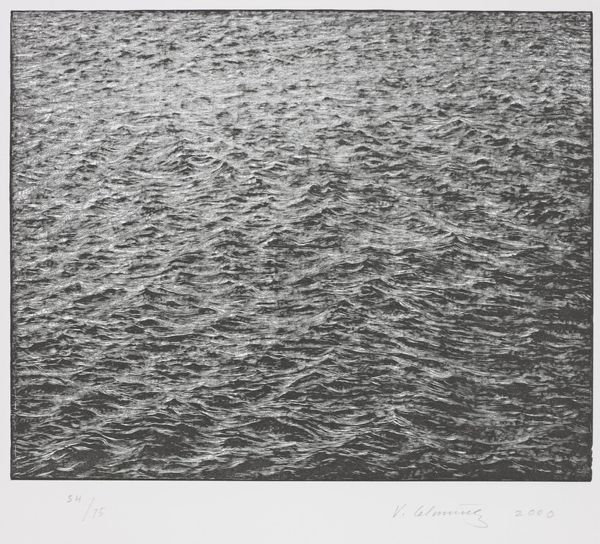

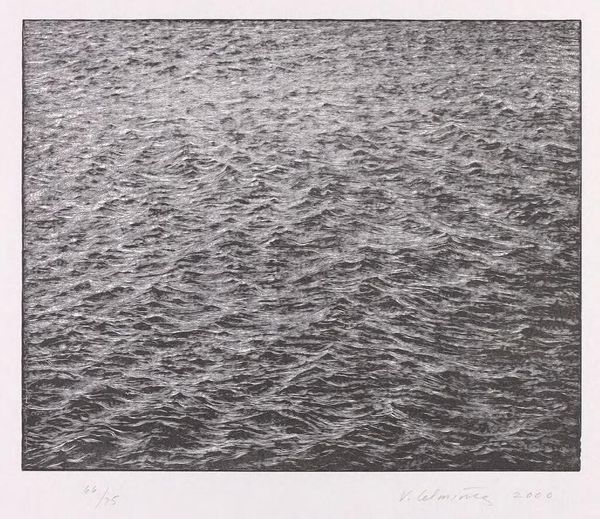

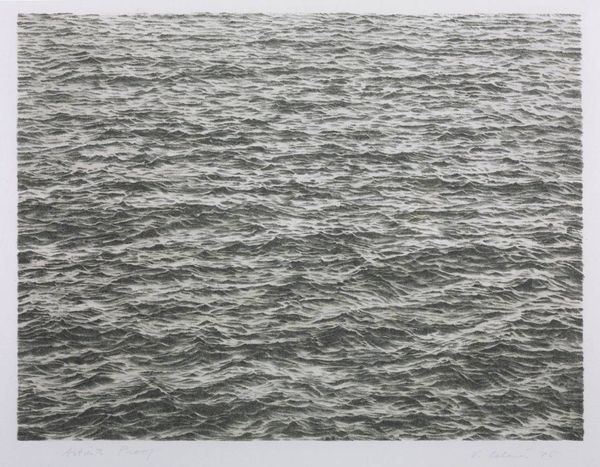

print, photography, drypoint

# print

#

landscape

#

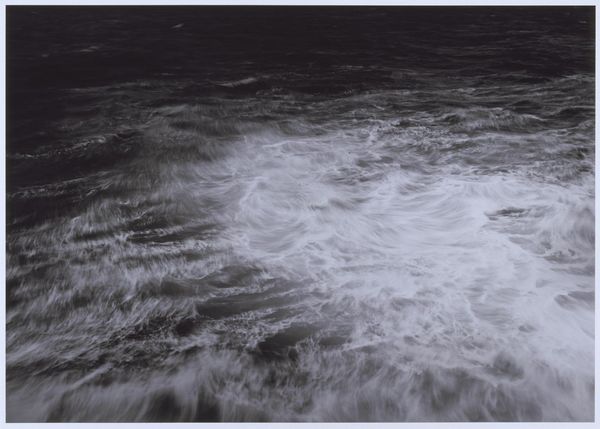

photography

#

ocean

#

water

#

drypoint

#

realism

#

sea

Copyright: Vija Celmins,Fair Use

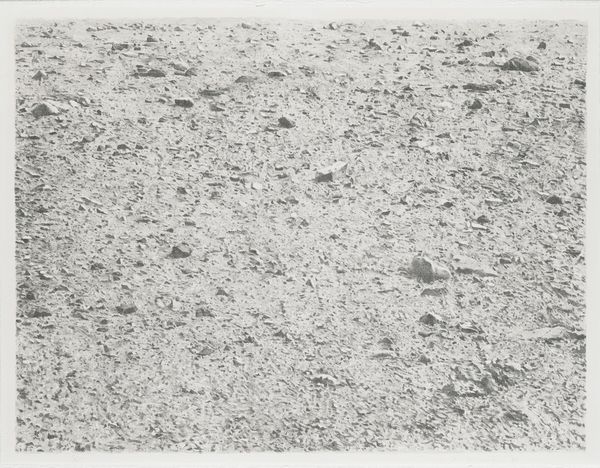

Curator: The artwork before us is titled “Drypoint - Ocean Surface.” Created by Vija Celmins in 1983, this piece, housed here at the Tate Britain, utilizes the drypoint printmaking technique to capture a vast expanse of the ocean. Editor: Immediately, I'm struck by the quiet intensity of this piece. It's so meticulously rendered, almost photographic in its detail, yet the monochromatic palette lends it a certain detachment. It feels vast, yet intimate, calming, but also slightly unsettling. Curator: Celmins, throughout her career, has been interested in representing seemingly neutral subjects – oceans, deserts, the night sky. But this is far from politically neutral in our current landscape. We must recognize these images now, in an era of ecological crisis, carry the weight of a changing planet. Consider the violence inflicted on these landscapes and peoples by colonial exploitation. Editor: Absolutely, the selection of the subject can be interpreted through today's ecological concerns, however, historically, this ties into the tradition of landscape art which often carries its own political weight, reflecting ideas of territory, ownership, and even national identity. Drypoint, with its sharp lines and potential for delicate gradations, offers Celmins the opportunity to highlight this tension. It imitates a photo, a documentary act, and thus feels extremely contemporary. Curator: Exactly, but thinking intersectionally, this is not simply a picture of water. This is the nexus of rising tides, refugee crises, historical injustices enacted by naval dominance across colonized lands. By removing the horizon line, Celmins removes a point of reference and orients the viewer in a position of disequilibrium. Editor: That is so true, removing the horizon emphasizes the endlessness, and perhaps the unknowability of the ocean. It invites a meditation on the surface itself – the play of light, the texture of the water and this play, this rendering asks us to see value in something many dismiss as background. How has this representation of landscape become aestheticized while we actively damage that very thing? Curator: Precisely, how does the gallery as a physical space influence our reception? Knowing it is hanging on the walls of the Tate brings ideas about empire and maritime dominance to mind. Looking closely now, notice how, upon even closer examination, it almost abstracts into a field of marks, revealing the process of its creation, of printmaking, a sort of controlled chaos that mimics the ocean's unpredictable nature. Editor: I agree, recognizing those delicate intentional marks that capture an essence. To consider the process is, ultimately, an optimistic exercise, allowing us the realization that while daunting and ever-changing, we are actively able to alter our relationship with such natural phenomenon.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.