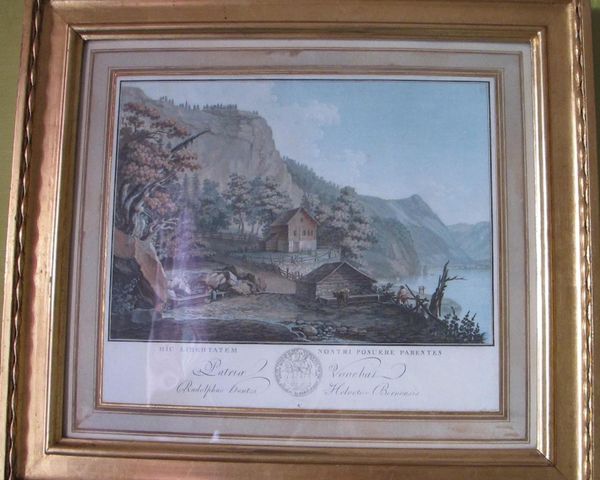

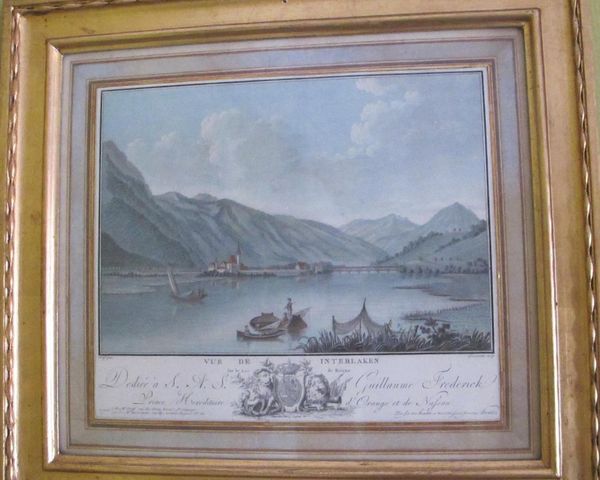

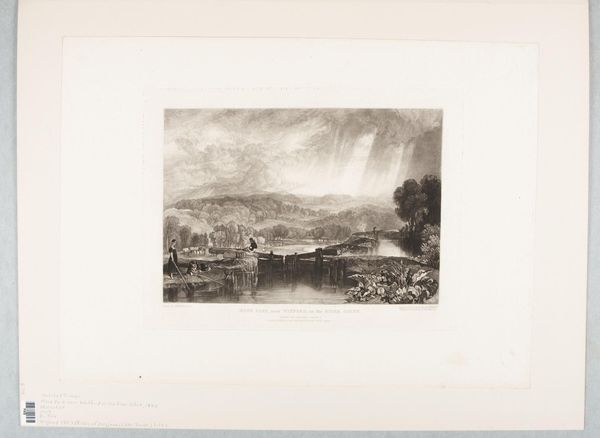

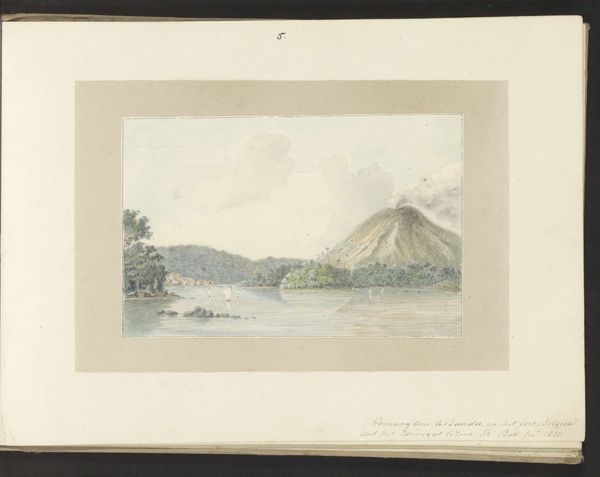

'Kerbo, fra vejen mellem Bragnæs og Christiania' 19th century

0:00

0:00

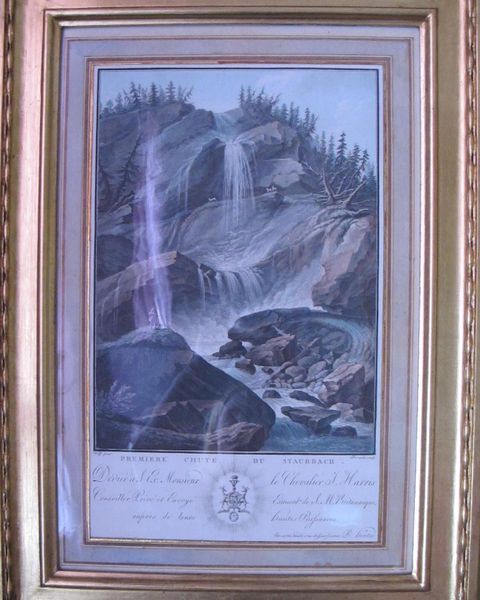

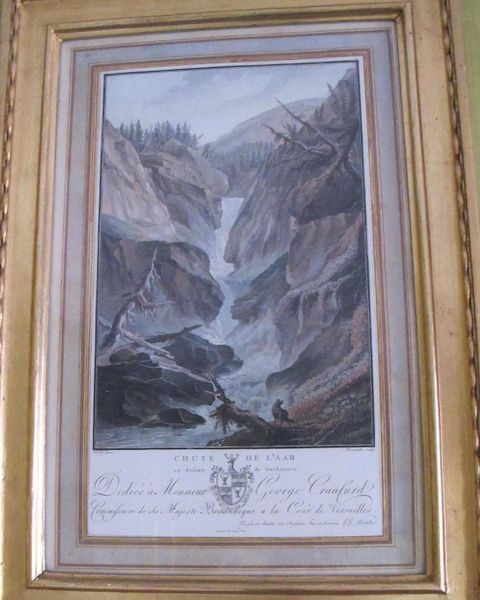

aquatint, print, watercolor

#

aquatint

#

water colours

# print

#

landscape

#

watercolor

#

romanticism

#

watercolor

Dimensions: 400 mm (height) x 510 mm (width) (None)

Curator: I find myself immediately drawn into the hushed atmosphere of this landscape. It feels both grand and intimately observed. What are your first impressions? Editor: This immediately strikes me as a scene bathed in the light of yearning. Look at the muted blues and greens. This speaks to Romanticism's focus on feeling and subjective experience, I’d say. It also speaks of the sublime – a kind of awe-inspiring power. Curator: Absolutely. The vista unfolding before us is "Kerbo, fra vejen mellem Bragnæs og Christiania," translating to 'Kerbo, from the road between Bragnæs and Christiania'. The artist, Heinrich Grosch, captures a specific place and, through it, an atmosphere. It's a print, created in the 19th century using watercolor and aquatint. Editor: Kerbo – place names can be magical incantations. Aquatint is interesting – it creates subtle tonal gradations – like seeing things through a veil of memory. How the artist has deployed it really softens the picture's symbolic load – all those Romantic era pine trees can get rather heavy-handed if you’re not careful. Curator: A light touch is definitely at play here. Consider how he renders the mountains in the background: their presence is more suggested than definitively stated. It’s less about topographic accuracy and more about conveying a mood – a kind of melancholic contemplation. What I find really compelling is the tension between the detailed foreground and the ethereal distance. Editor: Indeed. Notice too how tiny human presence is: A solitary boat upon the water, some buildings tucked amongst the trees. All signs point to nature, that immense theater, swallowing everything whole. What about the placement of light here, I am thinking in terms of consciousness and awareness of the viewer? It feels deliberately chosen… Curator: Perhaps pointing us toward our place in the landscape – to consider our own transience, the brevity of our mark upon the world. But in the detail he also suggests endurance. The work then isn't solely melancholic, but deeply contemplative. Editor: Contemplative—exactly. We are brought back to memory and place, how one's existence is entwined with the grand sweep of all things, how feelings emerge and coalesce – until we are face-to-face with awe. This journey is a perfect example of Romantic era, and the landscape's emotional and symbolic significance is what lingers now, in the quiet aftermath of seeing.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.