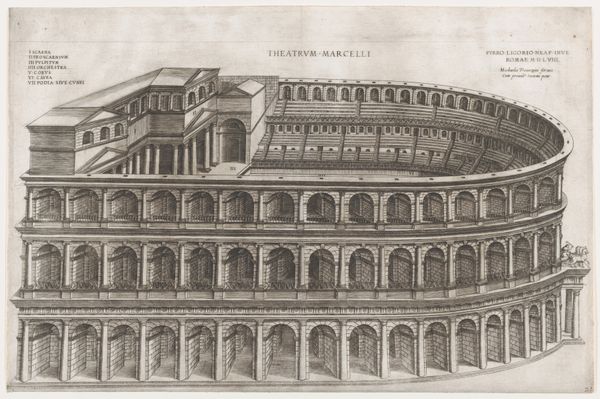

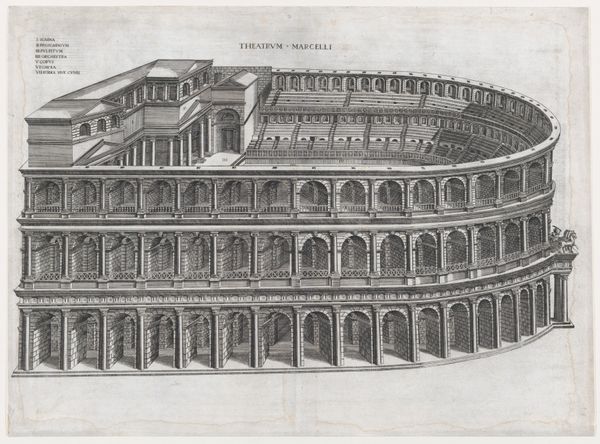

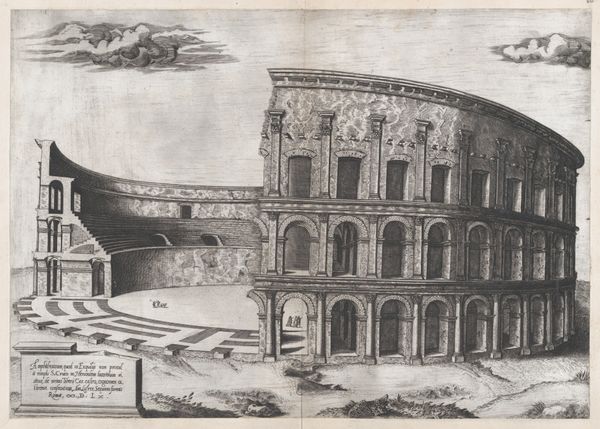

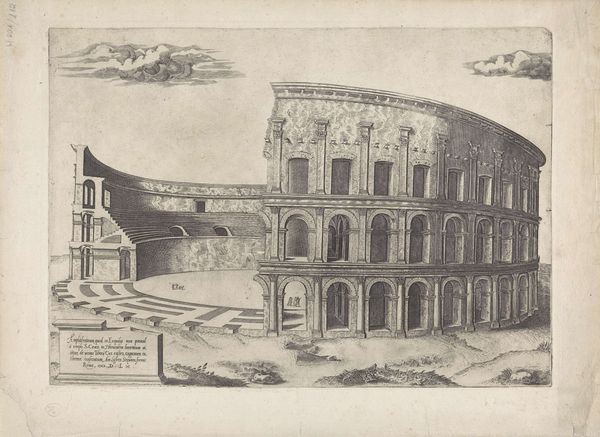

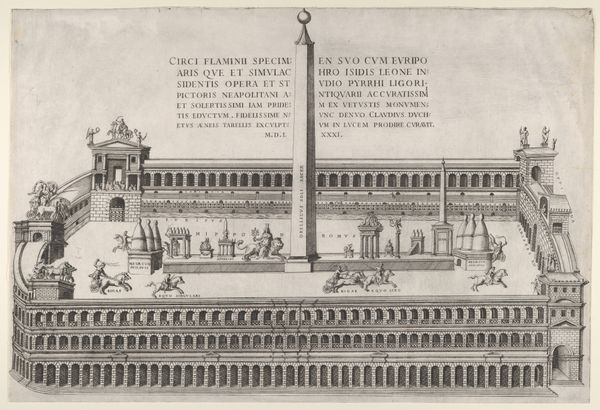

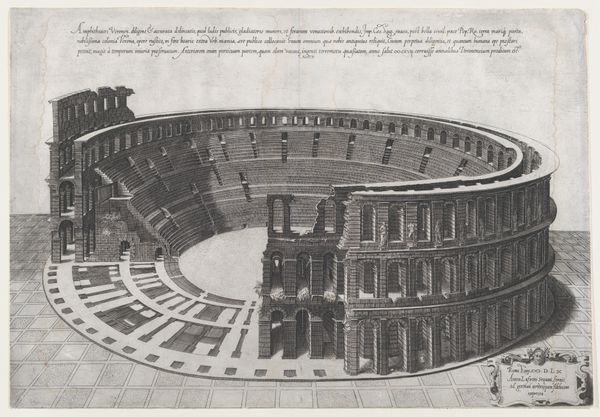

drawing, print, etching, engraving, architecture

#

drawing

#

neoclacissism

# print

#

etching

#

geometric

#

cityscape

#

engraving

#

architecture

Dimensions: 120 mm (height) x 183 mm (width) (bladmaal)

Curator: Immediately, I'm struck by its imposing architectural structure rendered so precisely, a real testament to the engraver's skill! Editor: Agreed, there's something deeply compelling about the detail. We're looking at Andreas Flint's "Theatrum," created sometime between 1767 and 1824, currently held at the SMK - Statens Museum for Kunst. It’s an etching, engraving, and print that depicts a cityscape...or more accurately, a theatrum, as the title indicates. Curator: Yes, and the material itself is so important. Think of the labour involved in creating such intricate lines, the process of etching, the physical act of making it is crucial to understanding the piece. And these types of prints were, in their time, fairly mass produced objects, not exclusive commodities for the wealthy but available to scholars, architects, and the burgeoning middle classes. Editor: Precisely. This piece is neoclassical, a movement rooted in recovering a supposed idealized past to serve political messages in its present. Notice the calculated geometry and rigid symmetry used to depict an ancient theatre – what underlying message of control, civic responsibility, and idealised power are we witnessing? Curator: Definitely a conscious effort to reflect classical ideals through reproducible formats such as engraving and etching. This print enabled access to architectural concepts on a grand scale. We get more people involved in material distribution when we question high-end commodification of visuality. It allows for different engagement forms through availability, doesn't it? Editor: Absolutely! By offering accessibility of an aesthetic experience to a broader populace, an artistic creation might initiate cultural engagement and activism through discussion and conversation; not limited to museums and academics. We can question the artwork within the cultural context and how neoclassical aesthetics served broader political narratives of power and social order. Curator: That element of questioning allows people to examine architectural constructs from their own perspective; to reflect on labor, tools, and accessible forms of distribution is vital to the discourse itself. To examine materiality is to enable inclusivity to cultural narratives that include marginalized populations often discarded from mainstream artistic representation. Editor: I couldn’t agree more. Seeing this through that lens opens so many avenues for discussing who had access to art, who controlled its narrative, and what role it played in reinforcing power structures. It challenges us to think critically about the function of art, both then and now. Curator: Indeed, moving away from aesthetic value as an untouchable idea, we encourage engagement beyond its intended creation, and in return offer voices not yet amplified. Editor: Thank you. Hopefully this approach enables each of our listeners to ask questions.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.