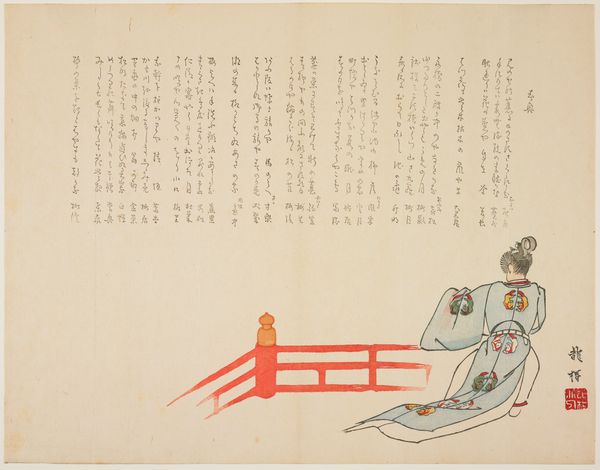

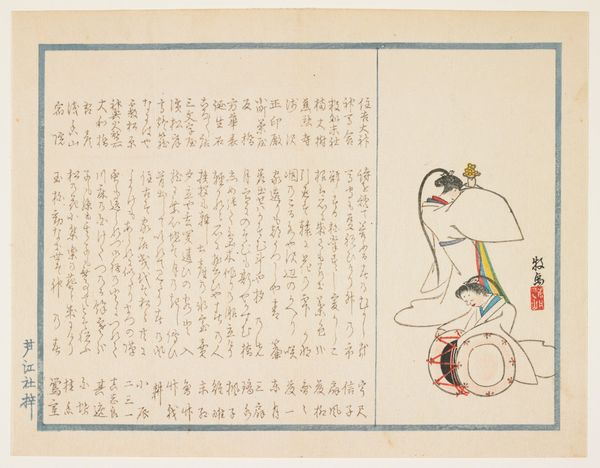

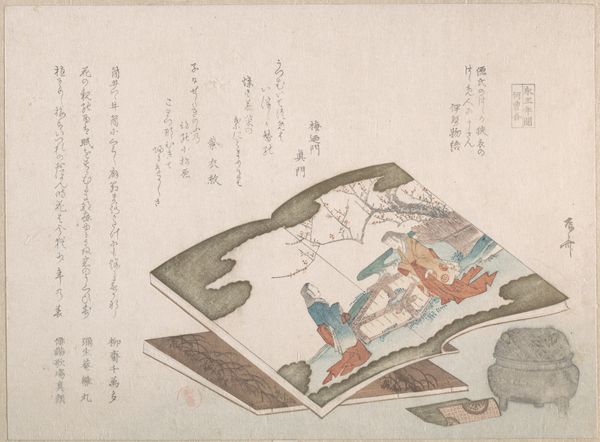

The Poetess Gishumon-in no Tango, from the series The Thirty-six Immortal Women Poets (Nishikizuri onna sanjurokkasen) Possibly 1615 - 1868

0:00

0:00

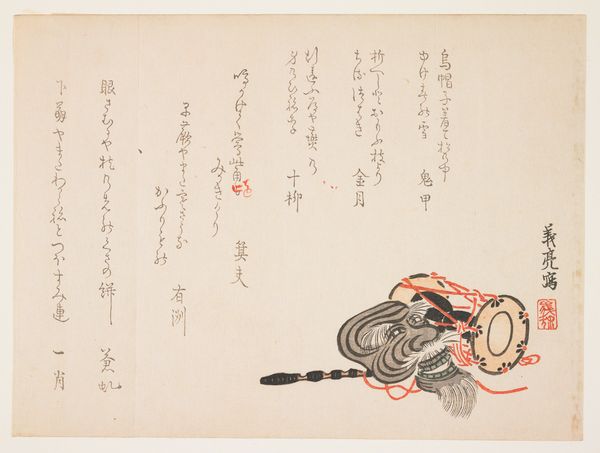

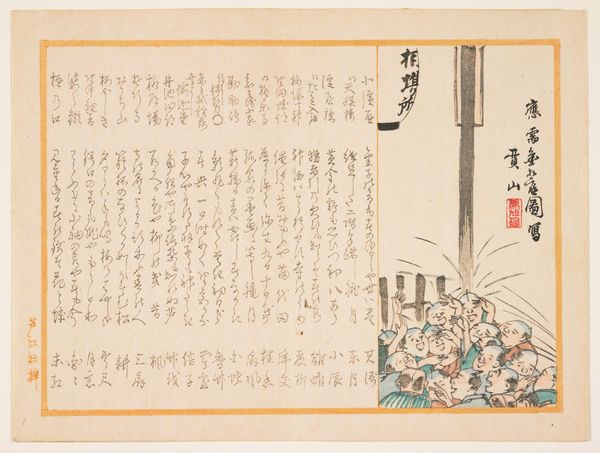

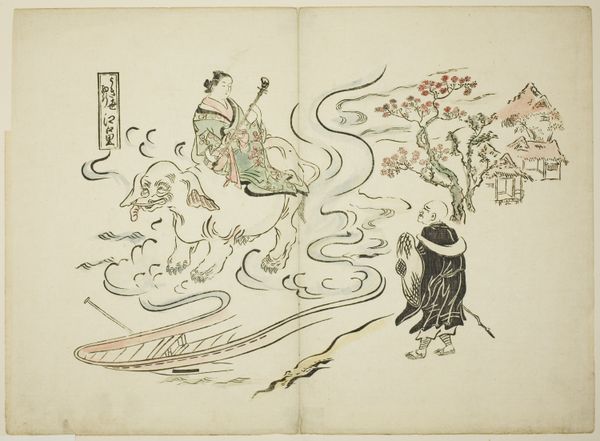

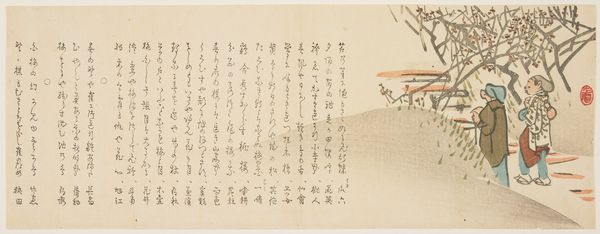

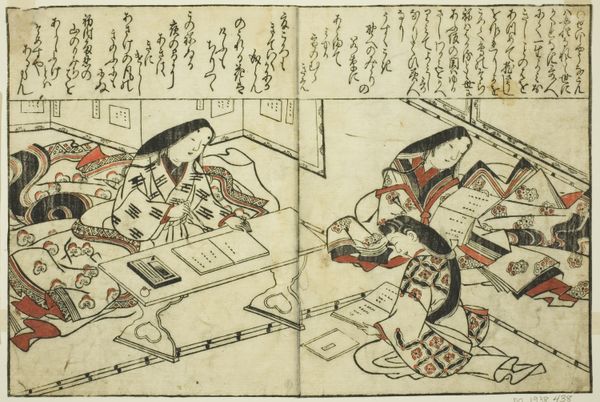

print, paper, ink, woodblock-print

#

portrait

#

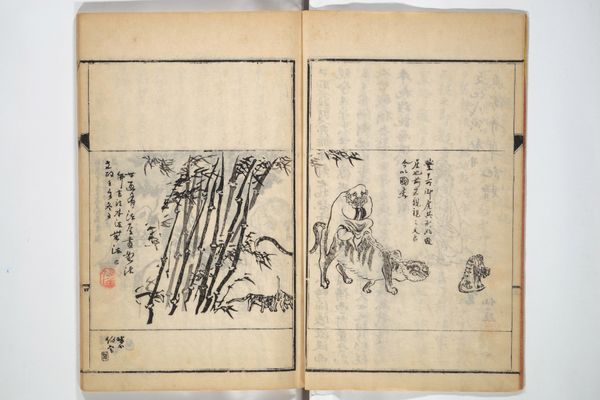

ink painting

# print

#

asian-art

#

ukiyo-e

#

figuration

#

paper

#

ink

#

woodblock-print

#

calligraphy

Dimensions: 24.7 × 18.5 cm (9 3/4 × 7 5/16 in.)

Copyright: Public Domain

Editor: This is "The Poetess Gishumon-in no Tango, from the series The Thirty-six Immortal Women Poets," a woodblock print in ink and color on paper by Chōbunsai Eishi. It dates, possibly, between 1615 and 1868. There's such detail in the rendering of her kimono... what can you tell me about it? Curator: It's fascinating to consider the means of production here. Ukiyo-e prints like this one involved a complex division of labor. We're not just seeing Eishi's design; we're seeing the skills of the woodblock carver and the printer. These artisans transformed the artist’s concept into a commodity, an object of consumption. How does that affect your interpretation? Editor: I hadn’t thought about the labor involved, just the artist’s vision. So, the intricate patterns weren't necessarily Eishi’s doing alone? Curator: Precisely. The choice of materials – the paper, the inks, the woodblocks – were determined not only by aesthetic considerations but also by availability, cost, and established workshop practices. This becomes a critical aspect of the art object itself. Look at the calligraphy; that required its own level of craftsmanship and tradition, didn't it? Editor: Yes, I see. So the social context, the workshop, and the materials are all inextricably linked. I was focusing solely on the subject of the poetess. Curator: It's a good starting point, but where do these materials come from? How were they processed? Who profited from their sale? These questions bring the unseen networks of production into view. Editor: That changes my view completely. I now see this print as less about the individual poetess and more as a product of a complex web of social and economic relationships. Curator: Exactly. By focusing on the materials and the means of production, we can uncover a richer understanding of the print’s historical and cultural significance. It goes beyond the surface representation to reveal the underlying structures of labor and consumption. Editor: Thank you; I learned so much by switching my perspective to materials and their place in the making of art. Curator: The best way to understand the making of art is often understanding its social contexts.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.