drawing, pencil

#

portrait

#

pencil drawn

#

drawing

#

aged paper

#

light pencil work

#

baroque

#

pencil sketch

#

sketch book

#

classical-realism

#

figuration

#

personal sketchbook

#

pen-ink sketch

#

pencil

#

sketchbook drawing

#

storyboard and sketchbook work

#

sketchbook art

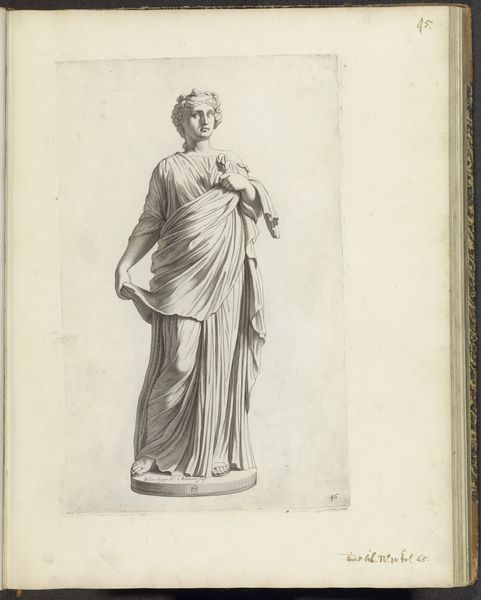

Dimensions: height 366 mm, width 232 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

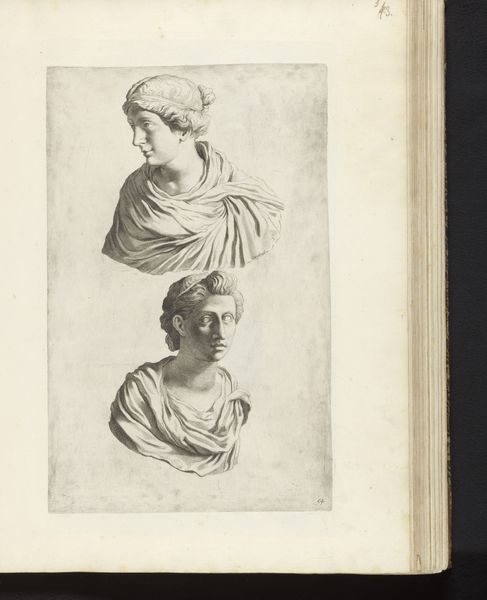

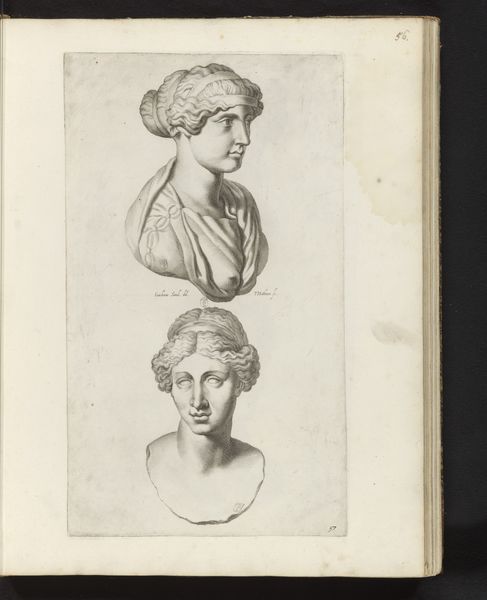

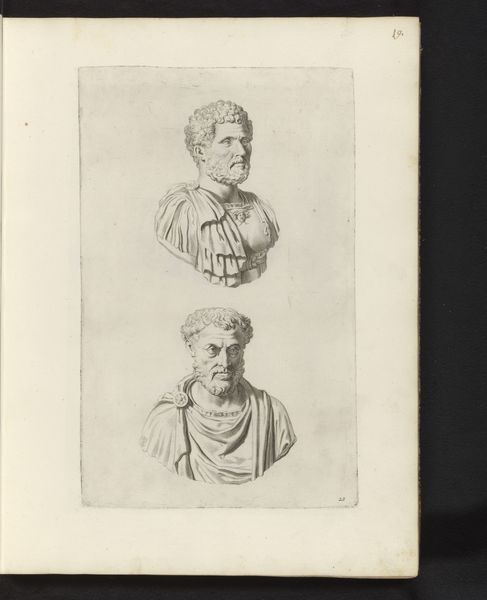

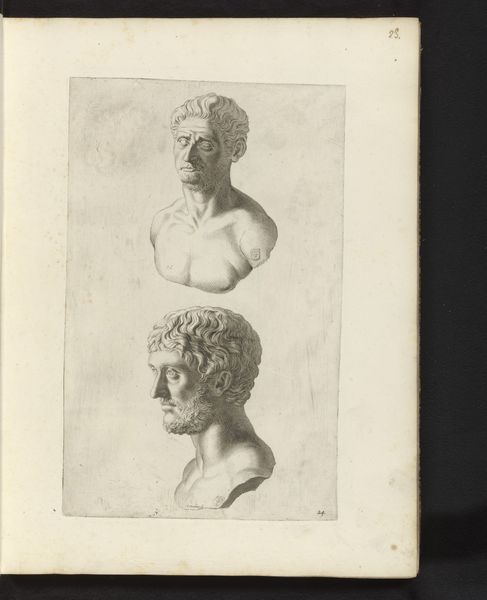

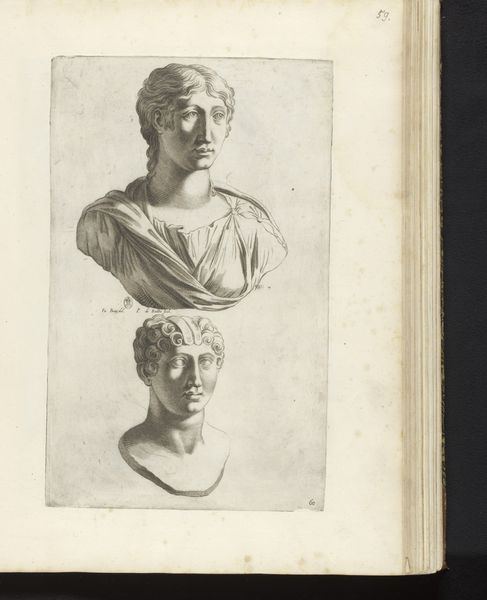

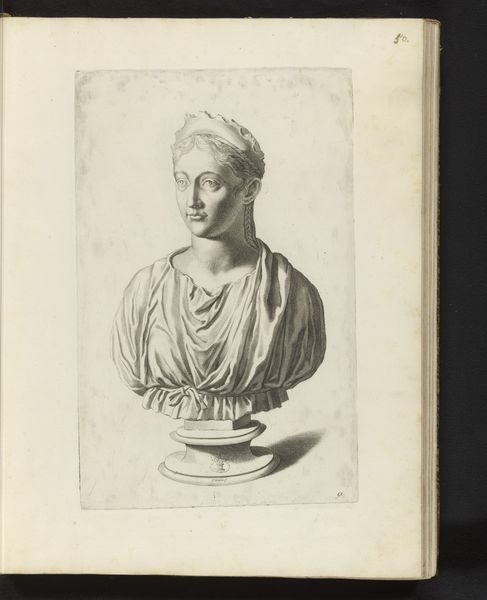

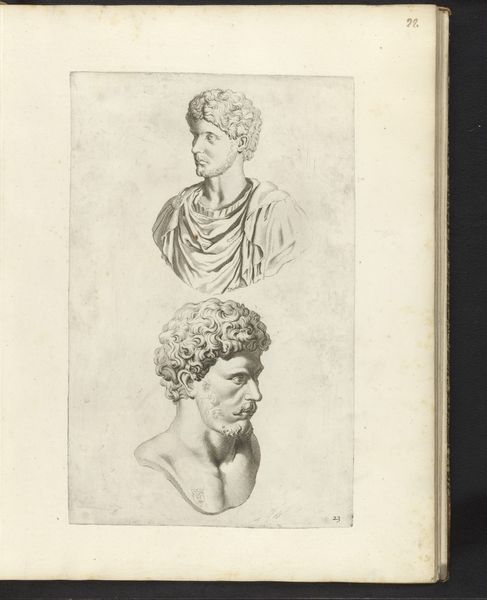

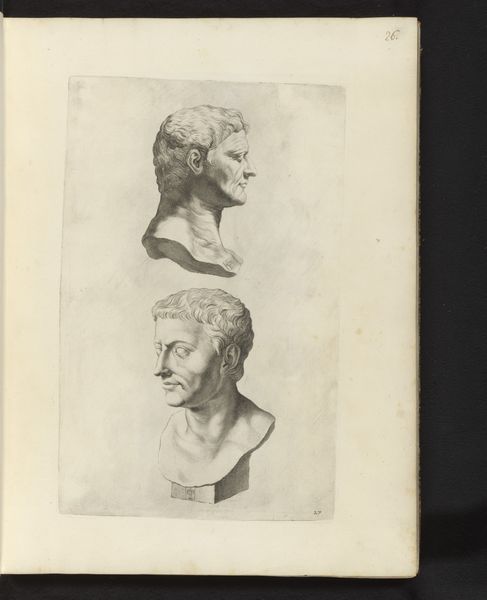

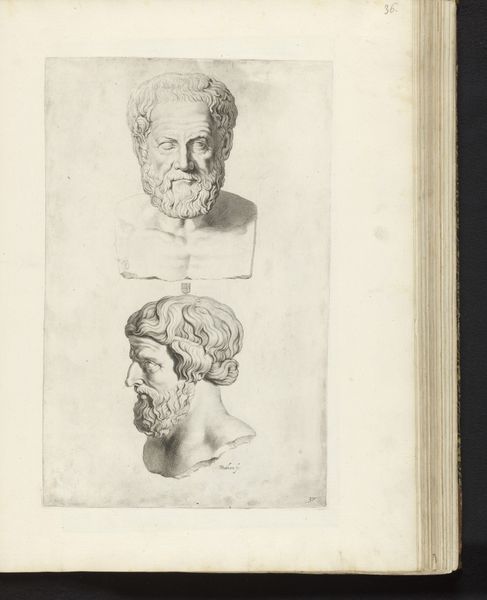

Curator: We're looking at Theodor Matham’s “Bustes van Agrippina en Livia,” created between 1636 and 1647. It's a drawing, part of the Rijksmuseum's collection. Two bust portraits, one atop the other, sketched in delicate pencil strokes on aged paper. My first thought? Quiet dignity. Editor: Yes, immediately there is a serenity, a kind of classical echo in the lightness of the sketch work. It seems provisional, almost. What kind of pencil are we talking about here? Is there evidence of, say, lead mining that speaks to the social context of its creation? Curator: Materially, it’s fascinating as a "drawing" implying, at first, something almost effortless, quickly jotted. But the precise shading and careful construction hint at a slower, more considered process. Perhaps those Roman matrons Agrippina and Livia demanded careful consideration even when quickly rendered. I can see him, the artist, circling them as a sculptor might. Editor: Right! The texture of the paper itself becomes part of the narrative—a foundation literally and figuratively for Matham’s reflections. And thinking about Agrippina and Livia – their lives, their roles in empire building – did the artist access sculptural busts and was reproducing these portraits of power for popular consumption and dissemination? Curator: Good question. Given the period, these drawings likely served as studies or preliminary works for engravings, a more mass-produced medium. I imagine him surrounded by reference books, other prints, using the busts as a model… a very methodical operation despite their "sketchiness." Maybe the slight variation is a touch of flair? Editor: So, process dictates form but the distribution method might reveal some tensions. Consider, too, the original cost versus potential profits. Were these images broadly affordable and could they circulate beyond elite circles. I’d like to dive deep to reveal who these were made *for.* Curator: You make me consider if these pieces, rendered using fairly accessible materials, acted as bridges to these classical ideas, particularly in the rise of the Dutch Republic with newfound wealth. They gave more people the ability to access portraits of such figures who ruled the Roman Empire. In an indirect and subversive way this act helped diminish their mythical stature by bringing their portraits to a mass audience in humble sketches. Editor: An important consideration indeed. Matham’s sketches provide a tantalizing starting point. Looking into the making, and materials transforms the whole interpretation, doesn’t it? It underscores what's there but, as much, highlights the absent history that still echoes quietly within the materials themselves. Curator: Absolutely! Seeing them as something almost more personal, this behind the scenes of the artistic labor that can speak in multiple dimensions on historical context and legacy that would have otherwise stayed on the canvas alone.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.