photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

portrait

#

photo restoration

#

pictorialism

#

photography

#

portrait reference

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

19th century

Dimensions: height 164 mm, width 108 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

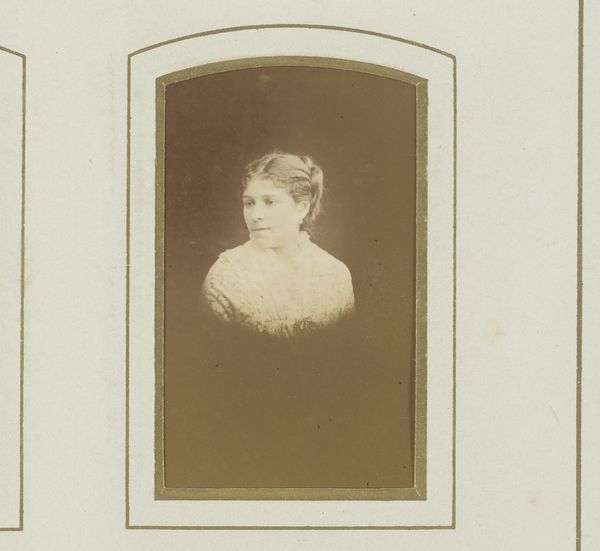

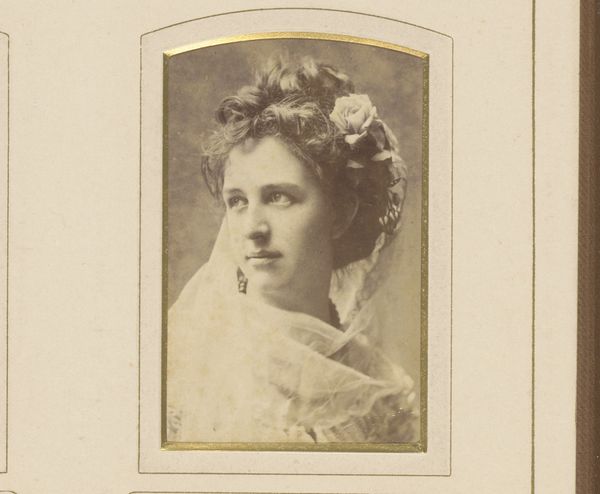

Curator: This gelatin-silver print, "Portret van een vrouw, aangeduid als Mme. Martin," dates to sometime between 1870 and 1900. It captures the sitter in profile. Editor: There's a melancholic air to it, a kind of fading beauty. The oval frame gives it such a sense of containment. Almost like a pressed flower in an album. Curator: It's intriguing how portraiture shifted with the rise of photography. Before, painted portraits were the domain of the wealthy, but now photography offered a wider audience access to memorializing themselves. What kind of statement do you think a portrait like this made in its time? Editor: It signaled belonging, didn't it? To have your likeness rendered, even photographically, suggested a degree of social standing, permanence, and family connection. But consider her gaze; it isn't assertive or challenging, more like quietly observing, passively receiving attention. The locket she's wearing is a lovely personal detail. Curator: Lockests were popular for holding portraits, so her necklace is effectively containing another layer of representation, maybe family, maybe a loved one passed. Note, also, the limited tonal range in the print; that adds to the romantic and slightly sentimental atmosphere. It would resonate with then-current ideals about feminine beauty and sentimentality. Editor: Sentimental, yes, and maybe that was intentional. The pictorialist aesthetic aimed to elevate photography to the level of art by imbuing it with painterly qualities. That softness almost masks the realism photography is known for. Curator: And the softness lends it this otherworldly feel, right? Which only serves to emphasize her idealized beauty. But it also raises a point on authenticity. It's photography, yes, but how much of "Mme. Martin" are we actually seeing here? Or are we presented with a fiction carefully constructed and preserved. Editor: Ultimately, it speaks volumes about how individuals wished to be seen and remembered. It also shows us how much we need images to locate people across the time, whether as a keepsake of identity, a political prop, or just something nostalgic that triggers an unnamable sense of memory. Curator: Very well observed. It reminds us that cultural memory resides in these traces that continue to evoke ideas about presence and absence in ways we hadn’t perhaps considered before.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.