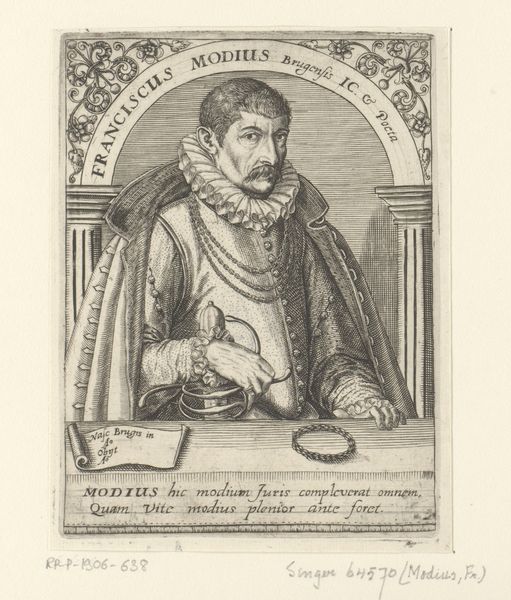

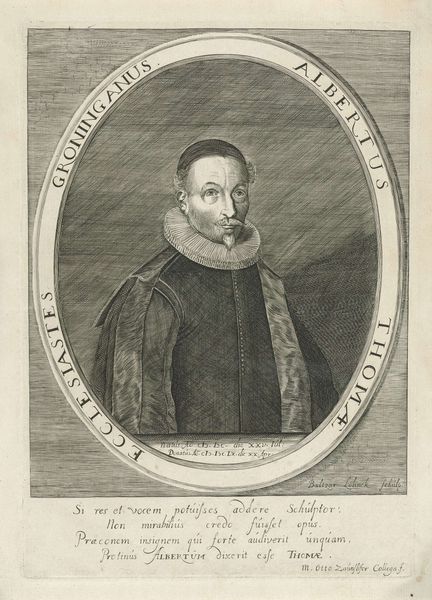

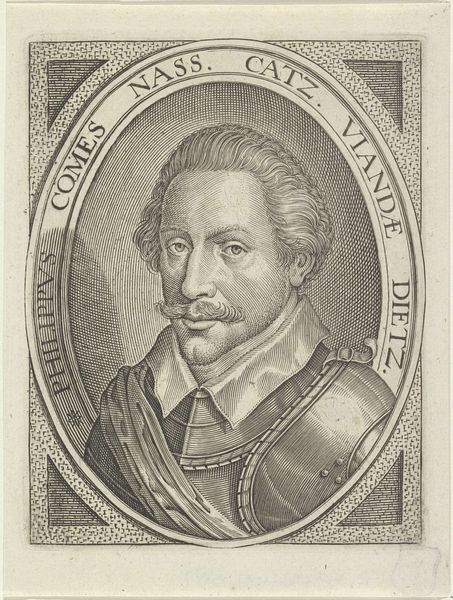

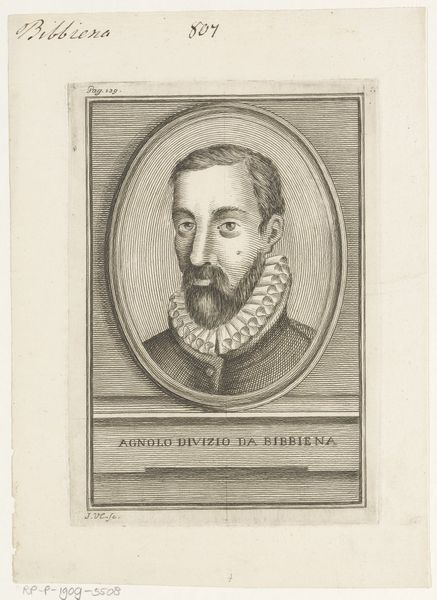

print, engraving

#

portrait

# print

#

mannerism

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 164 mm, width 112 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: This is "Portret van Marco Bragadino," a 1591 engraving by Dominicus Custos, currently held at the Rijksmuseum. I'm struck by the formality of the portrait, almost as if it's a mask someone is wearing. What can you tell me about this work? Curator: This portrait offers a glimpse into the complexities of representing power and identity during the late Renaissance. Notice the intricate details of Bragadino’s clothing, his collar, and the precisely rendered facial features, all symbols of status and intellect intended to project an image of authority in a world increasingly defined by social and religious upheaval. How do you read the symbolism in relation to the Latin inscriptions around the image? Editor: I hadn't considered that! It seems those phrases act as claims or perhaps subtle commentaries on his character... Did the print serve a political purpose, considering that portraits at that time were key propaganda tools? Curator: Absolutely. Prints like these circulated widely and became essential tools for constructing and disseminating reputations. Think about the political and religious climate of the late 16th century—the rise of print culture allowed for the strategic dissemination of images that served very specific ideological purposes. Bragadino is carefully positioned within this visual discourse. Consider also who Dominicus Custos and Joan ab Ach were and their roles in crafting this representation. How might their perspectives and affiliations shaped this portrayal? Editor: So it is a product of its time! I guess focusing only on the visual can lead one to oversee how much the social and historical frame impact the work. Thank you for your insights! Curator: Indeed. And by exploring that frame, we start to truly engage with the artwork as a document of cultural history and the forces at play at its moment of creation. It allows us to engage with these issues critically today.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.