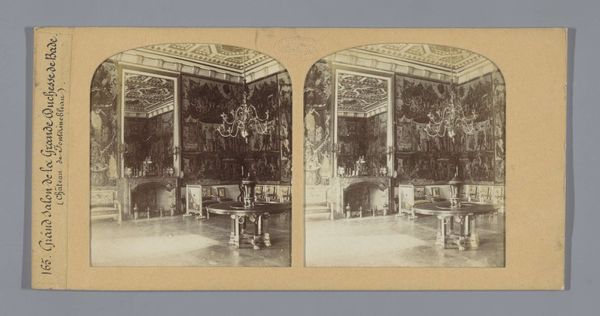

print, photography, albumen-print

# print

#

photography

#

cityscape

#

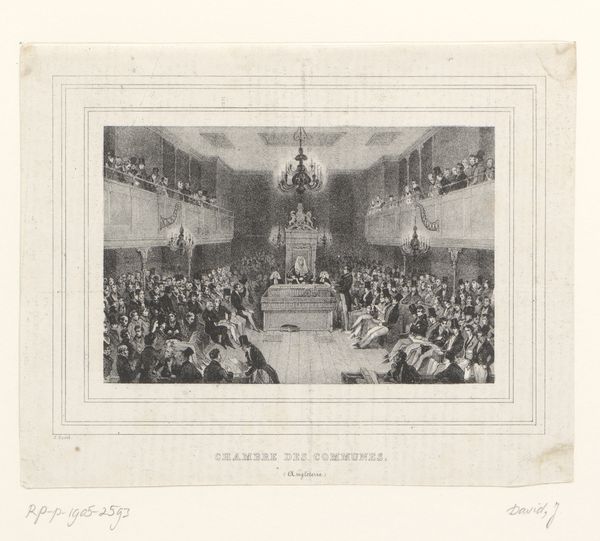

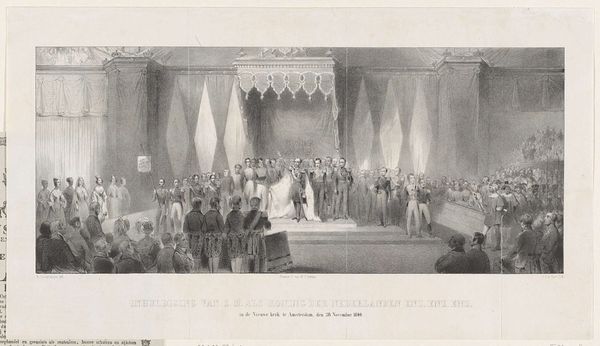

history-painting

#

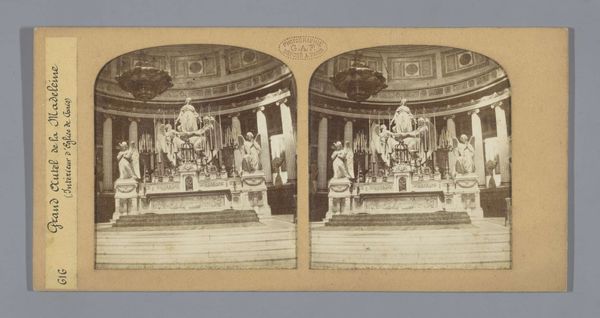

albumen-print

Dimensions: height 85 mm, width 170 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

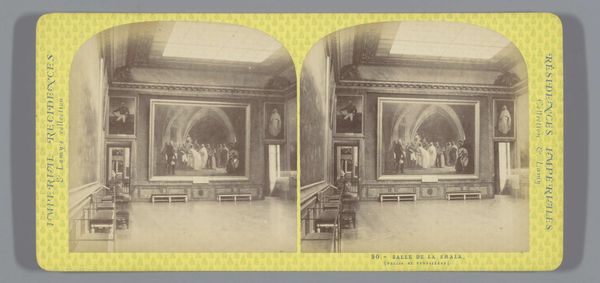

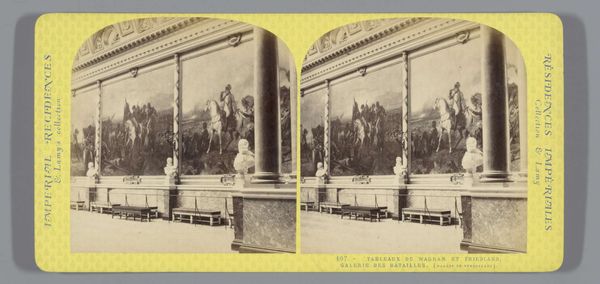

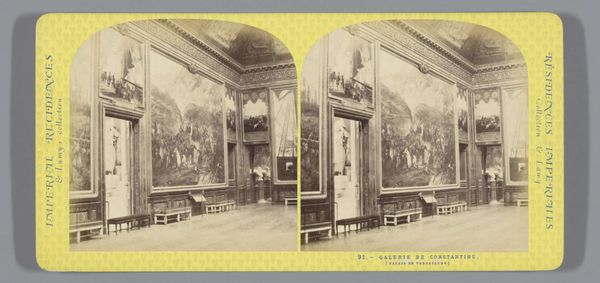

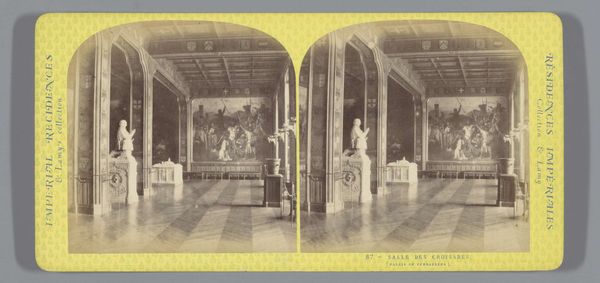

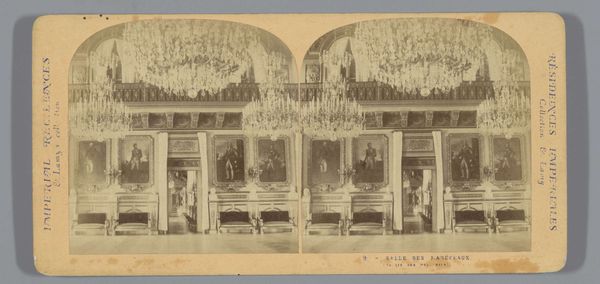

Curator: We’re looking at "Zaal met schilderijen in het paleis van Versailles," or "Room with paintings in the Palace of Versailles," an albumen print dating roughly from 1860 to 1880 by Ernest Eléonor Pierre Lamy. What's your first take? Editor: Impressive in its scale, certainly. The albumen print gives a beautiful sepia tone, highlighting the contrast between the grand murals and the simpler benches. It feels incredibly staged and curated, almost suffocating in its perfection. Curator: Right, the "staging" you're sensing reflects a specific desire in the mid-19th century to capture, and, importantly, distribute images of power. Lamy, through photography and printmaking, is participating in that industry. We're talking about industrial reproduction—the rise of a visual culture available to the masses. The means by which power visualizes itself is crucial here. Editor: Absolutely, and who is this "masses?" This photograph served not only to inform them, but also to create a spectacle of power, reflecting France’s self-image during a tumultuous period. It represents a certain type of dominance, and it would be important to consider issues of class, labor, and exclusion during this period of social upheaval. Curator: Exactly. And consider albumen—thin layers of egg white that contribute to this warm tonality—as an innovative element in that process, not just an aesthetic choice. Lamy's selection of photography allows for a certain amount of dissemination but, ultimately, even at scale this represents luxury goods and culture at this moment in France. It begs us to consider what the subject *really* is when one photographs images of power—especially considering who they ultimately serve, or even exclude from their influence and control. Editor: The material processes of making history—interesting point. And how those technologies inevitably frame and distribute social memory and cultural belonging. In a period defined by rapid technological change and its own brand of identity politics, representations of rooms such as this were incredibly effective vehicles. The composition directs attention; it implies what it means to enter this place, but that also means one can not enter; one can be made to leave, based on a highly visible but carefully constructed social architecture. It feels critical to address the narrative this "albumen" version crafts with audiences who are aware of their relationship to empire and political legitimacy, as those considerations are as critical as photography in capturing how places like Versailles really worked. Curator: Well said, and those thoughts only reinforce my perspective as well. By delving into both the creation process and the era’s dynamics, our dialogue expands the historical implications and broadens perspectives about this representation. Editor: Precisely—highlighting the image's role and relevance within evolving cultural narratives allows an appreciation for both the subject matter and how the artistic object’s impact still has ramifications on issues of self and social structures to this day.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.