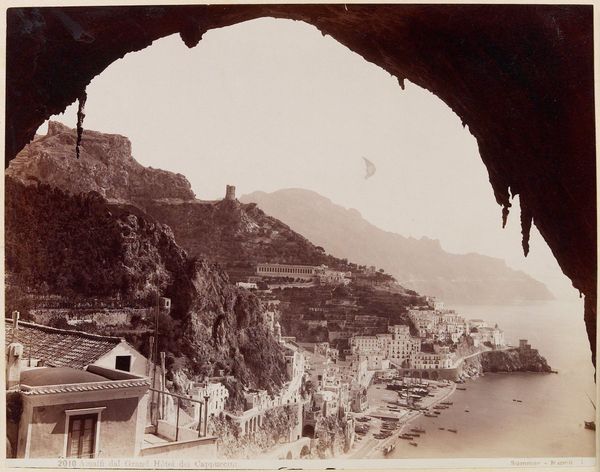

photography, albumen-print

#

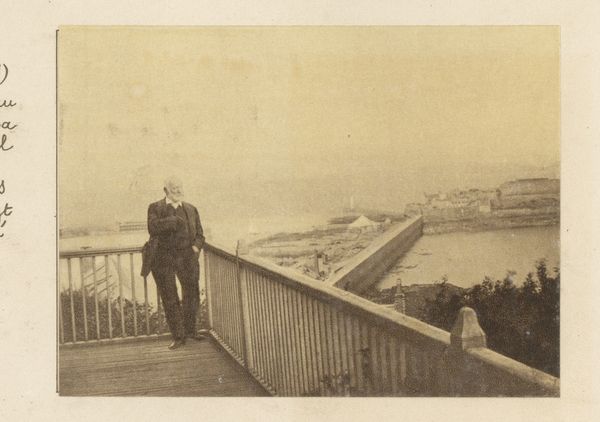

portrait

#

16_19th-century

#

sculpture

#

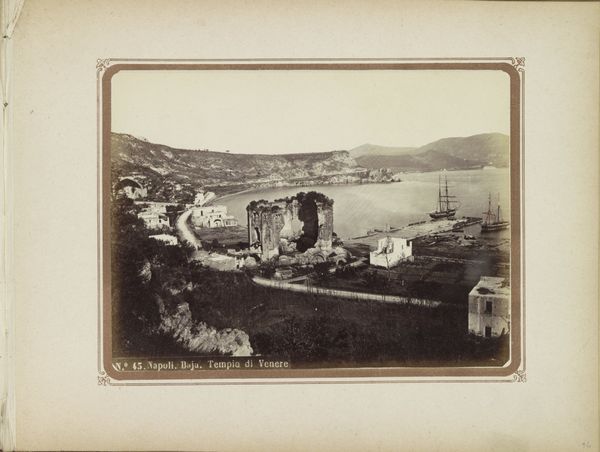

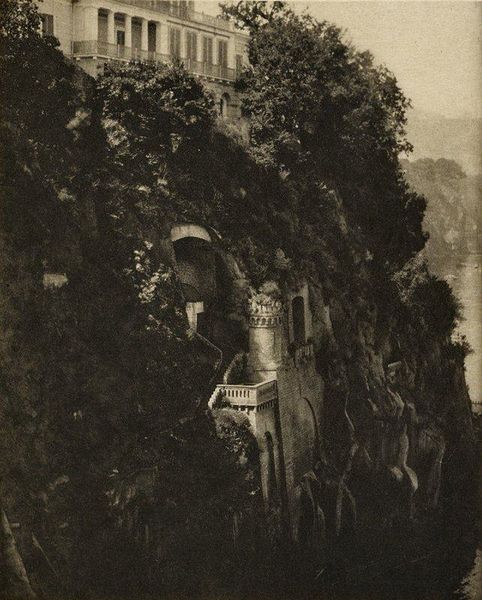

landscape

#

photography

#

orientalism

#

cityscape

#

albumen-print

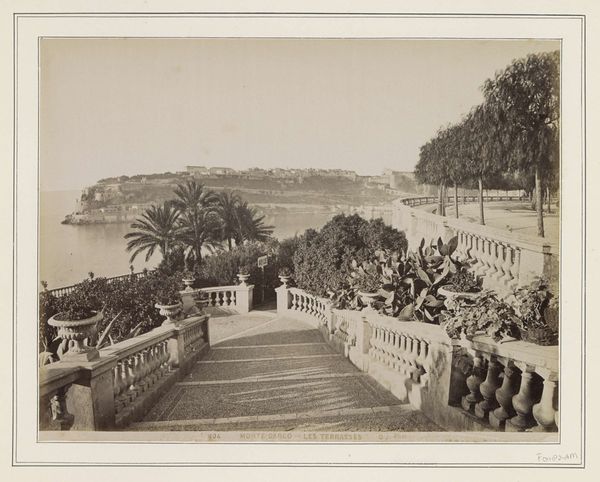

Dimensions: height 200 mm, width 252 mm, height 309 mm, width 507 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

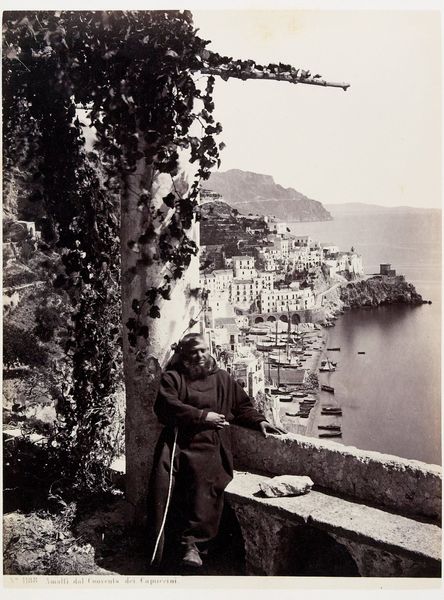

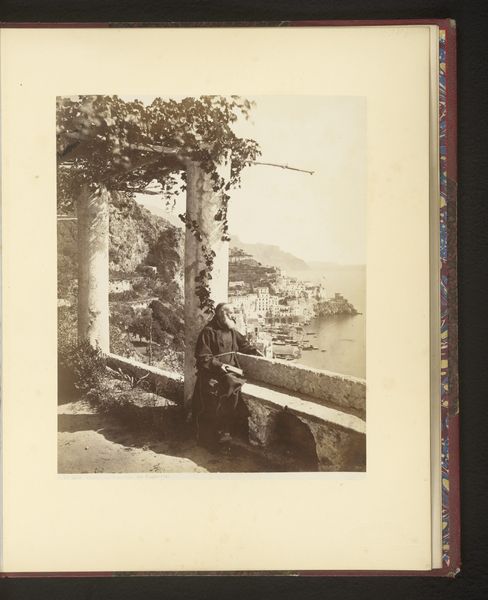

Curator: What a wonderfully serene image. I am drawn to the sense of peaceful contemplation. Editor: Yes, there's definitely a contemplative air about it. This is "Amalfi," an albumen print photograph created by Giorgio Sommer, likely sometime between 1888 and 1903. The Rijksmuseum holds this print in their collection. Curator: Thank you, that helps situate us in the historical context. For me, the key figure here is the monk. It begs so many questions, doesn't it? Who was he, what's his story, what’s his relationship to the depicted site? How does he perceive his relation with this landscape? His solitary presence set against the dramatic vista prompts an exploration of identity, faith, and perhaps even an unconscious desire. Editor: Absolutely. And it speaks volumes about the social and political context of that period. Photography like this played a significant role in shaping perceptions of place and cultural identity, contributing to how Amalfi and Southern Italy were seen at the time. This romantic image taps into both the Grand Tour tradition and also to orientalist perceptions of a life lived under an assumed spiritual calm. Curator: The positioning of the monk is striking. Leaning on the wall of the terrace, overlooking the sea—there is a kind of active observation in stillness here, almost melancholic…It speaks volumes about power dynamics too—who has access to these breathtaking views, and who is capturing them for broader consumption? Editor: It brings up some very real tensions—access, tourism, even colonial undertones are at play in the representation of this landscape. What is not represented? Sommer does not focus on labour; and so presents the scene without necessary reference to a system that grants some time and leisured contemplation in nature. We also have to remember the institutional power behind what and how such images were made. Sommer had relationships with museums; this work would circulate into various publics who were shaped to regard Italy and its inhabitants in a certain fashion. Curator: It definitely seems an attempt to romanticise Italian monastic orders. By overlooking labour and portraying only its most "spiritual" agents, he seems to grant dignity to the subjects—though ultimately, at a distance. That's quite problematic given Italy's history. Editor: Indeed. And in that light, the image opens to interpretations around tourism, privilege, and the selective framing of a specific cultural narrative. I wonder, if presented this scene to contemporary communities in Southern Italy, what would be their first reading. Curator: An interesting question that shows how the legacy of images continues resonating today and influencing socio-cultural discussions across boundaries. Editor: Precisely, and remembering that keeps such dialogue relevant to the politics of visuality.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.