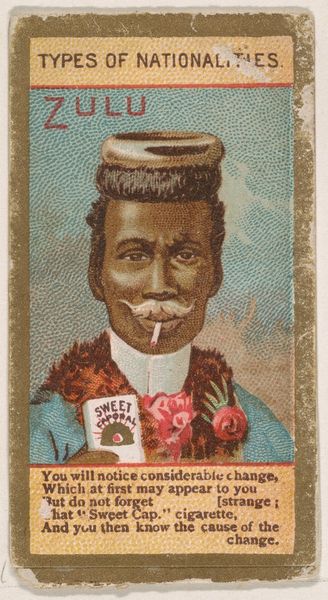

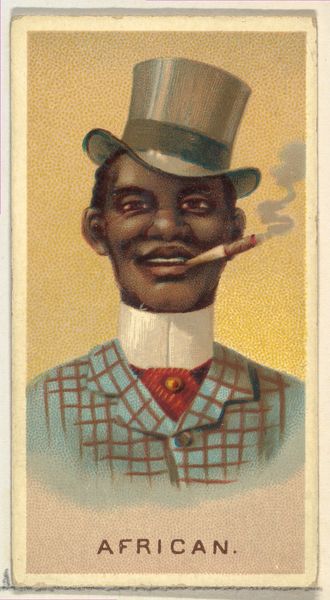

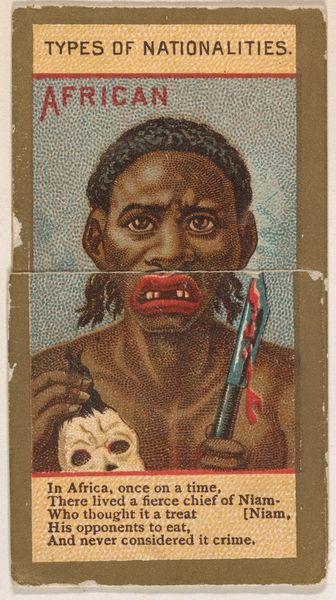

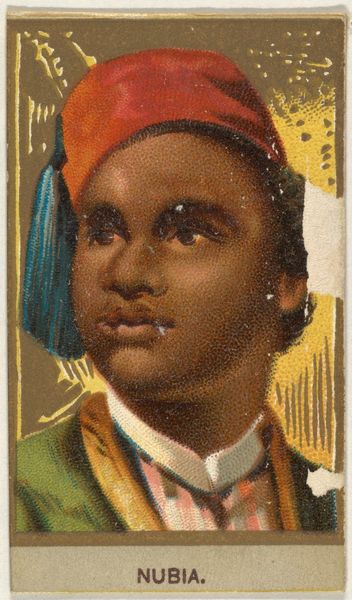

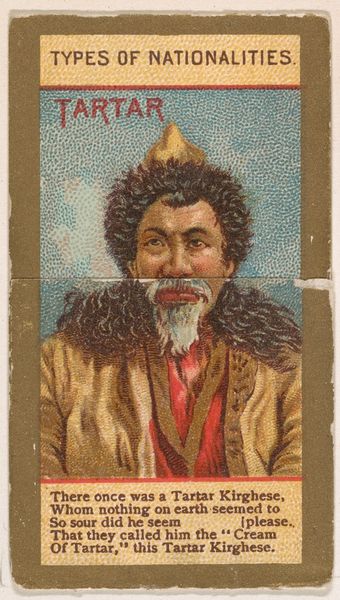

African, from Types of Nationalities (N240) issued by Kinney Bros. 1890

0:00

0:00

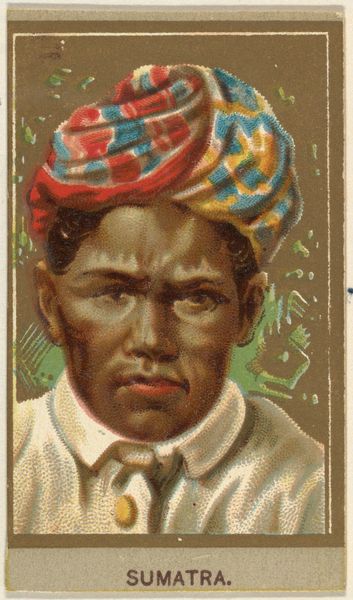

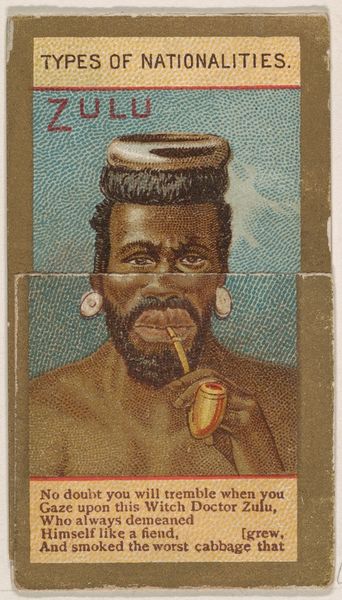

Dimensions: Sheet (Folded): 2 11/16 × 1 7/16 in. (6.8 × 3.7 cm) Sheet (Unfolded): 6 7/8 × 1 7/16 in. (17.4 × 3.7 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

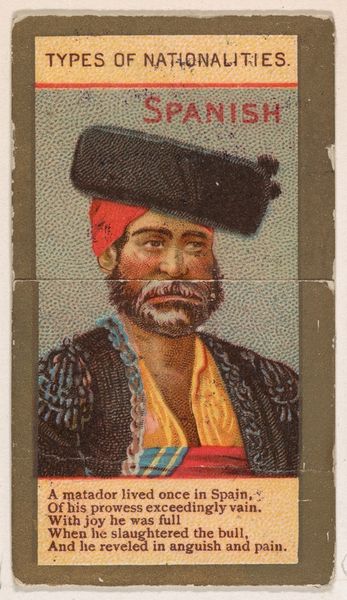

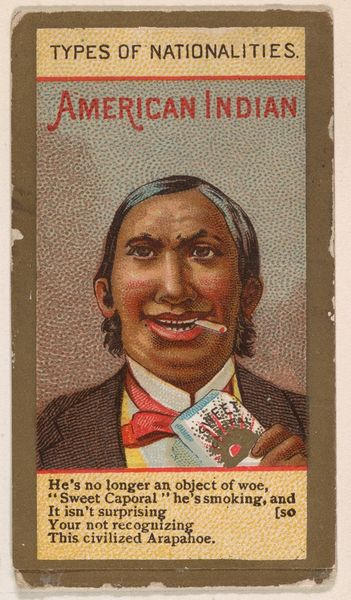

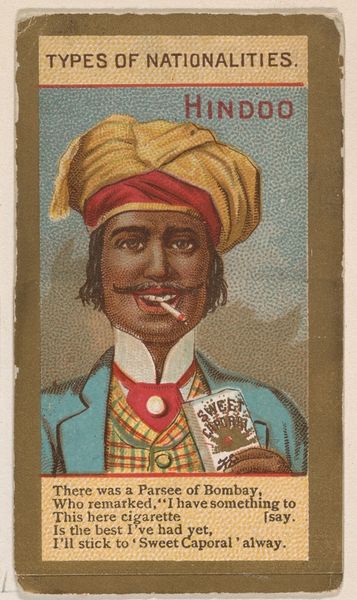

Curator: This peculiar piece is part of a series titled "Types of Nationalities," produced by Kinney Bros. around 1890. It's a coloured-pencil drawing, presented as a print, and housed right here at the Met. Editor: My first impression? It’s a really unsettling caricature. There’s a darkness beneath the colorful veneer; the over-the-top depiction is frankly, deeply troubling. Curator: Indeed. We have to confront the ugly truth of its historical context. This falls squarely within the realm of orientalism and the broader phenomenon of 19th-century caricature. The image, depicting an African man, comes from a time steeped in imperialist ideology, reinforcing harmful stereotypes for the sake of marketing tobacco. Editor: The text reinforces this point; lines like, "But he changed very much in his views, And he even was known to refuse to eat missionary – grew civilized; merry – ‘Sweet Corporal’ banished his blues." This isn't just a portrait; it’s a narrative, a claim about progress defined by colonial standards and "banished blues" sold alongside consumerism. This work perpetuates a highly problematic colonial fantasy, right? Curator: Absolutely. This image needs to be placed alongside considerations of power, racialization, and the construction of otherness during the height of European colonialism. Note the bow tie and brand of tobacco. Even though its material construction involves colored pencil and printed elements, its impact goes beyond aesthetics, speaking to how such visuals normalized racial biases and shaped popular perception. It actively participated in, and continues to be part of, the vocabulary of dehumanization. Editor: It's vital we contextualize these types of caricatures rather than dismiss them. Looking at them offers insight into the power dynamics that influenced so much art and imagery from that time, revealing the machinery behind those historical processes and power structures. This forces critical dialogue. Curator: Agreed. These images should encourage discourse surrounding how we can actively deconstruct those biases within ourselves. It’s essential we face the realities in images such as these, revealing how prejudice became entrenched. Editor: The legacy is potent. And maybe our discussion here provides an equally powerful response, highlighting these artworks with necessary nuance.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.