Dimensions: height 203 mm, width 151 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

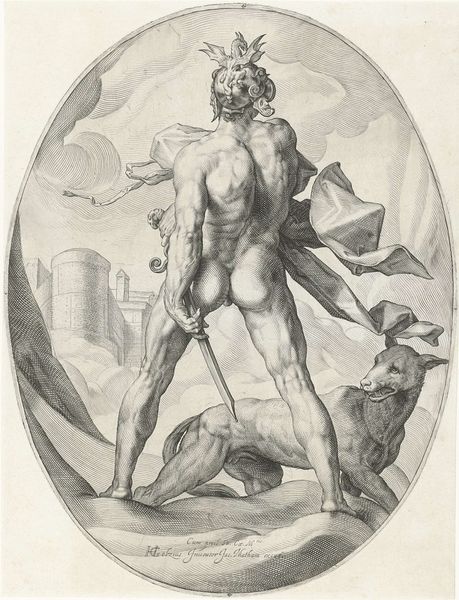

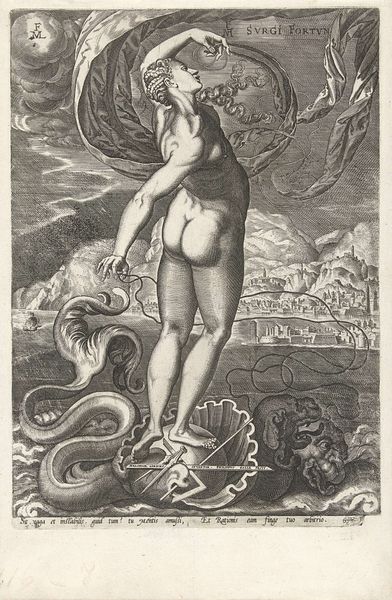

Curator: Welcome to the Rijksmuseum. We're standing before Jacob Matham's engraving, "Juno," created between 1585 and 1589. Editor: My eye is immediately drawn to the swirling cloudscape. It’s quite dynamic. The line work, especially in the drapery and the feathers of the peacock, creates a wonderful texture. Curator: It's a classic allegorical representation of Juno, queen of the gods. What interests me is how Matham negotiates the artistic conventions of the period with the demands of his patrons. The inclusion of Juno, the peacock, all these signal power and authority. These images reinforce existing hierarchies. Editor: I see what you mean, but let's look at the positioning of the figure. Her back is turned to the viewer. There’s an intriguing sense of modesty combined with the display of classical form. The engraver really understood contrapposto, using line to define musculature and create an elegant S-curve in her pose. Curator: True, and in its original context, prints like this circulated widely, serving as a key form of visual communication and even, dare I say, propaganda. Images of classical figures were particularly effective in establishing links between a patron’s own power and the legacy of the Roman empire. Editor: I hadn't thought about that but these images probably influenced fashion and taste more broadly at the time, as they were some of the only visual sources. Look at the use of light and shadow. It really guides the eye. See how it moves from her back and shoulder down her arm towards the peacock. It’s masterful, really. Curator: What you’re seeing as artful rendering would have also been very practical. These images allowed the elite to see themselves as the rightful inheritors of a classical legacy, thus contributing to an intricate game of social and political maneuvering. Editor: So it’s art serving power, and simultaneously striving for its own form of ideal beauty through complex forms and detailed observation of classical ideals. Curator: Precisely. Matham was more than a mere copyist; his works reflect the complex social dynamics of his time. Editor: Thank you for drawing our attention to all these important nuances, offering different interpretations.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.