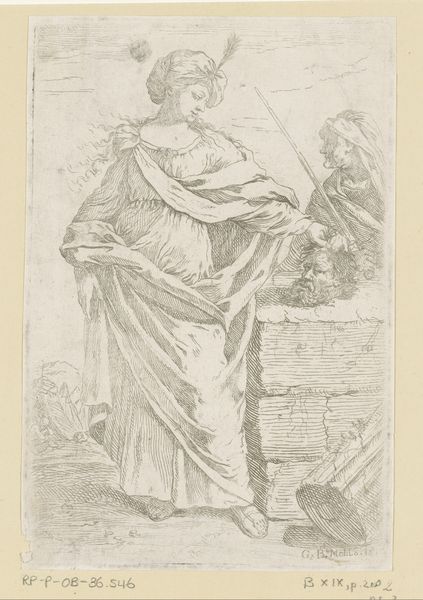

Dimensions: height 297 mm, width 202 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: So, here we have "Muze met uitgestrekte arm," made sometime between 1746 and 1793 by Louis Marin Bonnet. It's a print, combining etching and engraving techniques, depicting a standing figure. There's almost a softness to it despite being a print, a certain... lightness of touch. What jumps out at you? Curator: The question isn't just what is *depicted* but how was it made, right? Look at the labour involved: the careful hatching, the precision needed for the engraving tools on the copperplate. This wasn't just a quick sketch. Consider, too, that Bonnet was replicating, making multiples. Was this for widespread consumption? A democratizing gesture, making classical ideals accessible? Editor: That's a good point – how accessible *were* prints like these at the time? Did it challenge traditional notions of unique, "high" art objects? Curator: Precisely! Etching and engraving were, in a way, early forms of mechanical reproduction. Were these prints regarded with the same reverence as paintings? Did the process—the deliberate, repetitive act of creating the plate, the printing, the dissemination—affect how people valued the image itself? Were these luxury items, or aimed at a middle class? Editor: I see. Thinking about the materials and the making of the art really opens up new ways to interpret the final image, to ask, *who* was it really for and what message did they take from it, understanding how prints are consumed and how that affects art's broader role in culture! Curator: And remember, the economic structure drove that ability to see. Now, thinking about today, how many people only ever see reproductions and not original work?

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.