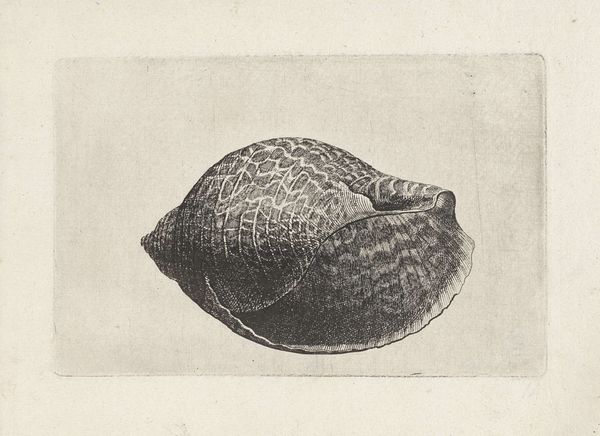

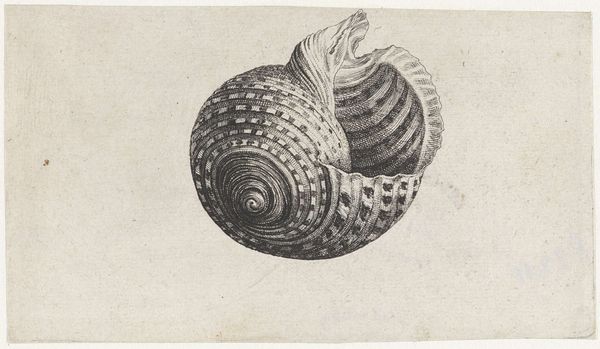

print, paper, engraving

#

baroque

# print

#

old engraving style

#

paper

#

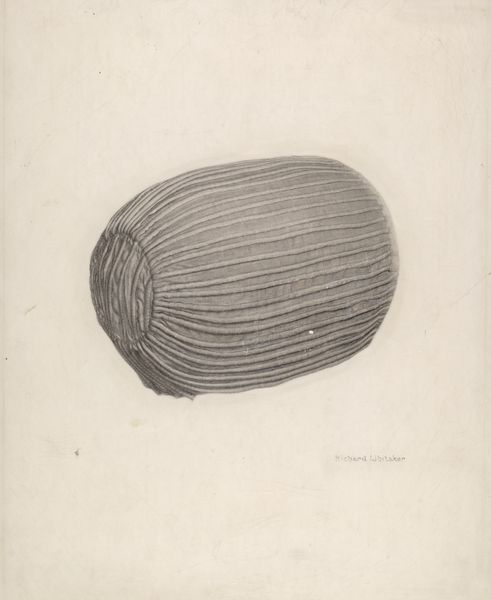

personal sketchbook

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 94 mm, width 140 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

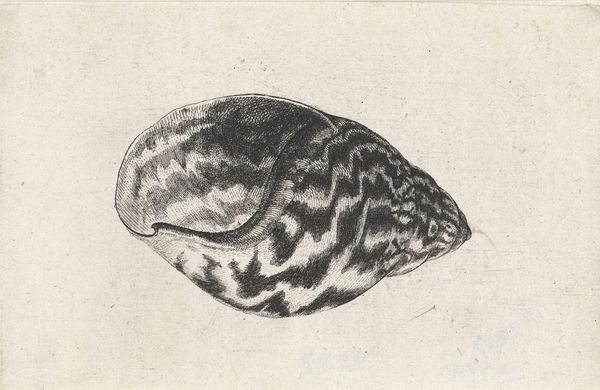

Editor: So this is Wenceslaus Hollar's "Schelp, harpa major," made sometime between 1644 and 1652. It's an engraving on paper, currently at the Rijksmuseum. The detail is really impressive! What stands out to me is the shell’s almost architectural structure, this gridded surface meticulously rendered. What are your initial thoughts? Curator: The detail is striking, definitely. Consider, though, what an engraving like this represents in terms of labor and access. This wasn't just art for art's sake. It was a form of visual information, potentially a scientific record or a decorative motif that could be reproduced and circulated. Who was Hollar producing this for, and what kind of access to shells did they have? Editor: That's interesting, I hadn't thought about it like that. Was Hollar, through his labor, almost democratizing access to images of these natural specimens? Curator: In a sense, yes. Printmaking allowed for a wider distribution than, say, an unique oil painting. And we should also ask what 'value' this work has assigned to the shell as a specimen – a commodity valued for its unique form, available for consumption by European audience. What kind of new meaning does the shell gain? Editor: So, by focusing on the process of creation – the engraving itself – we start to unpack questions of accessibility, knowledge, and the value assigned to objects from the natural world. I guess it highlights how art is always intertwined with its social and economic context. Curator: Exactly. It’s not just a pretty picture of a shell, but an object deeply embedded in its time, in the structures of labor and commodity culture. A tiny print which contains larger implication of class, labor and materiality. Editor: I’ll never look at engravings the same way again!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.