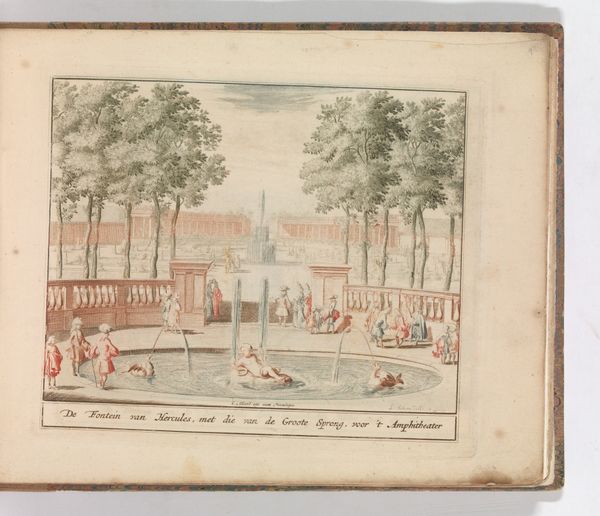

" ’t Konings Huis op 't Loo", in: Tooneel Der Voornaamste Nederlands Huizen, En Lust Hoven, Naar T Leven Afgebeeld 1660 - 1693

0:00

0:00

drawing, print, etching, paper, engraving

#

drawing

#

baroque

#

ink paper printed

# print

#

etching

#

book

#

landscape

#

paper

#

cityscape

#

genre-painting

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: Plate: 6 9/16 × 7 3/4 in. (16.6 × 19.7 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Before us is “’t Konings Huis op ‘t Loo” from Carel Allard’s "Tooneel Der Voornaamste Nederlands Huizen, En Lust Hoven, Naar T Leven Afgebeeld,” dating from sometime between 1660 and 1693. Allard was a master of printmaking; this piece utilizes etching and engraving, ink on paper. It's part of a larger book, actually. Editor: My immediate thought is of the elaborate formality. It's so rigidly composed, like a stage set. The scale seems miniature, almost like a dollhouse rendition. There's such meticulousness in the linework and detailing of the figures. Curator: Well, think about the social context. This was the Dutch Golden Age. Allard was creating imagery for a wealthy merchant class eager to display its status. The precision reflects an investment in portraying a specific kind of order, a new national identity. It suggests Dutch cultural power but it also echoes themes of colonization at the time. Editor: Exactly. Consider what that constructed perspective actually means. That manicured avenue doesn't exist in a vacuum; it likely represents a society built on exploited labor and resources both domestically and abroad. It prompts important questions about the socio-political dynamics of the era. The figures are very doll-like, rendered almost anonymous, a means of displaying the power of architecture itself. Curator: I see your point. The image is presented through a printed book and meant to be replicated for mass audiences in this wealthy society. So we have a carefully fabricated scene depicting the ruling elite through widely disseminated prints. This speaks volumes about both aspiration and the construction of power in that era through mass culture. Editor: I agree. The use of linear perspective reinforces the control exerted by the Dutch elite, visually projecting dominance over space. This controlled avenue also invites reflection on class and social hierarchies during the Dutch Golden Age. We have to consider art within larger socio-historical narratives; only then can we truly understand its impact. Curator: Looking at this image, I'm now compelled to consider what it tells us about seventeenth-century attitudes towards property and the display of wealth in relation to colonial exploits. Editor: Absolutely. We must continuously re-examine history, even in seemingly serene landscape prints. By interrogating these idyllic scenes, we uncover a wealth of meaning.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.