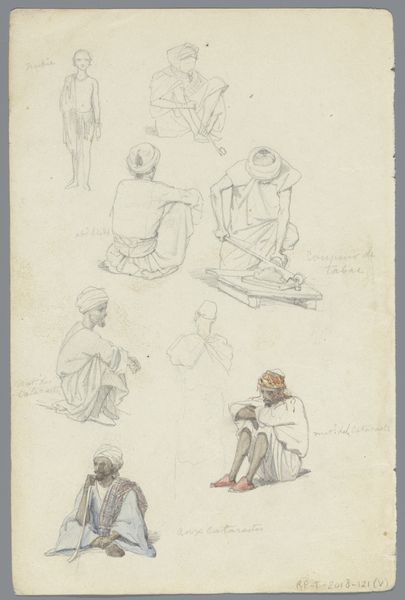

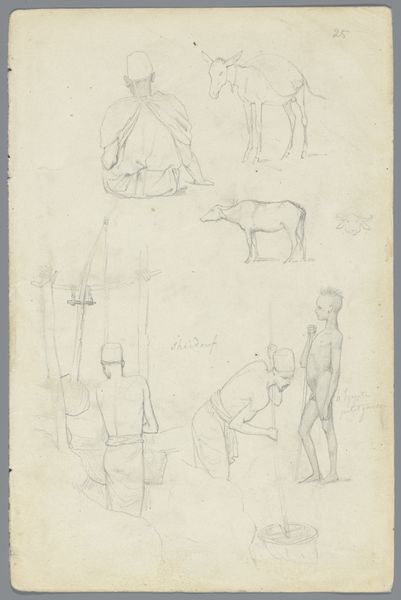

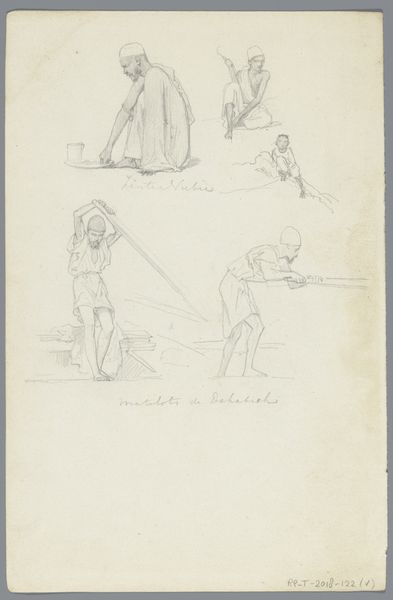

drawing, pencil

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

pencil sketch

#

ancient-egyptian-art

#

pencil

#

academic-art

Dimensions: height 191 mm, width 126 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This is Willem de Famars Testas' "Five Studies of Egyptians and Two Heads Ditto", a pencil drawing dating back to around 1858-1859. It's currently part of our drawings collection. Editor: The first thing that strikes me is the seeming lightness, almost ethereality of it. The pencil work creates a sense of movement and fleeting observation, almost like capturing a series of moments. Curator: Absolutely. Testas was deeply interested in Orientalism, and this drawing provides a fascinating window into how Egyptians were viewed and depicted during that period. He's capturing a visual inventory, almost like a collection of ethnographic specimens, if we’re being critical. The artistic intention reflects both documentation and exotification. Editor: Thinking about the material – just pencil on paper – makes me consider its immediacy and the potential accessibility of the artistic process itself. This wasn't a commission of precious metals or lavish oils; this was a readily available, humble medium. Does that contribute to a sense of the "everyday" in his depictions, despite the Orientalist lens? Curator: I think that’s a valid point. The choice of medium arguably emphasizes a documentary approach but perhaps obscures how class dynamics, power, and colonialism were literally inscribed onto those Egyptian bodies, translated through Testas’ own European positionality and perception. Editor: And what do we know about how these studies were actually made? Was it on-site sketching, or were these compiled later, perhaps in a studio from other visual sources? It shapes how we read the work, as on-site would embed an encounter while working from secondary images highlights the distance in perception and interpretation. Curator: Archival information shows that he traveled extensively through the region. We believe it’s safe to assume he created these studies whilst encountering these people, in Egypt. But the question of how direct those interactions were, how reciprocal, still stands. His visual language reinforces existing stereotypes, ultimately reflecting the exoticising male gaze that permeated artistic expression during his period. Editor: Seeing these quick strokes, this method of almost immediate reproduction, does make me think of labour, the swift translation of observed human forms, almost production line style to churn out this image which eventually others then consume… Thank you, that perspective has changed my understanding of this study. Curator: Glad to offer my reading, just like a reminder to myself to constantly challenge dominant cultural paradigms and ask who has the power of representation in the history of art.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.