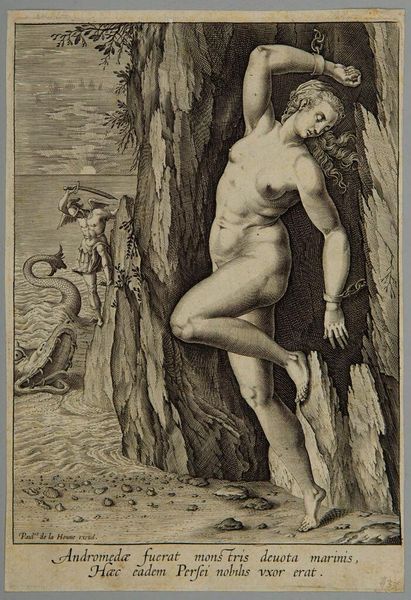

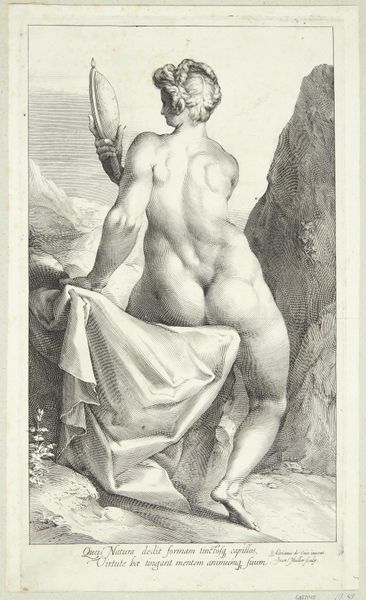

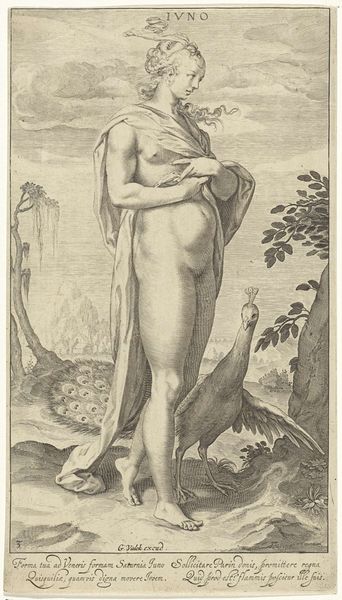

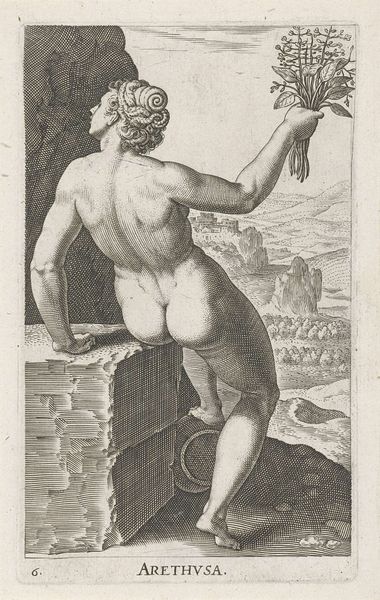

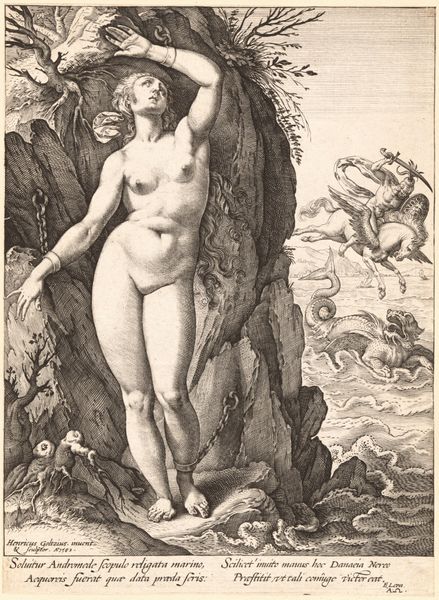

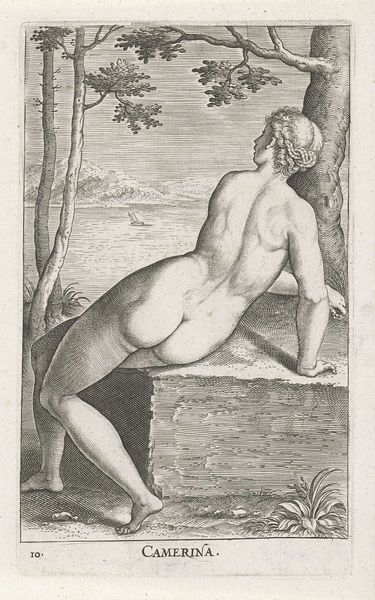

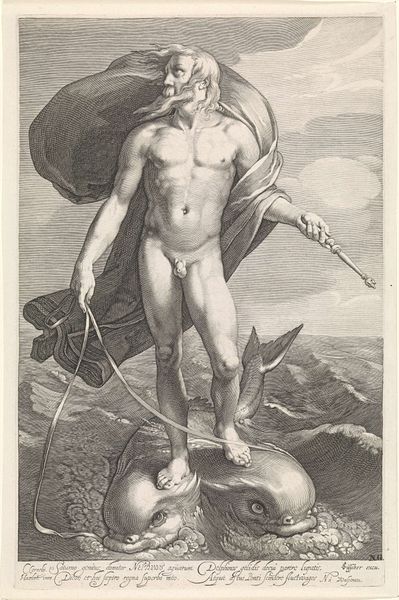

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

pencil drawn

#

baroque

# print

#

old engraving style

#

portrait drawing

#

history-painting

#

nude

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 214 mm, width 145 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Wenceslaus Hollar's "Johannes de Doper in de woestijn," created in 1642, presents an interesting tension through the very medium of printmaking. It's not just the image itself, but how the means of production inform its meaning. Editor: I see, an engraving showing John the Baptist nude in the wilderness. It has an almost unsettling rawness to it. The figure is so exposed, amidst a stark landscape rendered in incredibly fine lines. What stands out to you most about this work? Curator: Think about the labour involved. The fine lines you mentioned—those are the product of hours, perhaps days, of painstaking work with a burin. The plate, likely copper, would have been incredibly valuable. Yet, this expensive material and intense labor are used to depict a figure of asceticism, a man rejecting material comfort in the desert. How do we reconcile that contradiction? Editor: So the choice of materials highlights a sort of... irony? This elaborate, almost decadent, process depicts a rejection of earthly pleasures? Curator: Precisely! The print also raises questions about dissemination and consumption. Engravings were reproducible, making art accessible to a wider audience. Does the mass production cheapen the religious experience or amplify its message by bringing it to more people, considering the class dynamics of seventeenth century society? Editor: That's fascinating. It makes me think about the economics of religious art at the time. Curator: Exactly. This piece makes us consider not just the visual representation, but the complex network of production, distribution, and consumption that shaped its meaning for its original audience. It invites questions about labour, access, and the material conditions of religious experience. What have you gathered? Editor: I now see how focusing on the material production, the choice of printmaking itself, reveals a whole new dimension to interpreting this artwork beyond the surface-level representation.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.