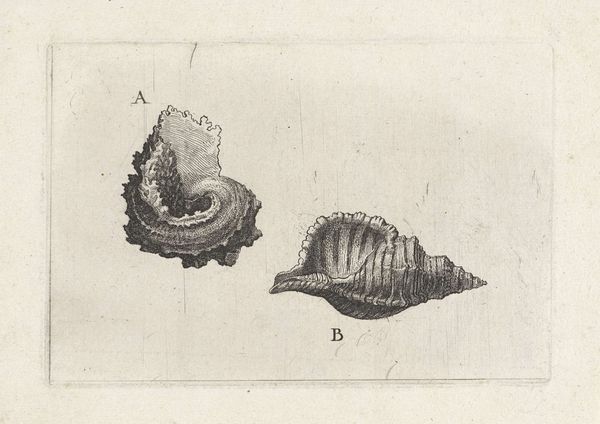

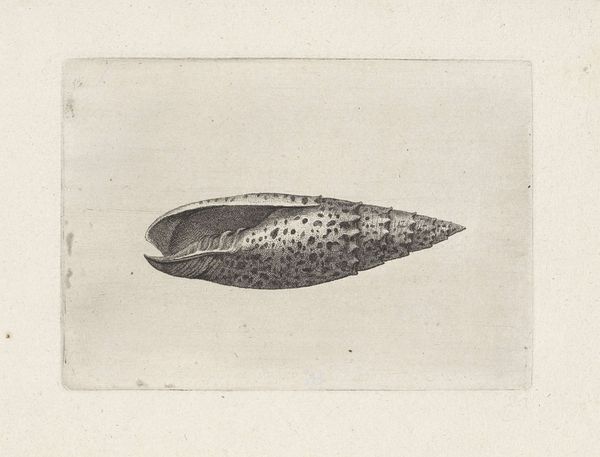

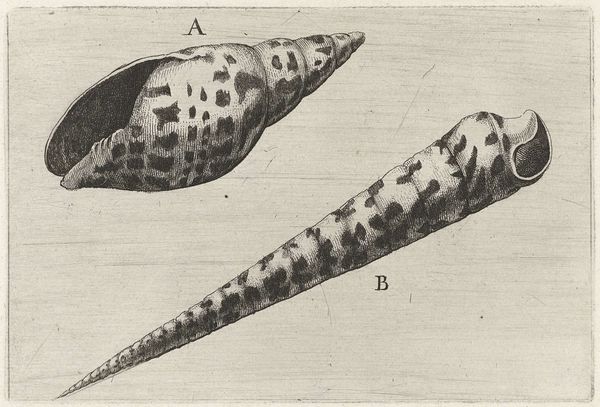

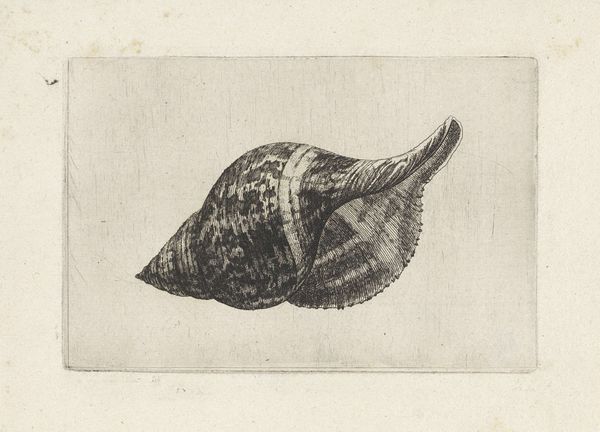

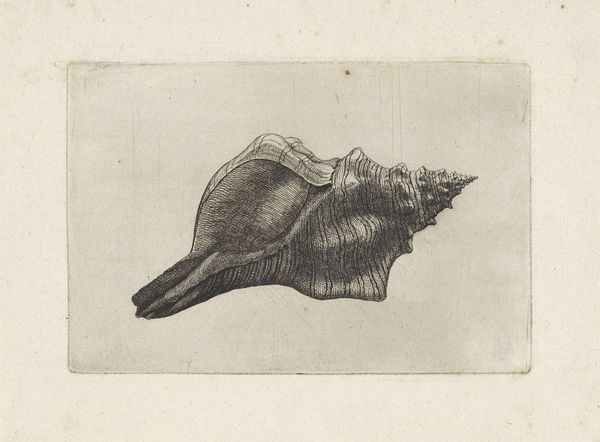

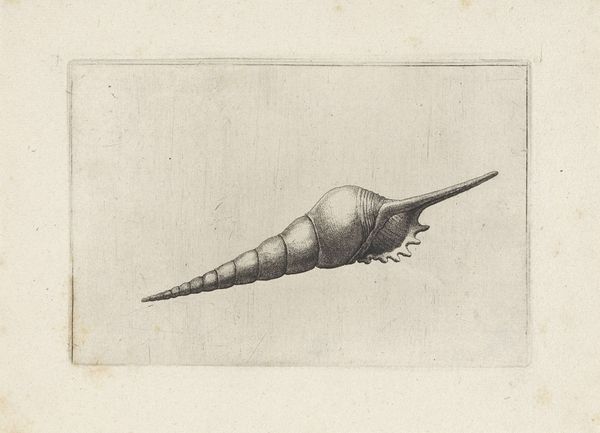

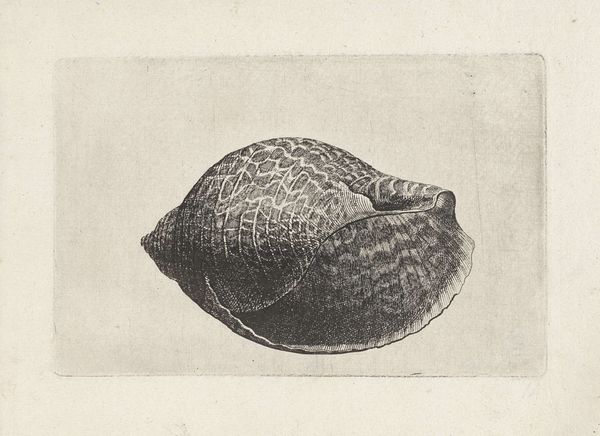

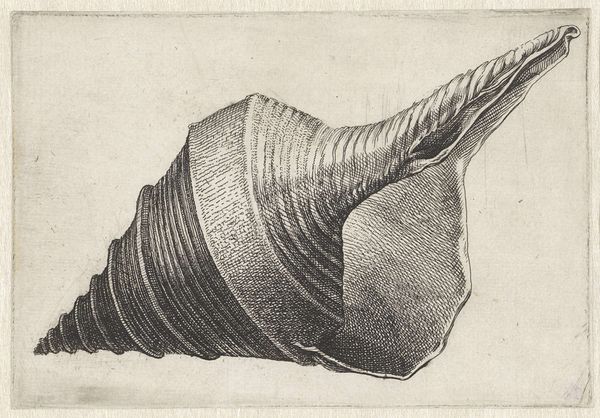

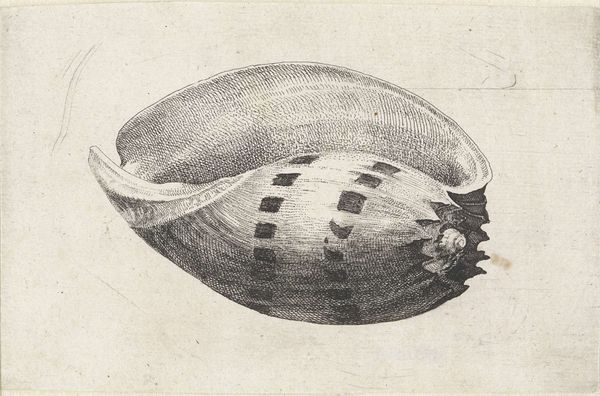

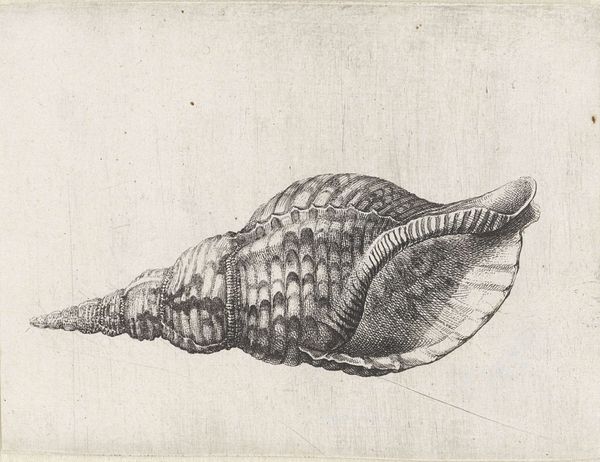

Schelpen, telescopium telescopium (A) en fusinus laticostatus (B) 1644 - 1652

0:00

0:00

wenceslaushollar

Rijksmuseum

print, engraving

#

baroque

# print

#

line

#

engraving

#

realism

Dimensions: height 100 mm, width 146 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Well, here we have a fascinating piece, a print titled 'Schelpen, telescopium telescopium (A) en fusinus laticostatus (B)' created by Wenceslaus Hollar between 1644 and 1652. It's currently held here at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: It's striking. A sort of clinical yet beautiful arrangement of the shells, so precise, like a specimen slide. It evokes a feeling of early scientific exploration, that initial attempt to categorize and understand the natural world. Curator: Absolutely. Hollar was known for his detailed topographical views and natural history illustrations. Prints like these served a crucial role in disseminating knowledge. The burgeoning field of natural history relied heavily on visual documentation. Editor: It makes me consider who had access to these images. Were they primarily for the scientific community or did they find a broader audience through popular print culture? I'm thinking about the exchange of knowledge and how that affects perceptions of colonialism, early trade routes. Were these shells linked to specific cultures and locations? Curator: That's a vital point. Shells were highly sought-after collector's items during the 17th century, often symbolizing wealth and status, becoming intertwined with the narrative of global trade. These prints offered access to such rarities without necessarily possessing the originals. It’s the democratization of access that allows scientific advancement to disseminate and promote the advancement of that colonialist ideology. Editor: Precisely. It's not simply about documenting nature but how these items, even passively, reinforce the dynamics of power and exchange. I notice the fine detail achieved through the engraving— the minute lines capture the texture so vividly. Curator: Hollar was a master of etching and engraving. His ability to render such delicate forms is extraordinary. Consider that prints were not just art objects; they served as tools, contributing to how people visualized and understood their world. And because they were reproducible and widely available, that has an even greater reach on shaping social concepts. Editor: These are, indeed, artifacts of their time. Each line speaks volumes not only about the natural world but also about the societal structures and the era’s curiosities, and anxieties, in the colonial project. It is important to remember the artist's life work and what they created under what context. Curator: A perfect observation. Thinking about Hollar’s work offers insight into art as a lens to the history, science, and culture.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.