weaving, textile

#

medieval

#

weaving

#

textile

#

figuration

#

oil painting

#

genre-painting

#

history-painting

#

international-gothic

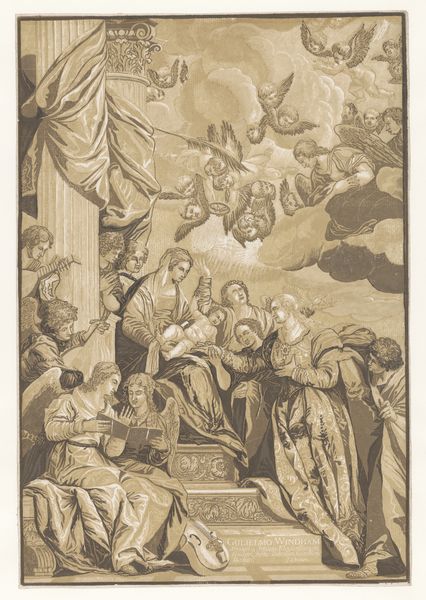

Dimensions: height 198.5 cm, width 136 cm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

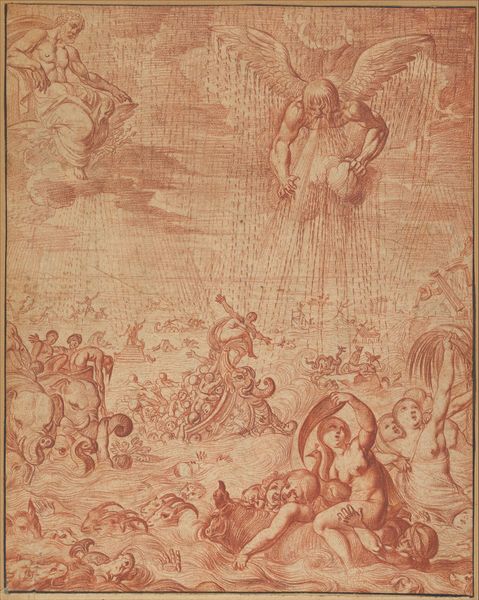

Curator: What a fascinating work. We’re looking at "The Birth of the Virgin Mary," a weaving, dating from around 1530, currently held here at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: It has a striking quality, this piece! My immediate reaction is that it’s visually busy, with a slightly muted palette, though that could just be its age. There's so much happening! Curator: Yes, there is! What’s captivating here, apart from its subject, is considering this tapestry as an object of production. It wasn't painted; it was woven, stitch by stitch. Think of the sheer labor, the countless hours. How did that production, that weaving, reinforce community and skill sharing? Who made these objects, and what were the socioeconomic conditions of their labor? Editor: That’s vital to consider. When I look at it through a contemporary lens, I’m struck by the depiction of women in particular. You see women supporting each other, attending to Mary. This setting, removed from the traditionally male spaces of power, highlights the unique social dynamics among women in that era. It’s interesting that so much of her actual birth is shown. Curator: The choice of weaving itself speaks to something deeper. Weaving as craft existed often in a domestic, less celebrated sphere of artmaking. It’s not bronze or oil, typically associated with the traditionally trained male artists, academies, and hierarchies. What were the societal reasons behind this relegation? Editor: Absolutely. And it encourages us to explore issues surrounding gender, domesticity, and art. Where do we see these same inequalities today and how can we address and work for broader access to the materials, venues, and representation needed for underrepresented or emerging artists and communities? Curator: Looking at the labor involved helps understand its immense cultural value at the time and for today, and as this particular work now resides within museum collections like this. Editor: Yes, this really is a compelling artwork when you consider not just what it represents, but what it *does*, even centuries later, opening pathways of intersectional thinking and consideration.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.