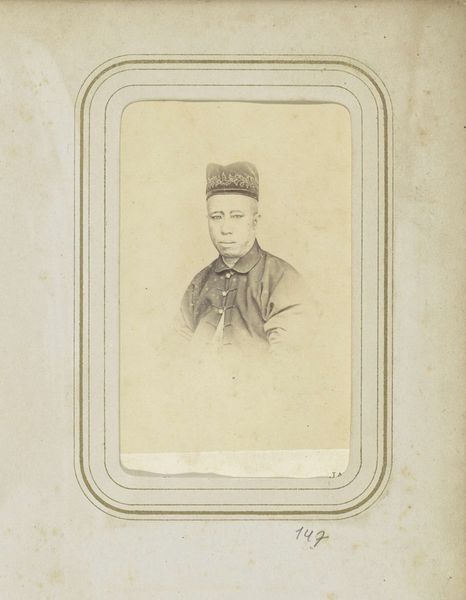

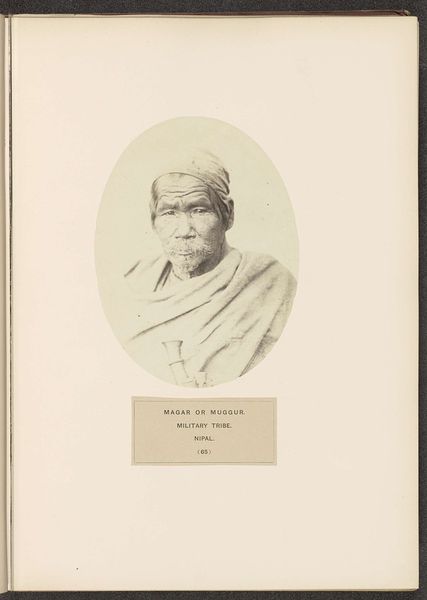

Dimensions: height 91 mm, width 58 mm, height 105 mm, width 63 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

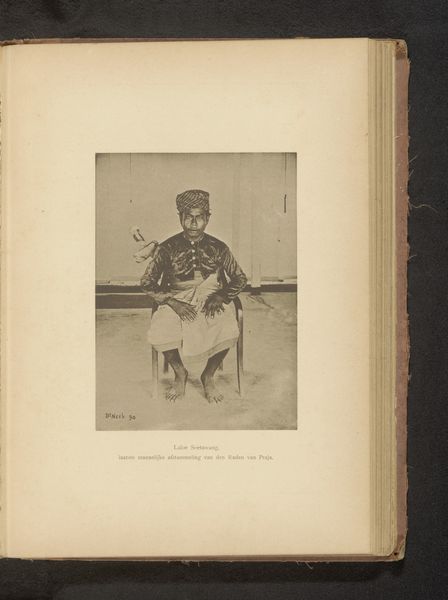

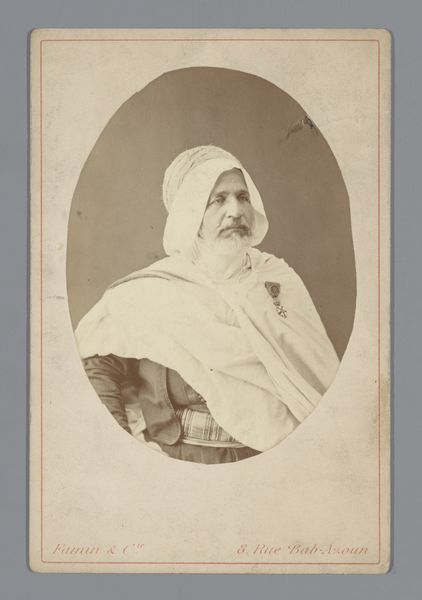

Curator: This photograph, entitled "Portret van een man in een jas met een hoofddeksel", translating to "Portrait of a Man in a Jacket with a Headdress", was created between 1857 and 1880 by Woodbury & Page. It's an albumen print. What's your first impression? Editor: The sepia tones give it a melancholic air, almost like looking at a memory fading. You can practically feel the texture of his clothing and the aged paper itself. How would they even achieve this effect? Curator: Albumen printing was quite popular during that period. They used egg whites to bind the photographic chemicals to the paper, creating a smooth surface that captures a great level of detail. We can assume it’s Pictorialism from the staging. Editor: Egg whites! Imagine the sheer quantity required, the labor of separating them. The process also must have contributed to the photograph’s tone. It reminds me of the laborious, very involved guild practices. It has that sense of quality to it. Curator: The man's gaze draws me in, too. It carries an intensity that speaks volumes, perhaps even reflects the colonial gaze and the representation of identity during that period. It would be useful to study his dress, the jacket, the head covering, to understand his social standing and role at that time. Editor: His clothing hints at a merging of cultures – that cap, that jacket – objects possibly sourced and manufactured along multiple trajectories. What were the social contexts for making photography at this time? Curator: Portraiture photography was a sign of status. A means for families, and for individuals to inscribe themselves in a social history. The ability to have your image preserved and reproduced conferred an influence within a social hierarchy. And as photography developed as an industry, a demand to define oneself arose in colonial populations as well. Editor: The material conditions of production—the print, the paper, the chemicals—all become traces of complex power relations, trade, and cultural exchanges during this era. Curator: Indeed. Considering how visual symbols create, maintain, and disrupt historical legacies, the portrait opens many such avenues to explore those exchanges. Editor: Seeing how an object, like this photograph, can tell so many material and cultural stories is just endlessly fascinating to me.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.