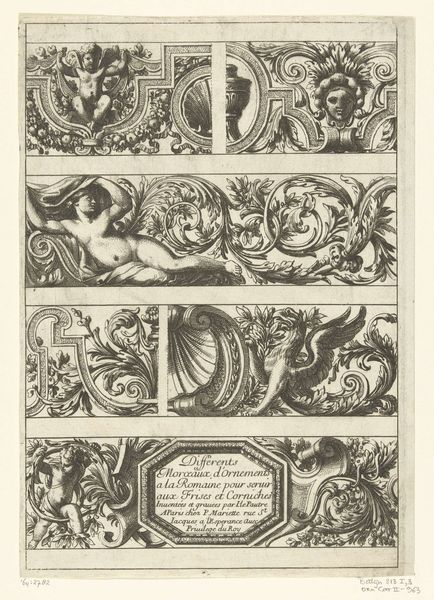

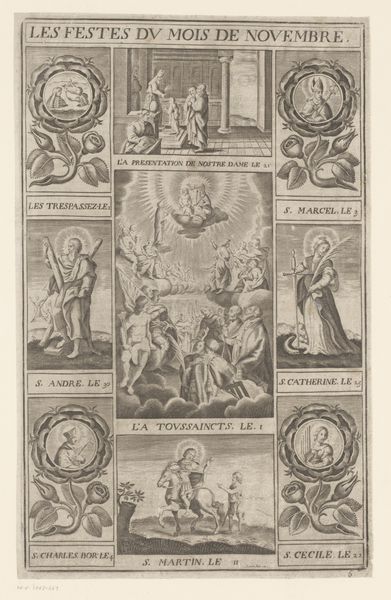

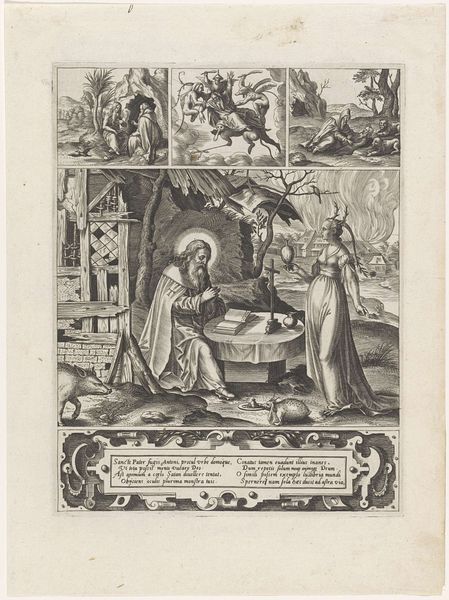

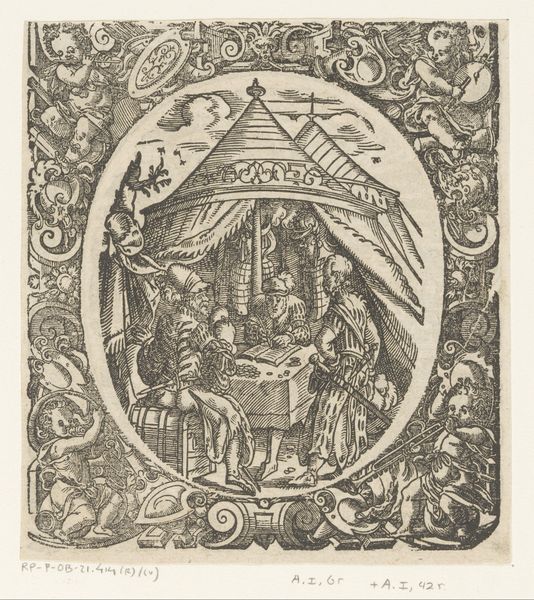

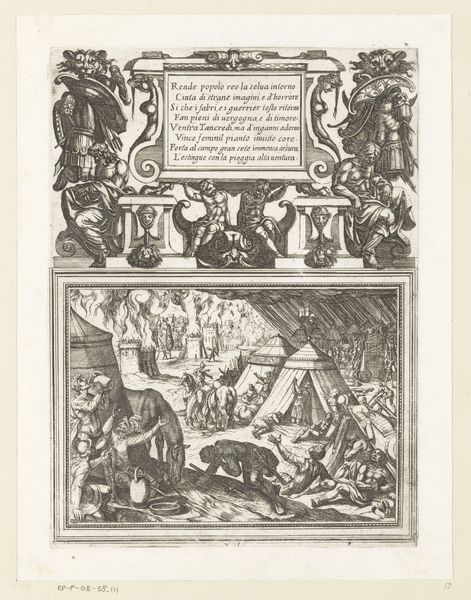

Rebekka en Eliëzer bij de put / Esau verkoopt zijn eerstgeboorterecht 1615 - 1651

0:00

0:00

anonymous

Rijksmuseum

print, engraving

#

narrative-art

#

baroque

# print

#

old engraving style

#

figuration

#

line

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 90 mm, width 39 mm, height 91 mm, width 40 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: This print, titled "Rebekka en Eliëzer bij de put / Esau verkoopt zijn eerstgeboorterecht," is an engraving that the Rijksmuseum attributes to Anonymous, and it seems to date to sometime between 1615 and 1651. I'm struck by the detail despite the small scale. What do you make of this, especially the ways these biblical stories are depicted? Curator: From a materialist perspective, let’s consider the labour involved in creating this engraving. An anonymous print suggests a specific socio-economic context, right? Perhaps intended for wider distribution, moving it from the realm of high art to something more functional, didactic even. What does the relative inexpensiveness of printmaking compared to painting do to the value assigned to image making and art consumption at the time? Editor: That's fascinating. I hadn't considered the accessibility afforded by printmaking in that way. How does that inform our reading of the stories being told, Rebekah at the well and Esau selling his birthright? Curator: Well, both narratives deal with resources—water, birthright—and their exchange. Consider the materiality of water itself in the Rebekah scene. Its life-giving properties, essential for survival. What does it mean when *that* is what is being given freely? On the other hand, Esau *sells* something fundamentally tied to his identity and social standing, a transaction visualized through the act of offering him food. How are these scenes tied to concepts of wealth and material existence for the target audience? Editor: So you are saying that even biblical scenes can speak to consumption habits of their contemporary audience? Curator: Absolutely! Religious narratives can provide insights into everyday life, offering glimpses into the values attached to tangible things and how labour, trade, and religious instruction shape material realities for ordinary people. What kind of social structures do you think enabled the creation and dissemination of a print like this, and for whose consumption? Editor: That connection really broadens my understanding. I will definitely view prints and engravings differently from now on! Curator: Glad to hear it. This just goes to show that when we shift the focus to process, materials, and social context, new possibilities can unfold.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.