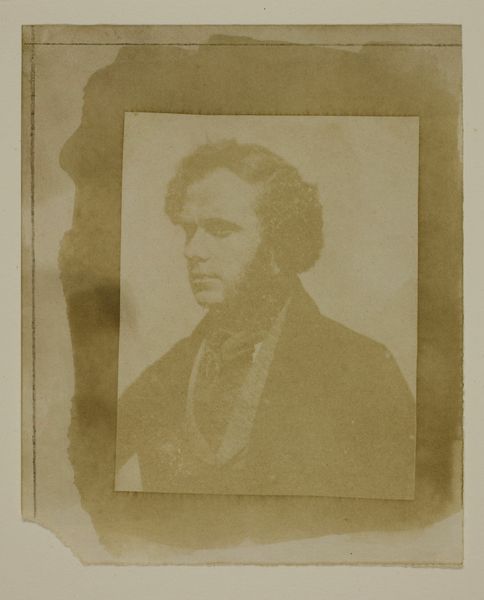

daguerreotype, photography

#

portrait

#

print photography

#

daguerreotype

#

photography

#

romanticism

#

men

#

portrait photography

#

profile

Copyright: Public Domain

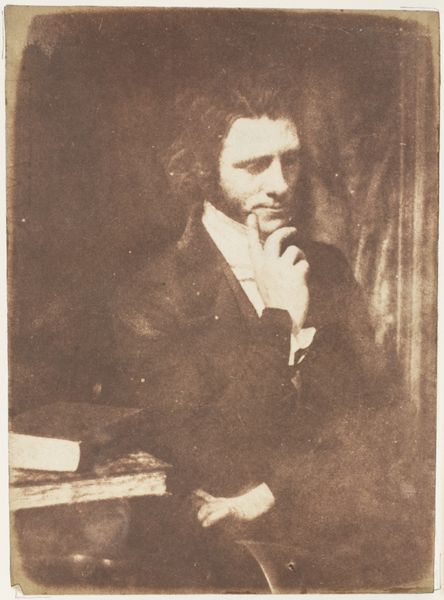

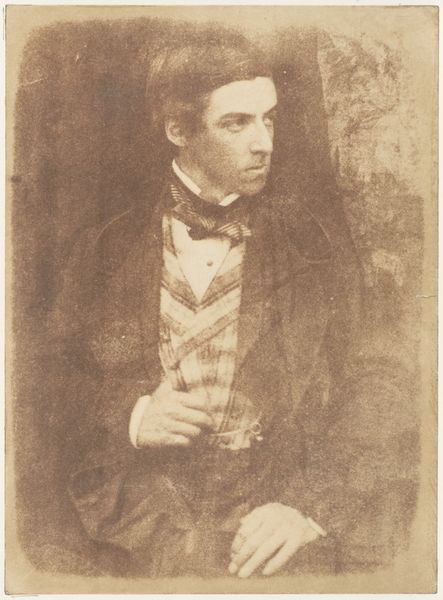

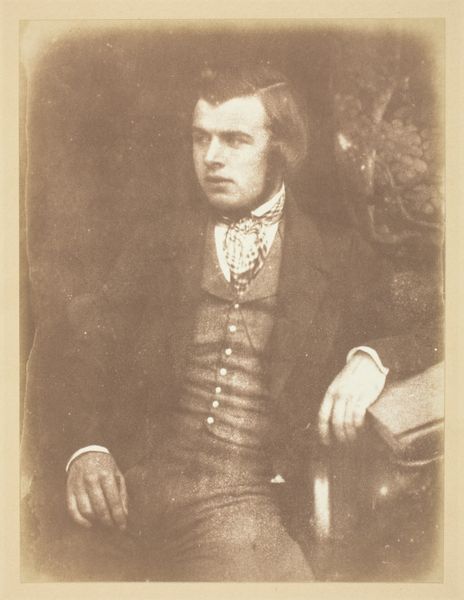

Editor: Here we have "Hugh Miller," a daguerreotype portrait from around 1843-1847 by Hill and Adamson. The image has this warm, sepia tone. I’m struck by how the softness of the image seems almost to counteract the sitter's stern expression. What's your take on this piece? Curator: I focus on the physical aspects of early photography to examine how this technology changes art production. Notice the surface of this daguerreotype – the silver-plated copper, meticulously polished, then chemically treated to capture the image. Think of the labor involved: the mining, refining, the careful handling of these materials, the posing of the sitter for extended periods. Does that shift your perception? Editor: Definitely! Knowing the painstaking process involved, I see the portrait not just as an image of a man, but as evidence of industrial and chemical processes brought into artistic creation. Curator: Exactly. Furthermore, consider the democratization of portraiture at the time. Photography offered a new way for a broader range of people to access representation. Who could now commission or sit for these images that previously were exclusive to those wealthy enough for painted portraits? How does the production change portraiture’s place within the art landscape? Editor: That's fascinating – this single image embodies a huge shift in access and artistic creation because of changing processes. It's more than just aesthetics; it's about the changing materials, technology, and labour that affect art and culture at a social level. Curator: Precisely. So much can be illuminated when we closely consider the making of art, alongside the economic and social forces at play.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.