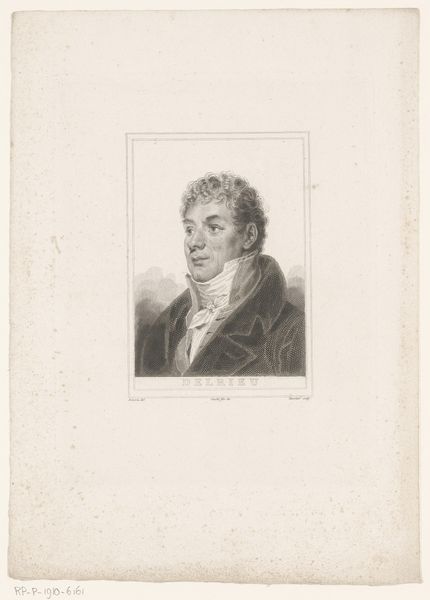

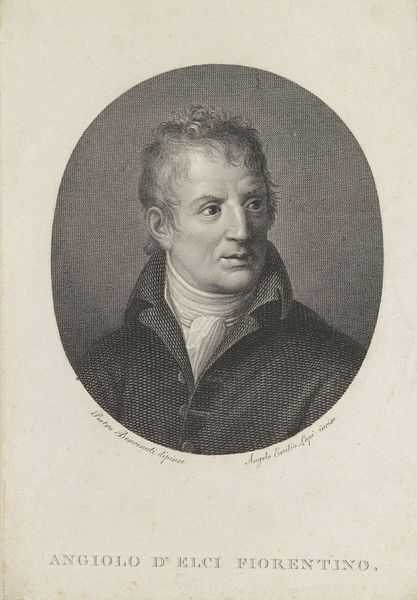

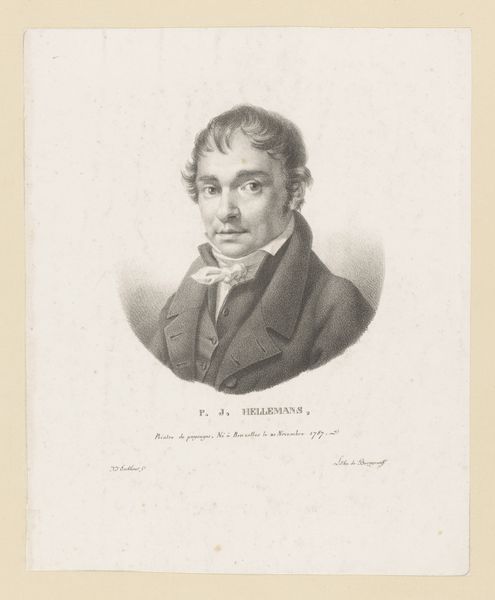

drawing, print, graphite, engraving

#

portrait

#

pencil drawn

#

drawing

#

neoclacissism

# print

#

old engraving style

#

form

#

pencil drawing

#

line

#

graphite

#

academic-art

#

engraving

#

realism

#

monochrome

Dimensions: height 128 mm, width 97 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Upon first viewing, this piece feels rather serious and austere. The monochrome palette certainly contributes to that feeling. Editor: Indeed. This is "Portret van W. Borneman," created in 1816 by J. Meyer. The medium appears to be an engraving, likely printed. Considering the time period, we're squarely in the Neoclassical movement. Curator: And that informs much about its creation. Notice how the precise linework emphasizes the sitter's form. An engraving requires immense technical skill; the craft of producing clean lines repeatedly on a metal plate speaks to a certain ideal of reproducible, accessible imagery. Were these portraits like this broadly distributed? Editor: To an extent. Engravings allowed for a wider distribution of images compared to unique painted portraits. Consider how portraiture reinforced social hierarchies; its relative accessibility meant a burgeoning middle class could engage with it, albeit in a different format. The image of power became available for replication, even if the access to actual power did not. Curator: Interesting. So, beyond its Neoclassical style, the engraving itself speaks to an emerging economy of images and perhaps an aspiration to a lifestyle, that’s only been recently available due to industrial shifts and increased production, wouldn't you say? The stark presentation allows for detail in production too. Editor: Precisely. Furthermore, the decision to render the subject in this particular manner communicates status and seriousness. He's wearing what looks like a military uniform and a possible medal - suggesting, you know, civic duty or service. How images project meaning in a social context is key to me. Meyer isn't merely rendering Borneman; he's contributing to the construction of a public persona. Curator: It makes me consider the engraver’s own position in the whole exercise of image production; their agency in relation to both patron and subject and their participation in, not merely picturing, social hierarchies, but reproducing the images for it. Editor: Absolutely. The portrait, therefore, isn't just a representation of an individual, but also evidence of shifting social and material conditions during a crucial moment of change. Curator: I hadn't thought of it in quite that light; thinking of materials and context enriches the image so much! Editor: Thank you, looking at this, its historical setting, and how this reflects social standing has definitely informed me.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.