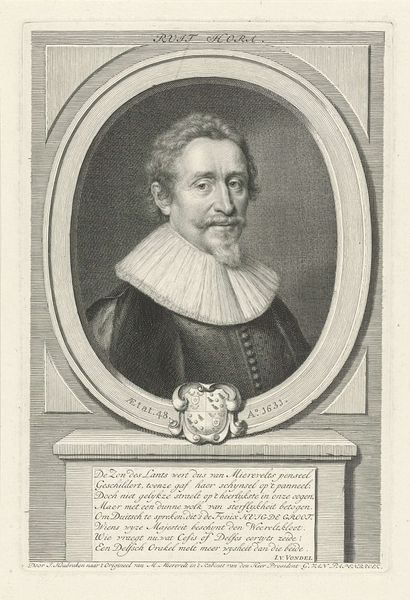

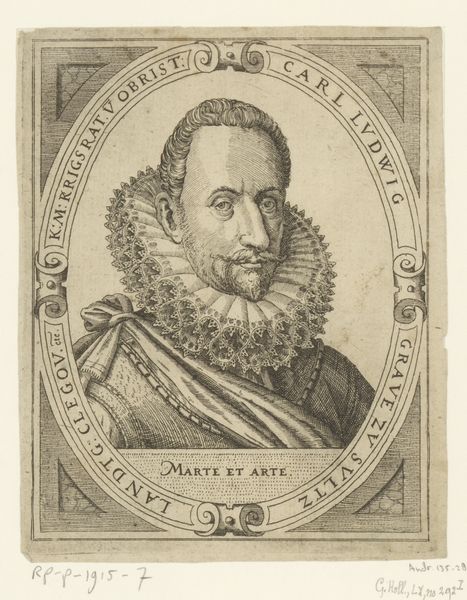

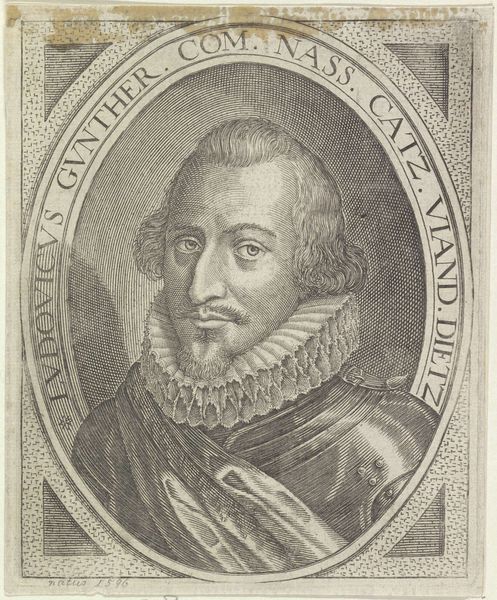

print, metal, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

# print

#

metal

#

old engraving style

#

caricature

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 172 mm, width 108 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Let's spend a moment reflecting on this portrayal of Willem I, Prince of Orange. This print, dating roughly between 1736 and 1775, is crafted in metal using an engraving technique by Jan Caspar Philips. What are your initial thoughts? Editor: I'm immediately struck by the intense gaze and how it situates the figure in a visual field of power and authority. His neck ruff appears to press against him; this might symbolize the constraints of leadership. There's almost a somber mood hanging over it. Curator: Indeed. His stare projects strength but is subtly tempered with something else, perhaps a hint of the burden of governance or the tumultuous times he lived in. The oval frame itself mimics classical portraiture, embedding him in a tradition of leadership and nobility, a continuity of power through symbolic form. The scene on the plinth below the portrait interests me, what do you read into this? Editor: To me, that seems less an act of heroism or statesmanship and more like the anxieties and realities of violence faced by Willem I in the late 16th century, in his battles against the Spanish Empire. Curator: Perhaps it represents a wider metaphor too, of conflict as integral to shaping national identity. It could function to situate the narrative of a singular, authoritative figure such as Prince Willem. But is that portrayal the whole story, or is it the legacy, the cultural memory and continuation that's most striking for a modern audience? Editor: That image functions ideologically by reaffirming hierarchical power, particularly male leadership, as natural and even heroic. Is there perhaps something of a tension there between honoring and deconstructing the symbolic work performed by such images, even prints like this one? How do we reconcile that legacy with contemporary demands for diverse and inclusive representation in positions of power? Curator: That push and pull—between respecting history and interrogating its underpinnings—is where the power lies for a contemporary audience, I think. What’s recorded on paper continues as cultural artifact long after it has been made. Editor: Ultimately, these are very complex representations, demanding our continued attention. Thank you.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.