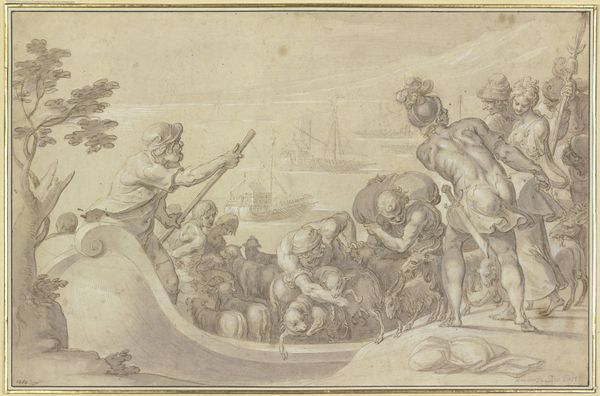

Plate 35: Philip of Spain as Neptune, riding in a chariot drawn by two sea horses; from Guillielmus Becanus's 'Serenissimi Principis Ferdinandi, Hispaniarum Infantis...' 1636

0:00

0:00

drawing, print, engraving

#

drawing

#

allegory

#

baroque

# print

#

figuration

#

engraving

Dimensions: Sheet (Trimmed): 11 5/8 × 15 1/8 in. (29.5 × 38.4 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: This engraving, dating back to 1636, is attributed to Pieter de Jode II. It's titled "Plate 35: Philip of Spain as Neptune, riding in a chariot drawn by two sea horses; from Guillielmus Becanus's 'Serenissimi Principis Ferdinandi, Hispaniarum Infantis...'" and we're fortunate to have it here at the Met. Editor: It's…intense. So much activity! All these fantastical sea creatures pulling and carrying Philip of Spain—or, well, the allegory of him as Neptune. There’s such detailed work in rendering textures. Curator: Absolutely. The Baroque period thrived on allegory and spectacle. This image was part of a larger publication documenting royal entries and celebrations. Consider how ephemeral these events were, existing only for a brief time; prints like this became crucial for disseminating political power and projecting an image of authority. Editor: It is fascinating how much detail went into immortalizing a singular political moment into something repeatable, for broader circulation. Look at the line work: the rippling water, the scales on the sea horses, the textures of those building facades. There's this interplay between representing reality and pure fantasy; this imagined procession blends into very real architectural backgrounds. I'd love to know how involved the workshops would've been for the engraver and how much that factored into final image we see here. Curator: Exactly! Prints like these served almost as early forms of political propaganda. Displaying wealth, control and power. Editor: Yes. Neptune with very contemporary Dutch architecture. It's almost a study of contrasts – timeless mythical figure juxtaposed with tangible depictions of place. But again, someone had to have meticulously created this matrix used to spread the image for years to come. That material process deserves notice as much as the royal connection. Curator: Indeed. By examining the circumstances around the artwork's production, including royal patronage and public events, we can understand how images solidified power structures during this historical moment. Editor: Well, I leave seeing the immense planning but even labor involved to produce prints to create or recreate such fleeting public celebrations! The artwork is as much about statecraft, I think, as it is a moment of intensive making.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.