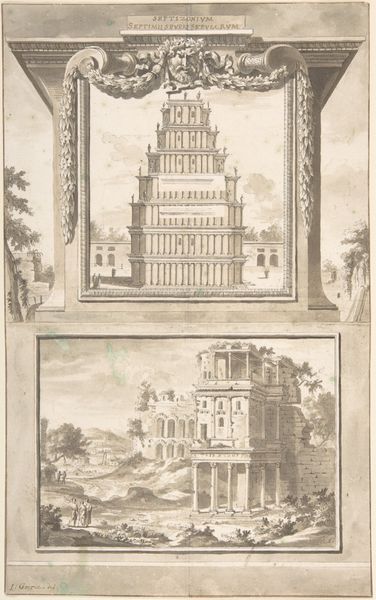

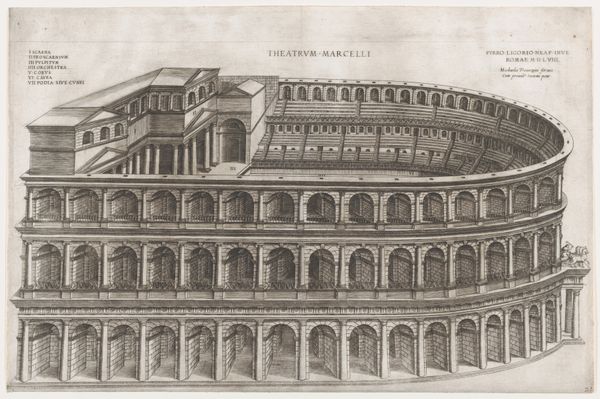

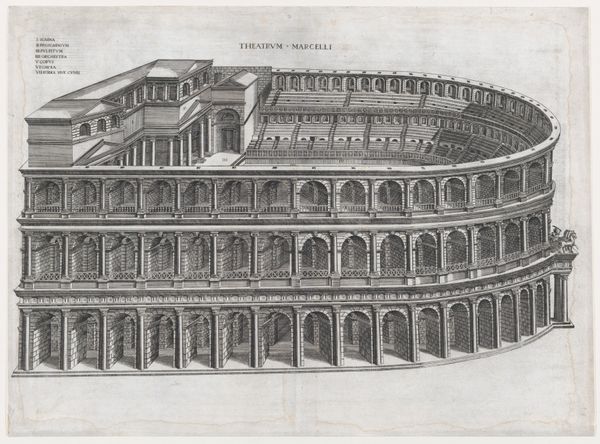

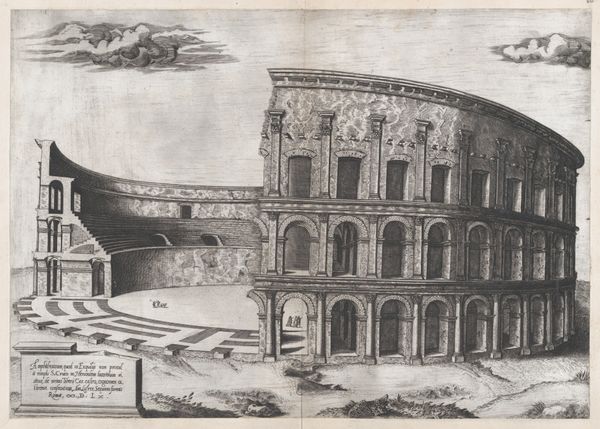

Reconstruction of the Theatre of Marcellus (above) and a View of the Ruins (below) 1690 - 1704

0:00

0:00

drawing, print, etching, architecture

#

drawing

# print

#

etching

#

pencil sketch

#

landscape

#

etching

#

romanesque

#

ancient-mediterranean

#

cityscape

#

architecture

Dimensions: Overall: 13 x 8 1/8in. (33 x 20.6cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Editor: This is Jan Goeree's "Reconstruction of the Theatre of Marcellus (above) and a View of the Ruins (below)," made between 1690 and 1704, a drawing and etching print currently residing at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. It presents a stark contrast, doesn't it? A pristine vision of what was, juxtaposed against the crumbling reality of what is. What sociopolitical implications might we draw from this dual presentation? Curator: Precisely! It's not merely an architectural study. Consider the act of reconstruction itself. Goeree isn't just showing us a building; he's offering a commentary on power, memory, and the ever-shifting landscape of identity. Why do you think societies are compelled to resurrect idealized versions of the past? What function does that serve for the present? Editor: I suppose it's a way of legitimizing current power structures, by grounding them in a glorious past. Is that a fair assessment in this case? Rome, after all, has always carried so much weight historically. Curator: Absolutely. Rome, in particular, represents a very potent symbol. The theater itself was a space of public gathering, a site of both entertainment and political discourse. By showcasing its reconstruction, Goeree could be subtly highlighting the desire for a return to a perceived golden age, but whose golden age was it? Whose voices were amplified, and whose were silenced within those walls? Editor: That's a great point. I hadn't considered the inherent inequalities within that idealized vision. Were all Romans truly represented within the theatre's performances and its politics? Curator: Exactly! We must question whose narratives are being privileged when we talk about reconstruction. It encourages us to deconstruct the very notion of a singular, unified past. To understand whose histories get erased or conveniently forgotten when we focus solely on the grandeur of "ancient" civilizations. It also serves to explore contemporary structures where cultural events take place, and assess whether their legacy could promote a truly accessible and inclusive platform. Editor: I never thought of it that way. It seems there's a lot more beneath the surface than just a simple before-and-after depiction. Thank you for pointing that out! Curator: Indeed. Art is always a conversation, an ongoing dialogue between the past, present, and future, and we're all invited to join in.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.