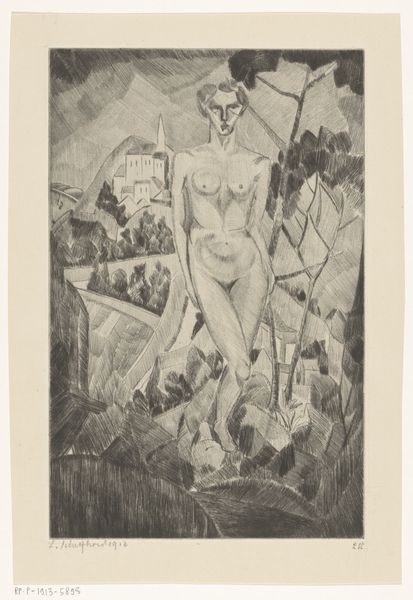

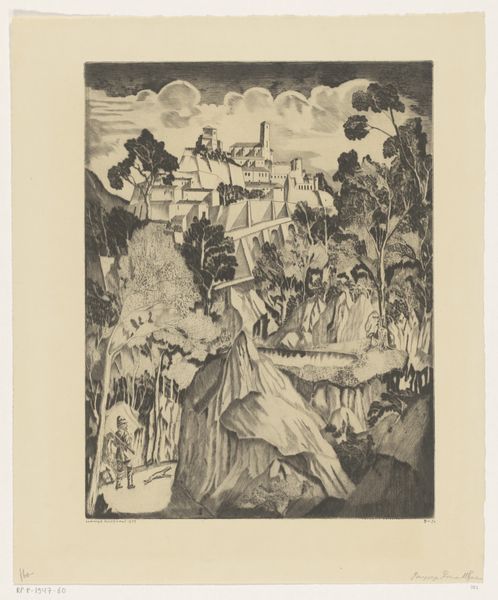

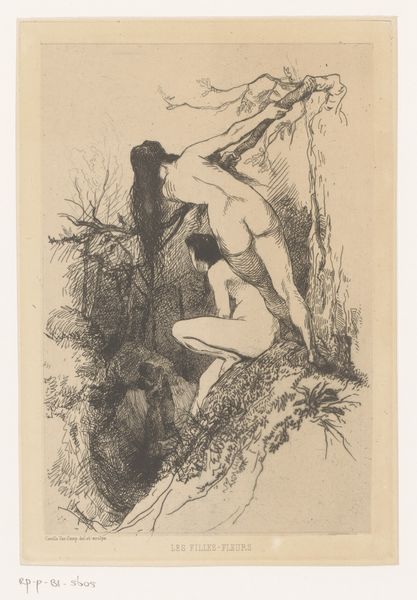

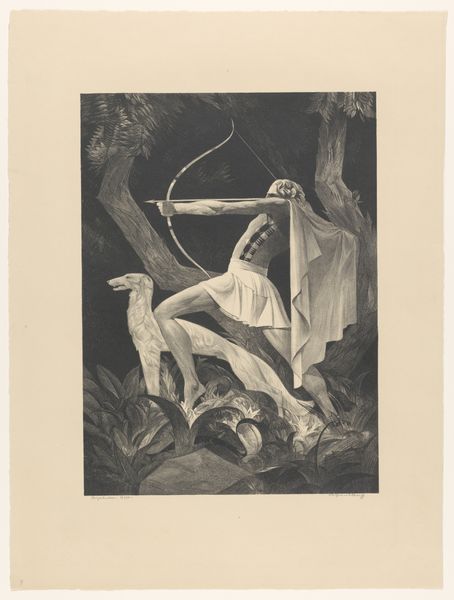

drawing, etching

#

drawing

#

cubism

#

etching

#

landscape

#

nude

Dimensions: height 281 mm, width 182 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This is Lodewijk Schelfhout’s etching, "Naakte vrouw in heuvellandschap," created in 1912. The work, whose title translates to "Naked Woman in Hilly Landscape", is currently held here at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: Well, the first thing that strikes me is how angular everything is. It's a somewhat harsh landscape, reflecting, perhaps, a break from the idealised feminine form. Curator: The influence of Cubism is undeniable, particularly its fragmentation of form and perspective, however Schelfhout maintains clear thematic connections to landscape. It reveals how modern movements played out even in the visual depictions of the human form, especially given how this piece emerged within a time of social upheaval. The nude in art historically has been a form that has reflected power structures, ideas of beauty and identity; Schelfhout subverts some of the established notions through the fragmented style. Editor: The symbols seem to blend, almost fight for prominence, don't they? The rural idyll—that small town, church spire—competes with a very modern and deconstructed figure, which traditionally has had the connotation of natural. Curator: Precisely! Consider also the accessibility of etchings as opposed to other forms such as oil painting or monumental sculpture; there’s an inherently democratic aspect in how widely it can be circulated. The very decision to disseminate this piece in such a format places the symbolism, which you highlighted, in direct contact with a wider populace and generates questions around access and interpretation of art during this period. Editor: What really grabs me is that the central figure seems so vulnerable, almost exposed. But because of how it is done, how fragmented the form is, it is simultaneously protected and impenetrable. In the classical use of nudes, the woman figure typically expresses submission, inviting admiration or lust. Curator: But here we get that tension with cubist and modern conventions…a far cry from Ingres's or Bouguereau's works, whose figures held allegorical ties to classical themes like Venus and Aphrodite. We are seeing the figure redefined not within the conventional, dominant structures. It makes me curious how this image was initially perceived by viewers accustomed to more classical representations of women. Editor: Right. Instead, it’s fragmented, challenging our reading. There’s something quite defiant about it. Curator: A defiance perhaps born from both the revolutionary art movements as well as shifting roles of women in the early 20th century. Food for thought.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.