relief, public-art, sculpture, marble

#

public art

#

baroque

#

relief

#

public-art

#

sculpture

#

cityscape

#

history-painting

#

marble

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

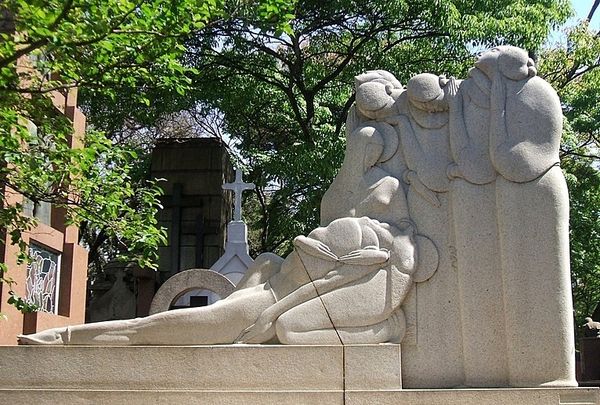

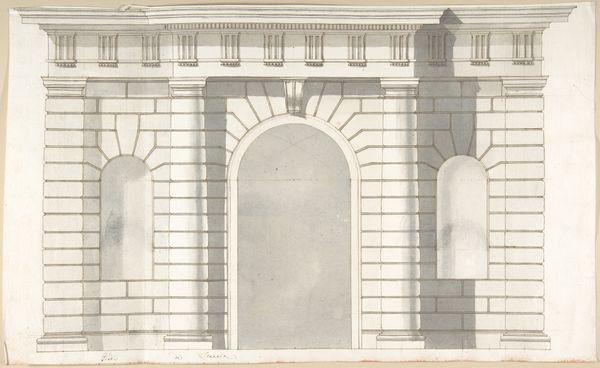

Editor: Here we have Hendrick Rusius' "Pediment," a marble relief sculpture from around 1654 or 1655. It has such a strong, almost regal presence. All that stone is just...imposing. I am wondering, what stands out to you about this piece? Curator: This "Pediment," it is true, carries itself with a grand air. What draws my eye are the fragmented narratives—these separate pieces that coalesce, hinting at stories deeply embedded in the cultural memory. Note the lions, for example. How do these regal symbols operate? What collective associations did they trigger for the original audience, and what traces of those associations persist today? Editor: That’s fascinating. So, the lions aren't *just* lions, they're symbolic representations of...power, maybe? Curator: Indeed. Power, courage, nobility. These animals act as visual shorthand, a language understood within a specific cultural framework. And the fragmented nature, almost archaeological, underscores how history is both revealed and obscured, demanding active interpretation. Consider the cityscape; what do you think its inclusion signifies? Editor: It's like they're deliberately presenting a history... but in pieces. The city almost feels secondary to the coat of arms and lions. Is the city being protected? Commemorated? Curator: Precisely! This piece invites speculation. The Rusius work isn't merely a decoration, but a container for cultural narratives. It seems to ask us what it truly means to represent not just physical space but also historical time through emblems. What will viewers in the future assume based on our civic and political monuments? Editor: I’ve never really thought about it that way. It’s amazing to think about what stories even these inanimate objects can hold, and the legacy they will leave.

Comments

rijksmuseum over 2 years ago

⋮

While one side of Regulierspoort showed the town’s old symbol (a cog ship), the other displayed its new coat of arms: three St Andrew’s crosses surmounted by an imperial crown and flanked by two lions. After his visit in 1488, Emperor Maximilian awarded the city the right to include the crown in its heraldic emblem, in gratitude for the warm reception he had received.

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.