Dimensions: support: 1200 x 1200 mm frame: 1335 x 1338 x 100 mm

Copyright: © Tate | CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 DEED, Photo: Tate

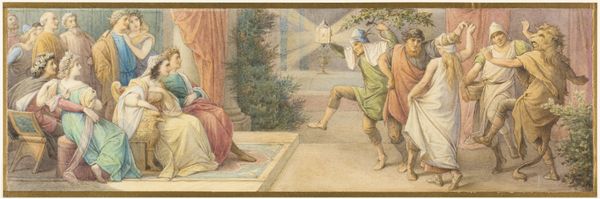

Editor: So, this is Duncan Grant’s *The Queen of Sheba*, currently at the Tate. I’m really struck by the contrast between the two figures. What can you tell me about this painting? Curator: Look closely at their gestures, their postures. How might Grant be using these visual cues to comment on power dynamics or societal roles within the narrative of the Queen of Sheba’s visit to Solomon? Editor: I hadn’t thought about it that way. It seems like they are both trapped by their positions. Curator: Exactly. Think about Grant's involvement with the Bloomsbury Group and their challenges to Victorian social norms. How might that context inform his interpretation of this biblical encounter? Editor: That’s such a different way to look at a familiar story! Curator: By understanding the historical and social context, we can start to see how Grant uses this familiar subject to explore his own contemporary concerns. Editor: I'll never see this painting the same way again.

Comments

tate 10 months ago

⋮

http://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/grant-the-queen-of-sheba-n03169

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.

tate 10 months ago

⋮

Grant painted this in the spring of 1912 as part of an abortive decorative scheme for Newnham College, Cambridge. His cousin, Pernel Strachey, had been a student there and later became its Principal. Grant based the Queen of Sheba on Pernel Strachey, and King Solomon upon her brother, Grant’s great friend the writer Lytton Strachey. Lytton had a long square-cut auburn beard at this time, and Grant gives this physical attribute to King Solomon. Diaghilev’s Russian Ballet had been giving performances in London and Grant’s costumes probably owe a debt to this Russian influence. Also Karl Goldmark’s opera The Queen of Sheba was premièred in London in the winter of 1911. Gallery label, February 2010