#

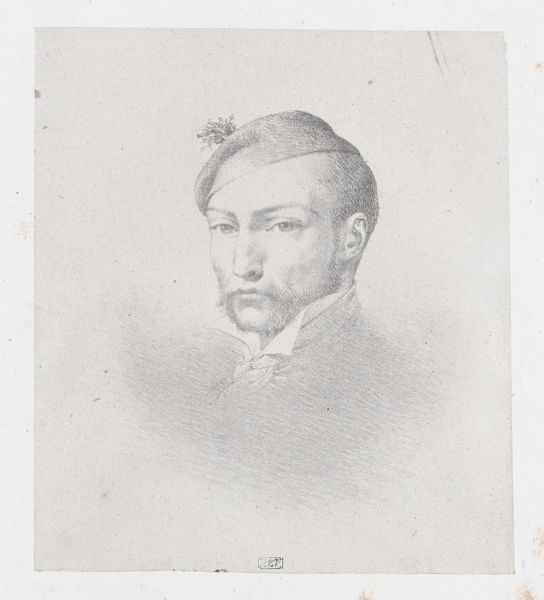

pencil drawn

#

aged paper

#

toned paper

#

light pencil work

#

pencil sketch

#

personal sketchbook

#

coloured pencil

#

19th century

#

watercolour illustration

#

watercolor

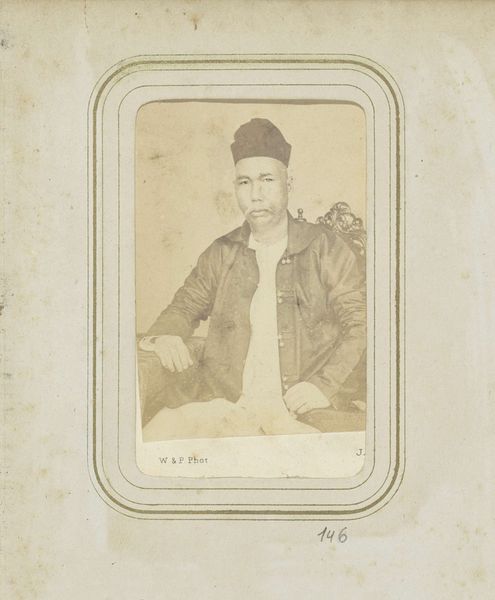

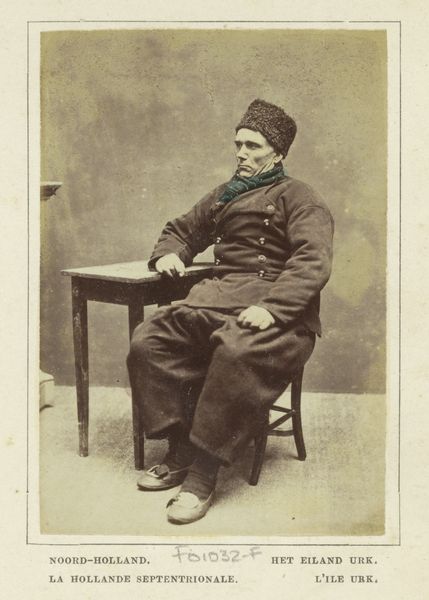

Dimensions: height 91 mm, width 58 mm, height 105 mm, width 63 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

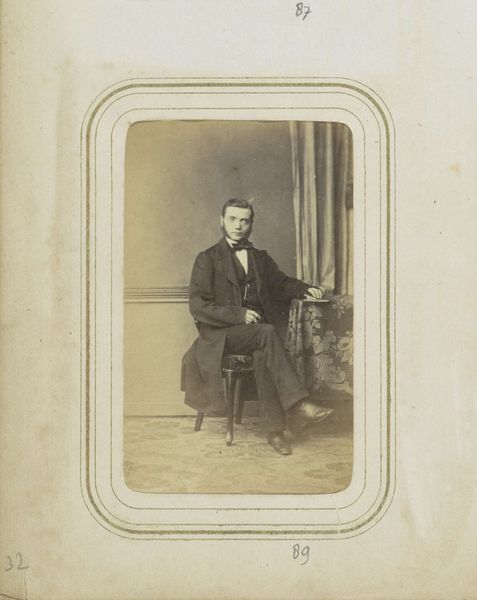

Curator: This piece, found here at the Rijksmuseum, is simply titled "Portret van een man in een jas met een hoofddeksel"—"Portrait of a Man in a Coat with a Headdress". It dates back to somewhere between 1857 and 1880. It's work by Woodbury & Page. Editor: The first thing that strikes me is the serenity in the sitter's expression; it's quite remarkable. The oval frame lends a sense of intimacy to the portrayal. What sort of context do we need to know for this particular subject? Curator: Well, in examining such portraits, we have to be hyper-aware of the dynamics inherent in colonial portraiture. The sitters rarely had control over their own image. It is crucial to think of the subject and ask what he was gaining or losing in the encounter. What was the photographer gaining? Editor: The headdress and clothing immediately speak of cultural identity, signaling, perhaps, social status or religious affiliation. I see a conscious presentation of self, even within the confines you describe. The way the light falls, there's definitely an effort made to show this individual respectfully. Curator: Exactly, the very fact that the sitter is facing forward and engaging the viewer is really powerful. In this time period in this geographical context that act defies much Western art, particularly much contemporary art in Western countries where persons of color are not able to engage eye to eye with the presumed “viewer”. Editor: Absolutely. And the way that Woodbury & Page used photography; their process and perspective. Their cultural background would surely be the lens through which they create this art. Curator: Precisely! That period saw an explosion of photography used to perpetuate colonial narratives. But individuals resist. And even, perhaps unconsciously, subvert. What does the fact of photographic preservation signify to the man depicted, a permanent mark. The implications for understanding personal versus historical visibility are rife here. Editor: Looking at it now through this lens, I agree; there are far deeper questions about agency and representation at play than one initially realizes. I really value what this work has helped reveal. Curator: For me, this portrait embodies a reminder that we have to always strive to remember that in art historical work representation and control are forever connected.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.