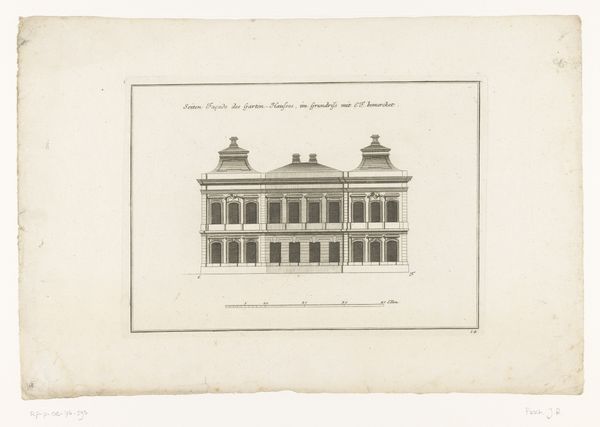

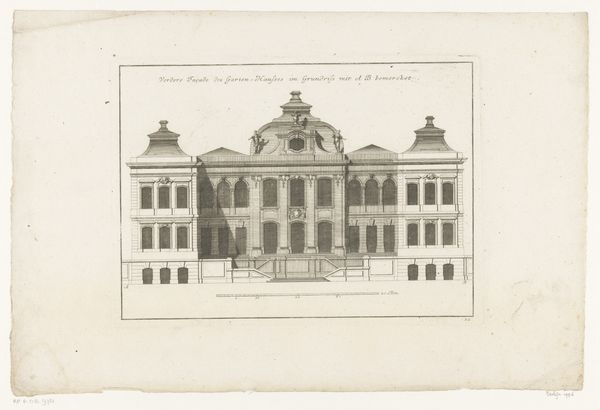

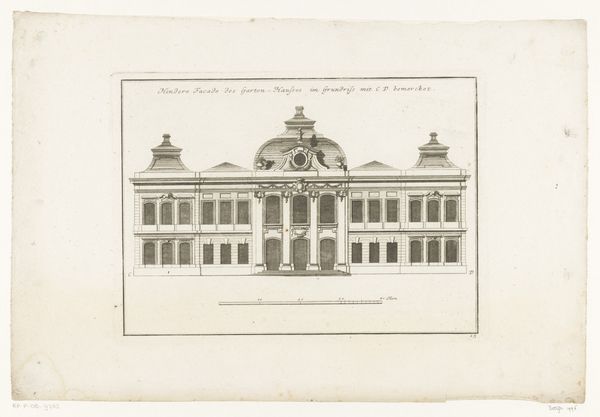

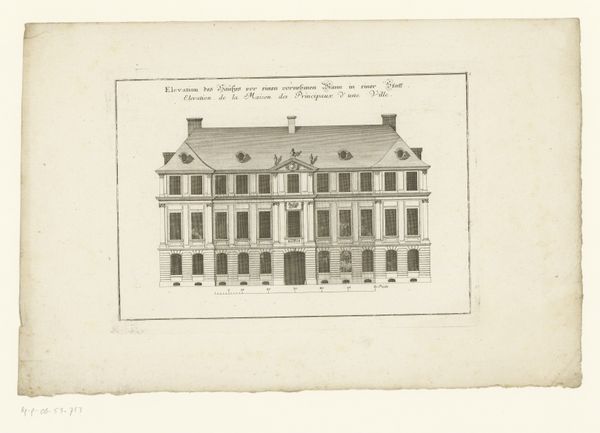

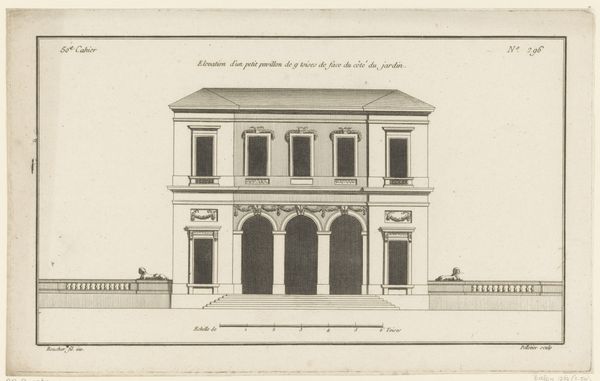

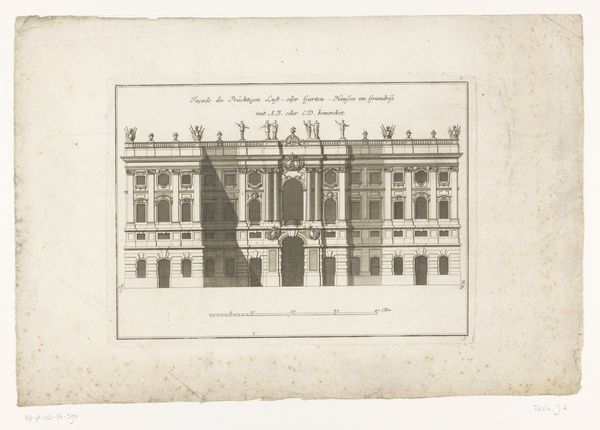

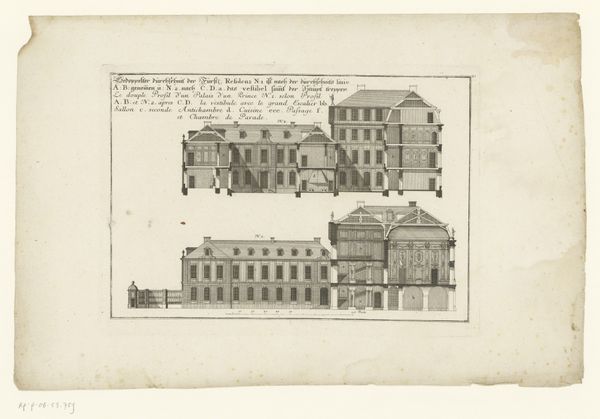

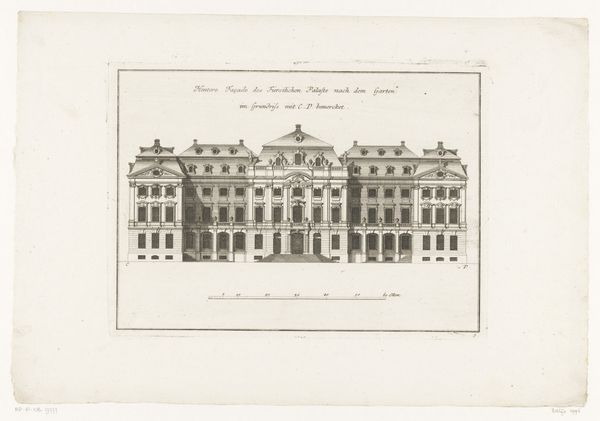

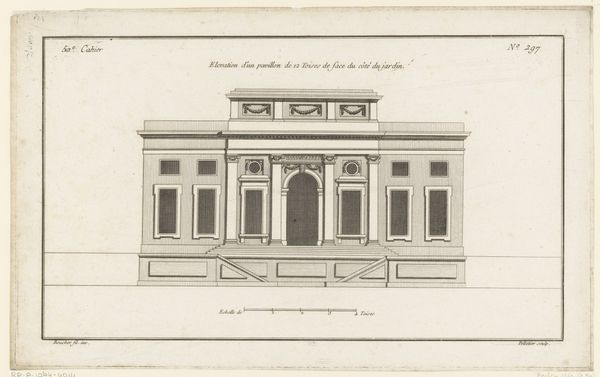

drawing, paper, ink, engraving, architecture

#

drawing

#

baroque

#

paper

#

ink

#

geometric

#

line

#

cityscape

#

engraving

#

architecture

Dimensions: height 219 mm, width 307 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Before us, we have "Dwarsdoorsnede van een tuinpaviljoen," an architectural drawing traced back to 1729. Crafted anonymously, it combines ink and engraving on paper to offer a precise look at a garden pavilion. What are your initial thoughts? Editor: It's stark, almost unsettlingly so. The lack of human presence, coupled with the cross-section view, feels clinical. I’m struck by how the architecture seems almost dissected, its innards laid bare. Curator: The drawing's medium serves a purpose. In the 18th century, drawings like these weren't meant for display but were vital for communicating design, showing structural elements, and facilitating discussion amongst builders and patrons. This period highly valued symmetry and order; how do you see that playing out? Editor: It’s performative! The clean lines and structured composition mask an underlying power dynamic. Gardens were tools for the elite to assert dominance and control. Curator: Absolutely. Gardens were not just aesthetic spaces, but stages where the powerful showcased wealth and taste, solidifying their position within the social hierarchy. Editor: And in this case, that stage is opened, dissected...The cross-section creates a sense of artificial transparency that speaks to surveillance and controlled vision. Even enjoyment becomes regulated! Curator: The Baroque style is evident here, and even in rendering a cross section you can see that theatricality shining through the design with ornate detailing in an era known for projecting strength and elegance. But I also feel a restraint, perhaps dictated by the functional purpose. Editor: Exactly. We see that tension echoed in debates around land ownership and access during that era. This carefully planned garden contrasts sharply with the lived experiences of those excluded from it, an era defined by enclosures and dispossession. Curator: Reflecting on this piece, I appreciate the peek into 18th-century architectural intent, showcasing how drawings were integral to creating these social spaces for the wealthy. Editor: And for me, it's a chilling reminder of how architecture embodies social power. Even a seemingly harmless garden pavilion can become a symbol of inequality.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.