Albumblad met drie prenten met twee geliefden, een schaal en het martelen van Felicitas van Rome 16th century

0:00

0:00

balthazarvandenbos

Rijksmuseum

drawing, ink, pen

#

drawing

#

allegory

#

pen sketch

#

figuration

#

11_renaissance

#

ink

#

pen-ink sketch

#

pen

#

history-painting

#

miniature

Dimensions: height 430 mm, width 292 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

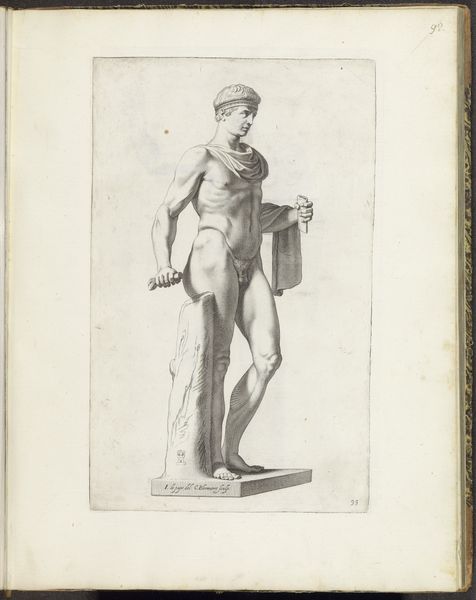

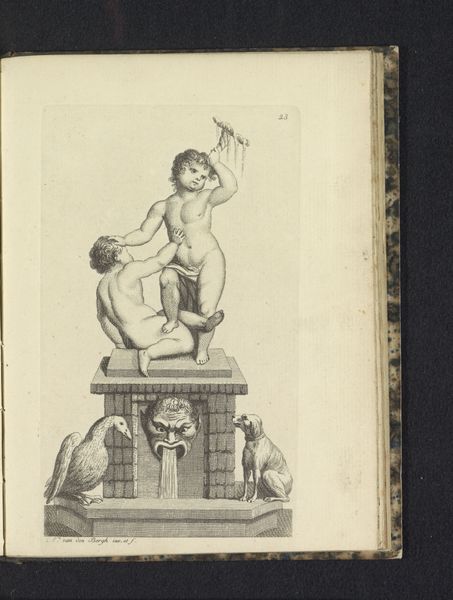

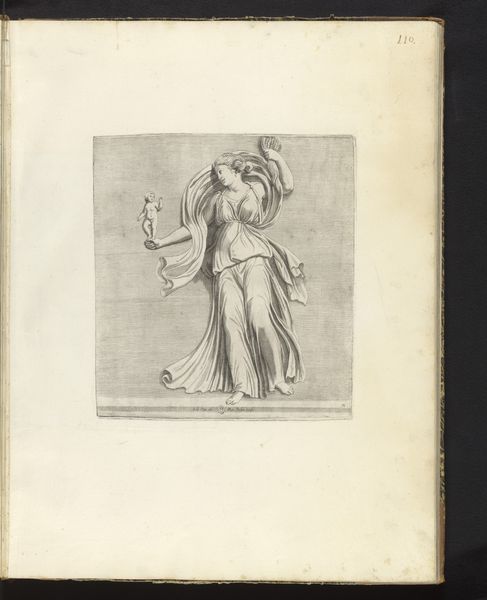

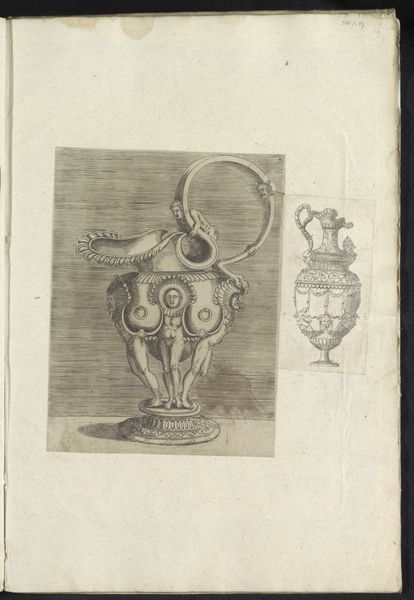

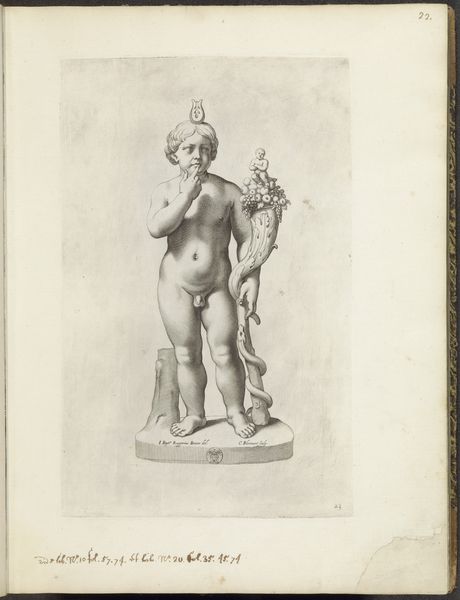

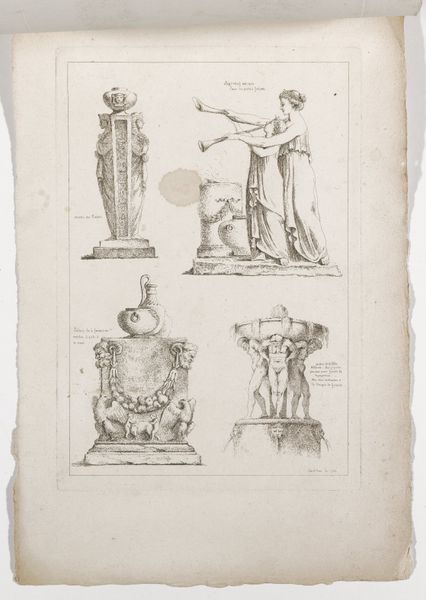

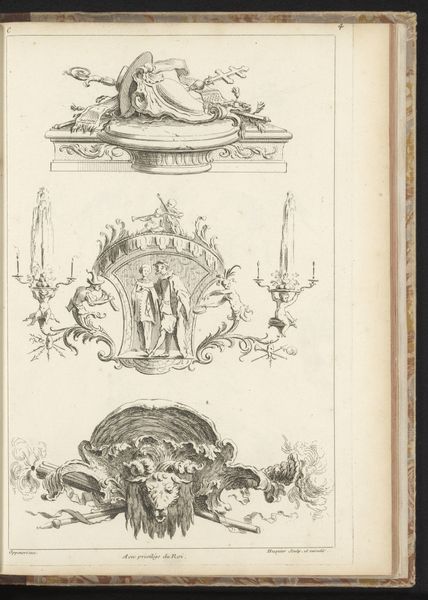

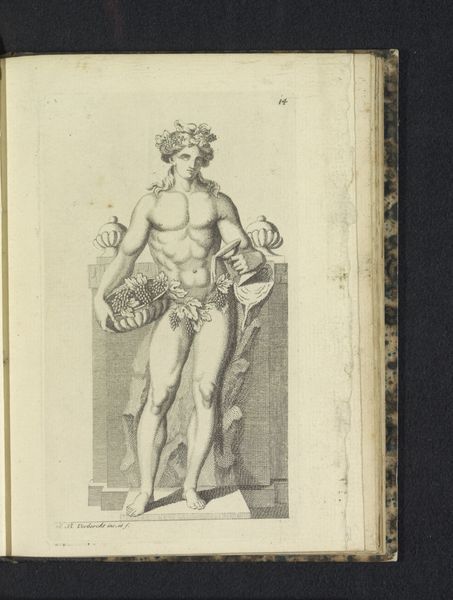

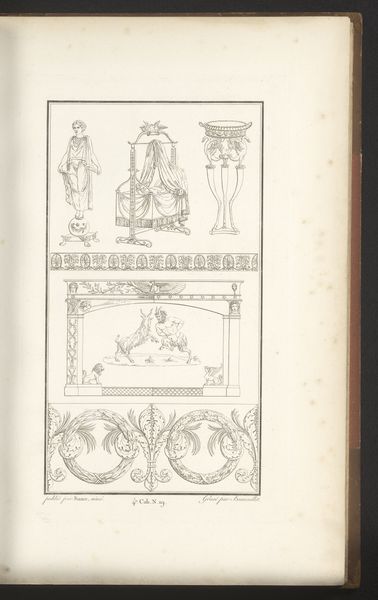

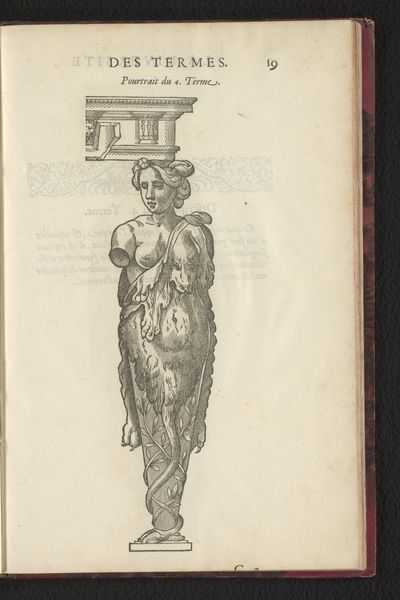

Curator: Here we have an intriguing page, "Albumblad met drie prenten met twee geliefden, een schaal en het martelen van Felicitas van Rome," a 16th-century Dutch pen and ink drawing from the Rijksmuseum. Editor: It's certainly... busy. My immediate impression is one of disparate narratives competing for space. There's tenderness in the embracing couple, violence in the scene above, and a kind of opulent classicism in that vessel. How do they relate, do you think? Curator: From a material perspective, these seem to be collected impressions, likely engravings pasted onto a single sheet. The paper stock seems typical of the period, perhaps even mass-produced given the relative affordability of prints by that time. This challenges the modern notion of a single, cohesive artwork, instead reflecting an album meant for browsing, collecting, and perhaps even inspiring other artists. Editor: That's interesting. So, not so much a unified statement as a collector's scrapbook, almost? The images themselves, especially the martyrdom of Felicitas, place it within a visual language very familiar in the context of religious and political conflict. And the lovers, alongside this grand chalice... Is it trying to speak to concepts of virtue and vice, perhaps, juxtaposing the ideal with lived experience and violence? Curator: The placement could certainly imply a relationship the compiler wished to create. And consider the labor involved in producing these prints. These images were intended for dissemination, allowing widespread access to both biblical narratives and classical motifs that would have previously only been accessible to elites. Editor: Which is precisely how they become politicized, right? The imagery of martyrdom, circulated broadly, serves to solidify group identity, fueling resistance or religious fervour. The album itself becomes a tool, albeit a small one, in a larger ideological struggle. Curator: Indeed, even the inclusion of that finely wrought chalice suggests an interest in power, whether religious or secular. Editor: Thinking about it, the album provides a context itself. Collecting, arranging, showing and interpreting are political acts, and it all makes me look at it from the point of view of its audience. Thank you, it’s an image that tells so much of its time, but thanks to you, also says so much more than meets the eye. Curator: Absolutely. Analyzing this “albumblad” offers fascinating insights into the modes of artistic production and visual consumption in the 16th century, moving beyond aesthetics to highlight the vital roles of materials and production within that world.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.