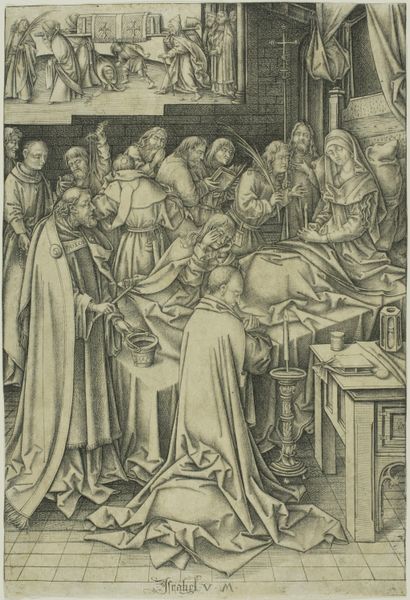

The Madonna with St. Anne, St. Catherine and St. Barbara 1490 - 1500

0:00

0:00

drawing, print, paper, engraving

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

medieval

#

germany

# print

#

figuration

#

paper

#

history-painting

#

northern-renaissance

#

engraving

Dimensions: 264 × 184 mm

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: The engraving before us, “The Madonna with St. Anne, St. Catherine and St. Barbara” by Israhel van Meckenem, dating from between 1490 and 1500, offers a glimpse into the religious art of the late medieval period in Germany. Editor: The immediate impression is of intricate layering; the eye dances across the many fine lines defining drapery and architectural details. It's all meticulously composed, but the effect borders on overwhelming, perhaps intentionally so. Curator: Absolutely, and let's not overlook the social context. Works like these were tools of didactic instruction for those largely excluded from literate culture. We see powerful female figures represented. Think of the implications regarding how these figures' actions intersect with gender roles and spiritual authority. Catherine, for instance, stands next to her spiked wheel as St. Barbara flanks her tower, their iconographies speaking to stories of immense resilience against patriarchal power. Editor: From a structural viewpoint, there's such tension created by the use of line. Notice how van Meckenem establishes a rigid architecture behind the figures, then contrasts it against the softly modeled forms and gently flowing drapery. This contrast adds dynamism but the print doesn't have areas of focus because everything seems to demand the same amount of the viewer's attention. Curator: This connects to issues of patronage and artistic agency at that moment in history. Was this van Meckenem's own articulation of the figures, or a visual program dictated from elsewhere? Looking deeper, it highlights power structures and challenges the established roles that governed life at that time. The choice to place women—saints and the Madonna—at the composition’s heart offers agency. Editor: Focusing solely on the visual components of the engraving, one can easily understand why this composition would appeal to the contemporary sensibility. The use of symmetry, curvilinear form, detailed attention, and rich figuration create a world that is at once familiar and aspirational. Curator: Considering this intersectional reading adds layers, moving us beyond pure aesthetics toward the dynamics of gender, faith, and resistance represented. What could such images mean for their viewership then, and now, concerning empowerment? Editor: I see your point, viewing art with intersectional dynamics enhances cultural understanding. For me, looking closely at its visual and technical language allows appreciation, too. Curator: Indeed, and perhaps understanding that formal language then unlocks avenues for contemporary viewers to forge a closer, more nuanced engagement.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.