Plate 25: Philip crowned King of Spain by his father, Charles V; from Guillielmus Becanus's 'Serenissimi Principis Ferdinandi, Hispaniarum Infantis...' 1636

0:00

0:00

drawing, print, engraving

#

drawing

#

baroque

# print

#

genre-painting

#

history-painting

#

academic-art

#

engraving

Dimensions: Sheet (Trimmed): 11 × 14 in. (27.9 × 35.5 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

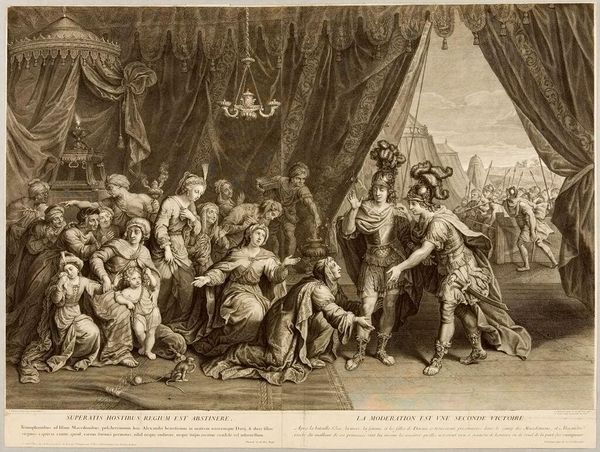

Editor: This is "Plate 25: Philip crowned King of Spain by his father, Charles V," an engraving from 1636 by Anton van der Does. The whole scene feels so staged, so deliberate. What historical context is at play here? Curator: Precisely. This isn't just a portrait; it's a carefully constructed narrative about power and succession. Consider the Hapsburg dynasty, which sought to legitimize its rule through elaborate displays like this. It reinforces a patriarchal structure but we may also note how Philip is made subordinate in that specific moment. How might the social inequalities of the era shape this representation of inheritance? Editor: I see what you mean. The focus isn't solely on Charles passing the crown, it is equally, if not more, so about visually reinforcing divine right. Were there other avenues through which such political concepts could be presented in this time? Curator: Absolutely. Think about pamphlets, public ceremonies, and even fashion. They all became vehicles for propagating ideology, especially considering the prevalence of political instability in the 17th Century. Even an artistic choice like engraving emphasizes the widespread availability of information and how a king must relate to the population and project influence. What happens if we unpack these figures' clothes, for example? What messages might they be giving us? Editor: That’s such a compelling point. The crowns, of course, but the very luxurious nature of the cloaks signal importance and are working to make very explicit claims to power and legacy. The more subtle means of communicating power is fascinating, though. Curator: Yes. By examining the intersections of art, politics, and social structures of the 17th century, we reveal the multiple, often contradictory ways power was performed, negotiated, and resisted. The work encourages dialogue, connecting past representations of leadership and inheritance to the contemporary conversation on authority. Editor: This conversation really deepened my appreciation for how much context informs even a seemingly straightforward historical image.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.