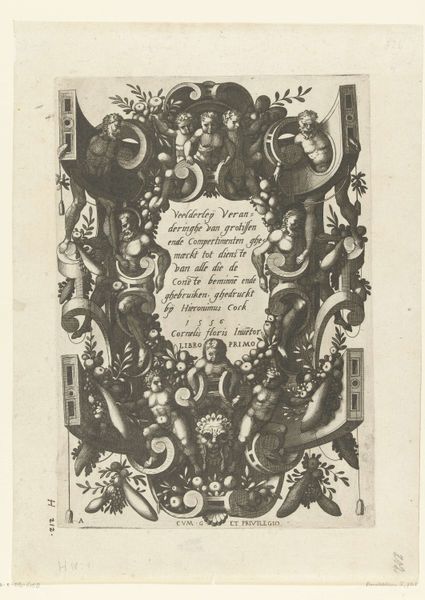

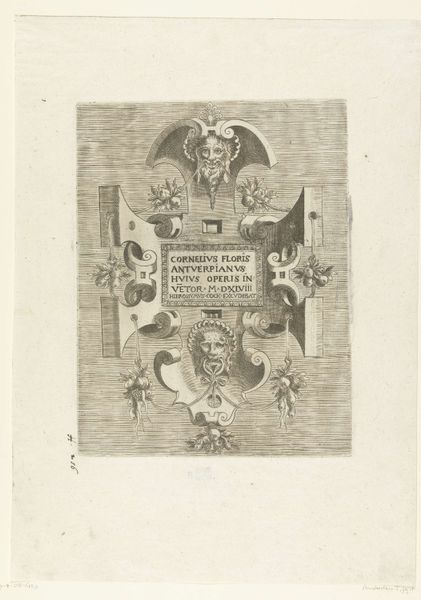

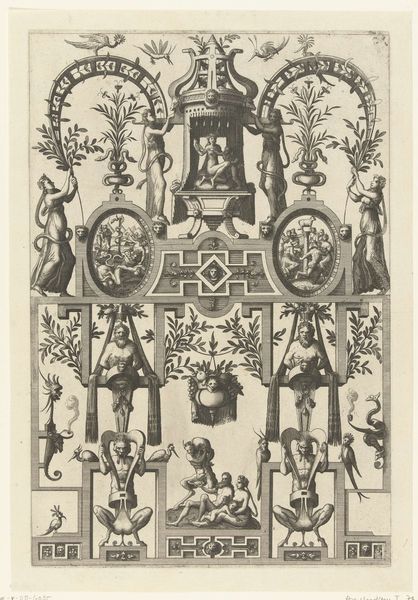

Vlakdecoratie: cartouche in omlijsting van rolwerk met figuren 1557

0:00

0:00

johannesoflucasvandoetechum

Rijksmuseum

drawing, print, engraving

#

drawing

#

allegory

# print

#

mannerism

#

figuration

#

11_renaissance

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 308 mm, width 207 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

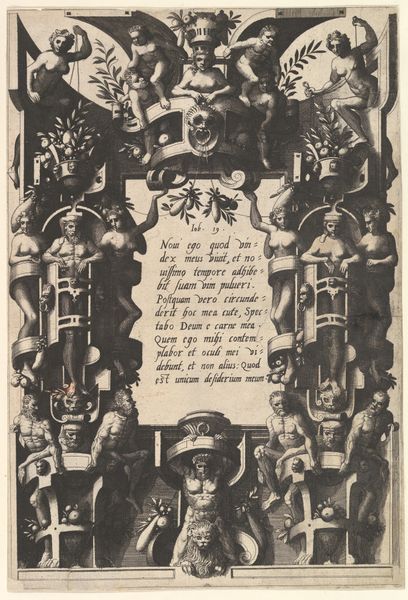

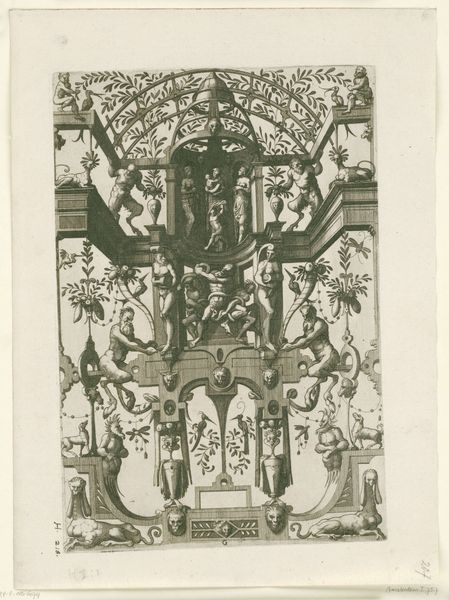

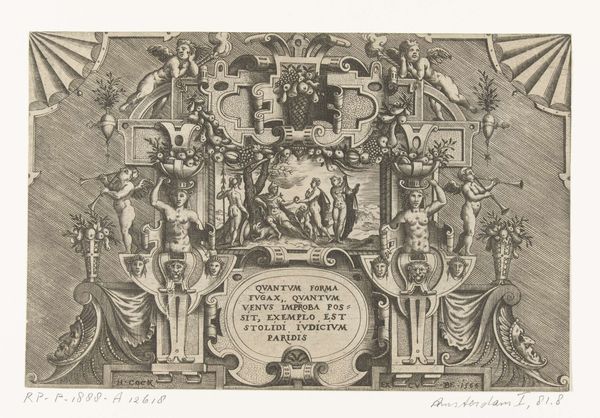

Curator: This engraving, "Vlakdecoratie: cartouche in omlijsting van rolwerk met figuren", dates to 1557, crafted by Johannes or Lucas van Doetechum, and it resides here at the Rijksmuseum. It presents a richly ornamented cartouche typical of Mannerist design. What’s your first take on it? Editor: My initial impression is of visual overload! So many figures crammed into such a small space. It gives the piece a tense, almost claustrophobic energy. The stark contrast emphasizes that intensity too, no gentle shading here. Curator: Indeed. Notice how the profusion of allegorical figures—cherubs, classically inspired nudes—aren’t merely decorative. The composition itself functions as a symbolic language. It draws deeply from Classical antiquity, revived and reinterpreted through the Renaissance lens. Editor: And speaking of lenses, I can't help but see this through the prism of its historical moment. This densely ornamented style served as a marker of status and education in a society rigidly structured by power dynamics. Its visual complexity and classical references would have signaled the patron’s sophistication. Curator: Absolutely. Furthermore, there’s the symbolic use of architectural elements—the cartouche itself, the scrolling ornamentation—that function as frameworks to elevate the written word. Words, after all, were viewed with immense cultural authority in that era. Editor: Yet that text itself—seemingly Latin, given the 'Deum' reference—isn’t particularly revolutionary, right? Perhaps from the Book of Job? To my eyes, the surrounding ornamentation almost drowns out any meaning the written portion would convey. It suggests less an engagement with divine concepts and more with asserting earthly dominion through artistry. Curator: That's a valid perspective. But let’s not dismiss the emotive pull inherent in religious imagery. Beyond sheer display, Renaissance prints offered an accessible portal into deeper faith reflections, especially amidst theological reformation. Editor: I concede to that. The power of reproducible images allowed broader access. Still, I keep coming back to the feeling of excess—anxiety expressed via artistic language about asserting one's self during shifting times. Curator: Perhaps you're right. The weight of interpretation continues to shift with each viewing and each era that reflects upon it. Editor: It's a valuable point: we can learn a lot by acknowledging how the times inevitably color what and how we see.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.