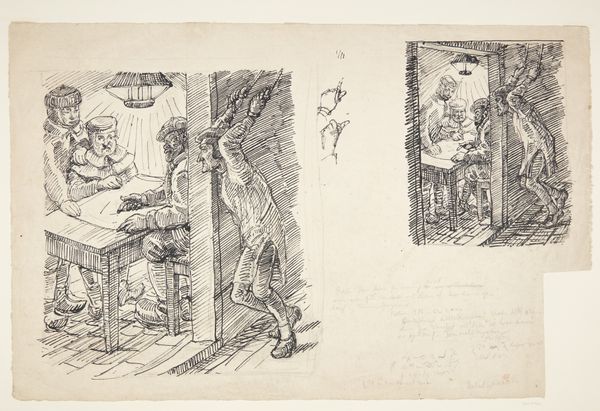

drawing, ink, pen

#

drawing

#

narrative-art

#

figuration

#

ink

#

pen-ink sketch

#

pen work

#

sketchbook drawing

#

pen

#

genre-painting

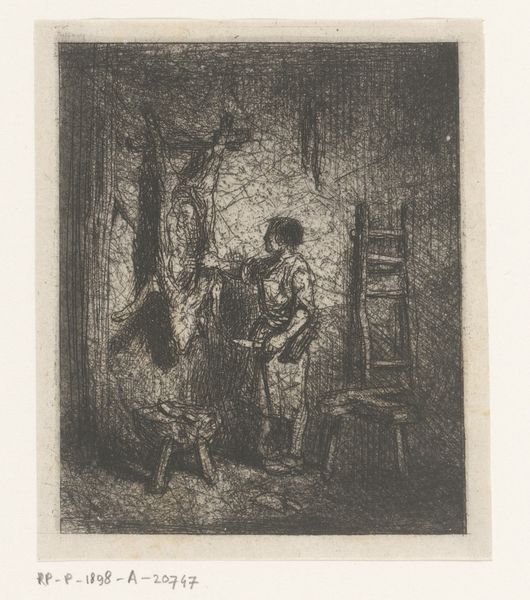

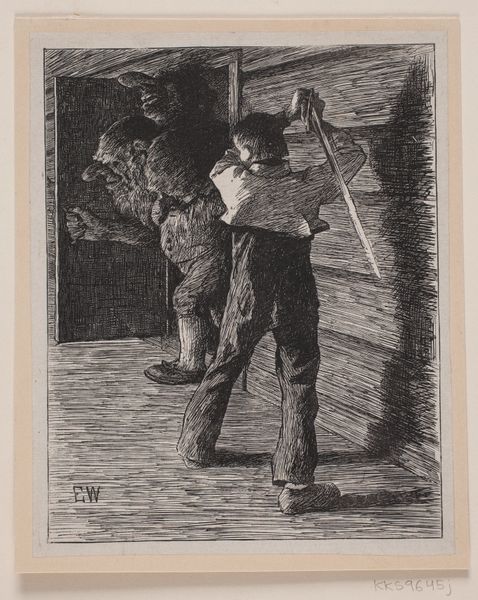

Dimensions: height 334 mm, width 294 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This pen-and-ink drawing, created by Willem Pothast between 1887 and 1916, is titled "Boy and Chained Man in a Workshop". Editor: The initial impact is one of stark contrast. The crisp lines create a grimy atmosphere, but the postures feel more like storytelling. A strange moment suspended. Curator: Pothast’s rendering of labor immediately triggers several trains of thought. What labor system are we viewing here? Is this bonded labor? And how does the presence of the young boy further implicate the man's unfreedom? Editor: Absolutely. My eye is drawn to the details – the boy’s clothing suggests a different class status, even authority, and it also strikes me how deliberately those chains have been rendered, the man’s gesture of open palms in his direction. The hammer resting near his feet serves as an important motif; suggesting themes of work, production, as well as oppression and violence. Curator: Indeed, the artist frames questions of power dynamics, particularly across class, through this tableau. Notice too, how the workshop, itself seems a character within this narrative of unfreedom; tools hanging rigidly on the wall – each perhaps emblematic of various coercive labors – juxtaposed against what appears as child’s innocence and, frankly, curiosity. How does Pothast then subtly ask, through form and imagery, what social norms or inequalities enable certain classes freedoms, and constrain others? Editor: Right, it speaks to cultural memory as well, maybe not as literally. Chains and hammers are symbols of struggle, constraint but also potential force. Is the child complicit or a future liberator? Curator: These historical and visual relationships, even within seemingly simple scenes, allow for critical interrogation. We can ask what narratives of industrialization and child labor were circulated through late 19th and early 20th-century genre paintings such as this; as well as if they contested or reinscribed certain historical conditions. Editor: And it reminds us how much symbolism, and by extension social commentary, is embedded even in casual-seeming compositions of the everyday. It’s about taking a deeper look beyond the surface image.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.