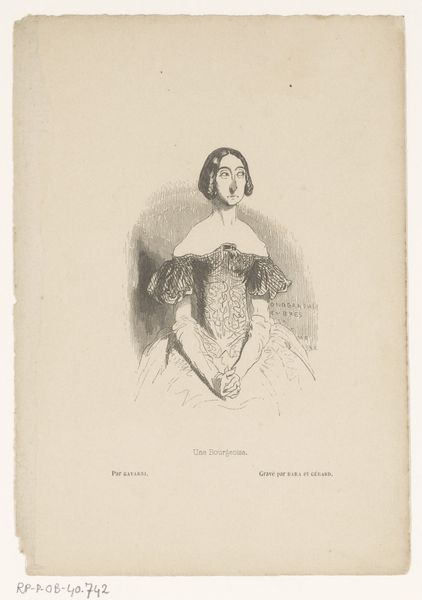

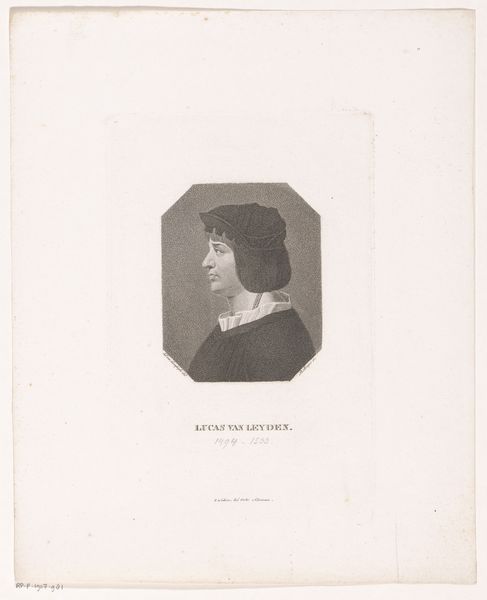

print, engraving

#

portrait

# print

#

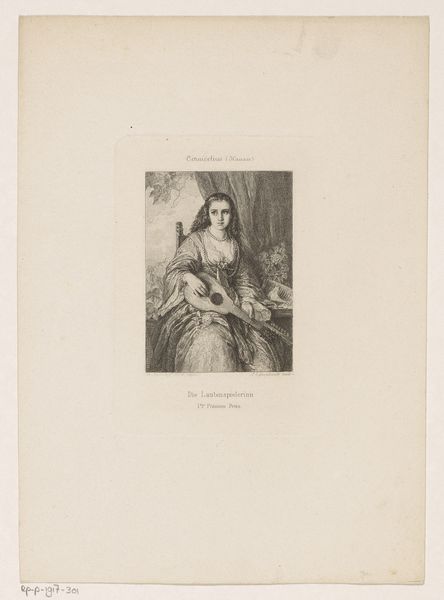

pencil sketch

#

engraving

#

realism

Dimensions: height 277 mm, width 201 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This is a print from 1867 by Léopold Flameng, titled "Portret van Antonia Duvauçey de Nittis." It's an engraving. Editor: My goodness, she looks utterly captivating, almost melancholic. There’s such grace in her posture and a kind of knowing in her eyes. I feel like I could sit and share secrets with her, you know? Curator: Flameng was a master engraver, and here, his skills are really on display. Prints like this offered a wider circulation of portraiture, democratizing access to imagery of elites. It’s also relevant when examining representation, as these images shape our understanding of gender roles within 19th century bourgeois society. Editor: True, she embodies an era. The velvet of her gown seems almost touchable through the etching, but that controlled beauty also has an air of restriction about it. You can't help but wonder, you know, what were her own desires, her ambitions? I picture her, a writer perhaps, secretly scribbling in a hidden diary, expressing thoughts deemed improper for a woman of her standing. Curator: Those tensions are definitely present if you look beyond the composed surface! While the details depict affluence, they can also read as constraints. Consider how female representation and agency are negotiated in portraiture—it is hardly a passive act but instead a stage for active and nuanced negotiation. Editor: Precisely! And the fact that it’s an engraving… each line painstakingly etched, echoes that control. It's beautiful, yes, but like a perfectly caged bird. I wonder, what did she really think of sitting for the portrait? It probably was more chore than privilege, more societal pressure than a personal choice. Curator: Exactly, we're dealing with performance. It makes you reflect on power dynamics, class and how portraits are so intertwined with the construction of identity. Thinking critically, what social and economic opportunities were open to women like Antonia? How might the art world have either reflected or perpetuated particular roles? Editor: Well, that has really brought a whole other layer of perspective. She now represents more than just a poised portrait, but also a quiet story of longing and constraint within all that visible wealth. Curator: Precisely. And it is in acknowledging the intersectional context that artworks speak in diverse ways today.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.