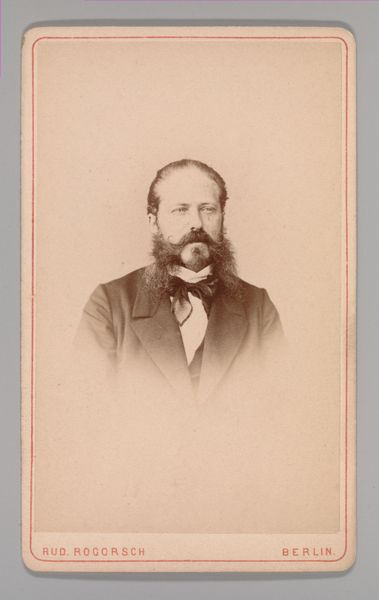

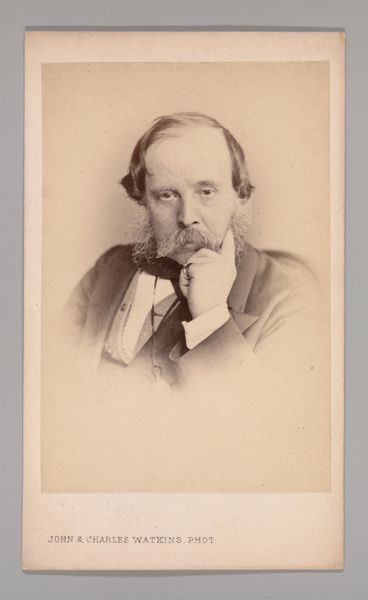

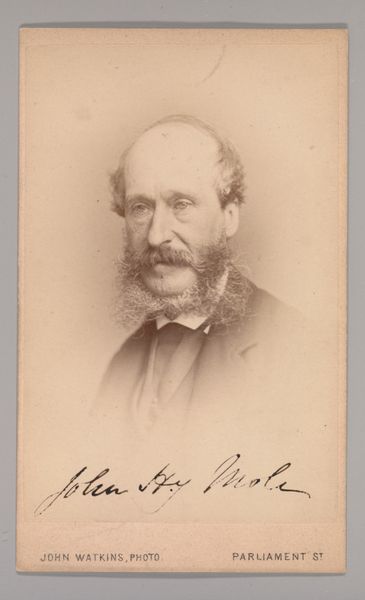

![[John Henry Mole] by John and Charles Watkins](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fd2w8kbdekdi1gv.cloudfront.net%2FeyJidWNrZXQiOiAiYXJ0ZXJhLWltYWdlcy1idWNrZXQiLCAia2V5IjogImFydHdvcmtzLzk3NzdkMjU3LTU5ZjQtNDhiZS05MWJlLWFlMmQzMGY2ZGY3OC85Nzc3ZDI1Ny01OWY0LTQ4YmUtOTFiZS1hZTJkMzBmNmRmNzhfZnVsbC5qcGciLCAiZWRpdHMiOiB7InJlc2l6ZSI6IHsid2lkdGgiOiAxOTIwLCAiaGVpZ2h0IjogMTkyMCwgImZpdCI6ICJpbnNpZGUifX19&w=3840&q=75)

print, photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

portrait

#

print photography

# print

#

photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

Dimensions: Approx. 10.2 x 6.3 cm (4 x 2 1/2 in.)

Copyright: Public Domain

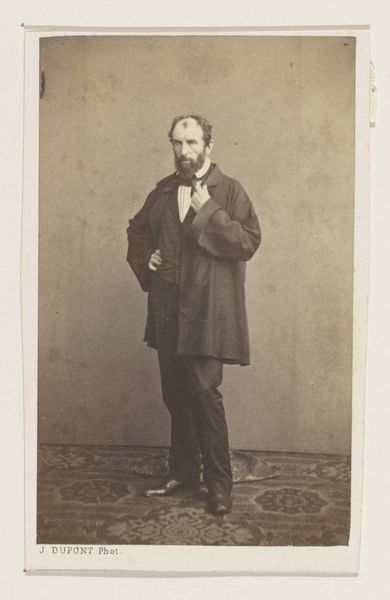

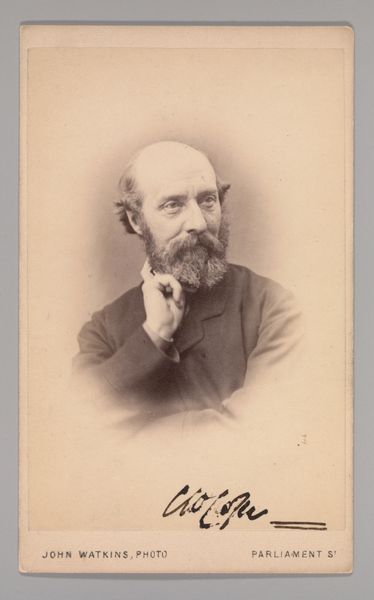

Curator: This gelatin silver print, created in the 1860s, is attributed to John and Charles Watkins. The subject, John Henry Mole, is presented in a classic portrait style, now housed at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. What is your first impression of the image? Editor: A kind of subdued elegance. The sepia tones lend it a melancholic air, almost like looking at a faded memory. His posture is relaxed, yet there's a pensiveness in his eyes and the way he rests his hand. It definitely speaks of a specific era and class. Curator: It’s fascinating how photographic portraits became essential tools in constructing social memory. In the 1860s, having your likeness captured signified a certain status, a deliberate effort to preserve one's presence in history, a conscious construction of legacy. Editor: Absolutely, and in considering the construction of identity, how might we examine Mole’s attire and posture as communicating particular messages about masculinity and social standing in the Victorian era? His dark jacket and the crisp white shirt suggest affluence, and perhaps profession. Curator: Precisely, those visual symbols of professional standing create powerful and enduring associations with the person represented. The meticulous grooming—the neat beard, for instance—speaks volumes about societal expectations, a silent language accessible across time. Editor: The gaze is also important. He makes direct eye contact, seemingly confident yet maintaining an appropriate level of decorum, given the period's constraints. There's a sense of cultivated seriousness that aligns with the broader narratives of Victorian masculinity—duty, respectability, self-control. But there’s a counter-narrative suggested by his somewhat unconventional pose with hand-to-face; is he contemplative or just tired? Curator: That small hand-to-face is also revealing, potentially offering a vulnerable point of connection to a modern audience accustomed to more overt displays of emotion. I like how it allows us a certain intimacy with this historical person, someone often revered and set apart from us. Editor: For me, contextualizing photography from the 1860s reveals not just an individual but larger questions around empire and labor, and how image culture might serve a function in upholding hierarchical systems. This image freezes time to create an upper-middle class, which can obfuscate some political and economic inequalities in England at that time. Curator: By analyzing these portrait prints as cultural symbols, we gain insights not just into a specific individual's life but into the prevailing attitudes and collective values that shaped a given era. Editor: Definitely, this dialogue reveals some of those nuances that would be missed if you just looked at the image. It also reveals assumptions around race, class, and gender that influence our relationship to photography and art.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.