daguerreotype, photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

daguerreotype

#

photography

#

historical photography

#

historical fashion

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

19th century

#

history-painting

#

academic-art

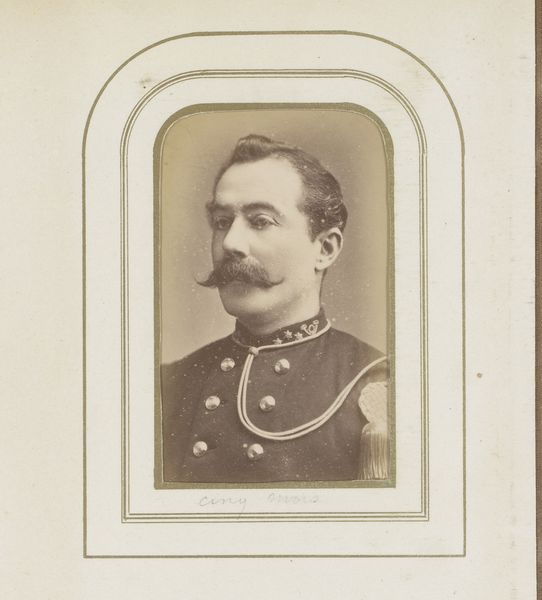

Dimensions: height 83 mm, width 50 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

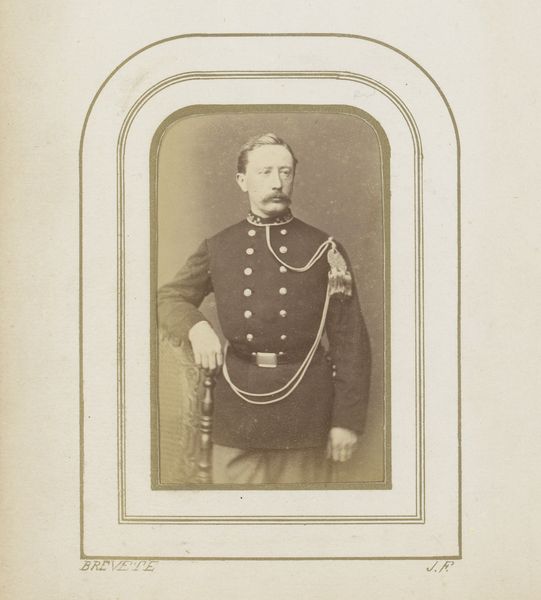

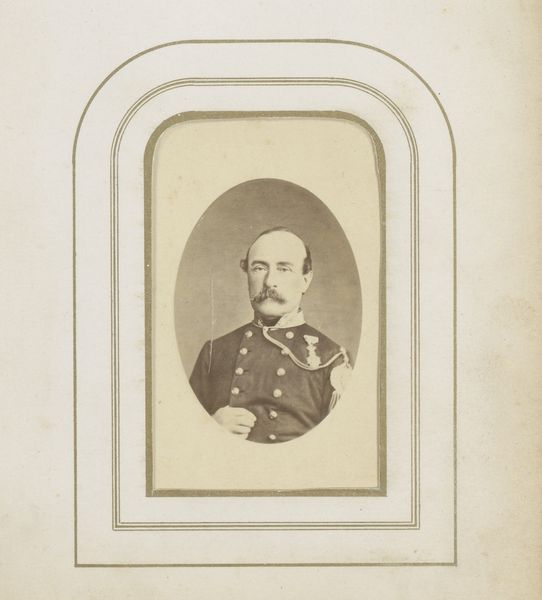

Editor: Here we have a gelatin silver print titled "Portret van een man met zwaard in uniform" by Charles Billotte & Cie., made around 1861. There's something so commanding about this figure and his crisp uniform, yet also subdued in the tonality. How should we interpret the social implications behind images such as this? Curator: This portrait offers a glimpse into the mid-19th century and the power structures embedded within it. Military uniforms weren't merely functional; they were carefully designed visual statements of authority and social standing. Consider the daguerreotype process itself; it made image production more democratic and catered to a rising middle class, who aspired to possess portraiture, like the elite. What does the uniformity of early photography suggest to you? Editor: That's an insightful connection between the subject and the medium. It feels like these types of early photographs, more so than paintings, grant some sort of level of validation or believability to the person in the photograph. I hadn’t thought of photography as making images "more democratic," I rather naively saw paintings of similar portraiture as superior given the length of production and associated costs. Curator: And it is that very understanding of historical value being associated with "painstakingly crafted" artistry and the ability to commission work that reinforces hierarchical ideas that society should reconsider! It goes back to understanding that social hierarchies often dictate both the production AND the reception of art. What stories might be excluded or misrepresented through this particular lens? Editor: So true! While we have an imposing figure displayed before us, there were many more that existed outside this particular social group, perhaps those that held similar military rankings from a lower socioeconomic status, who did not have access or the money to buy art, and thus have been overlooked or not as highlighted today. Looking at art through this socio-economic lens really opens your eyes to different questions. Curator: Exactly. And it's important to continually ask those questions, interrogate those assumptions, and seek out the stories often left out of the dominant historical narrative. It reframes how we experience art and connect with its complex cultural resonance.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.