? Does art, by capturing these nuances, offer a glimpse into social equity and distribution of care? Curator: The way she handles the light is so interesting, too. Like, you want to see the buildings sharply, but there is also this softening of edges. As if Fles herself couldn’t quite grasp the clarity. Or, perhaps, as a signal not to define too closely the past? Editor: It begs the question of what are we meant to leave behind as a civilization, when so often what is considered worthy elides questions of communal care. The interplay of light and shadow, which at first feels aesthetic, begins to point toward very material concerns. Curator: It makes me want to walk through that little bridge… see where it leads. So, it really does invite this conversation about social structures versus physical location, it’s truly magical, right? Editor: It really is! A reminder that art persists to reflect and critique who we have been, and consider who we might become, hopefully more conscious, ethical, together.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.