photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

portrait

#

photography

#

historical photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

Dimensions: height 135 mm, width 95 mm

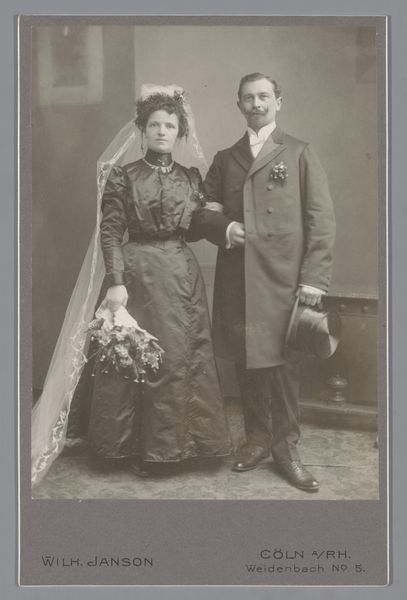

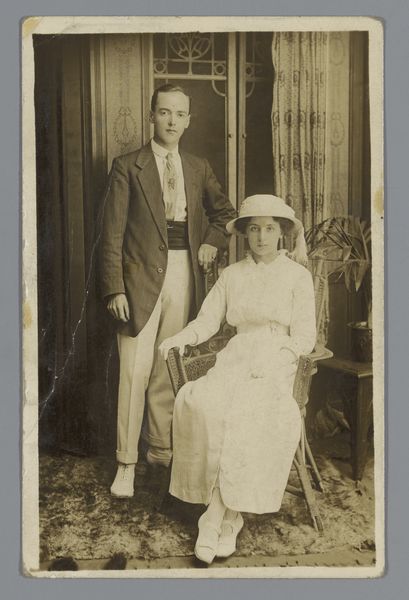

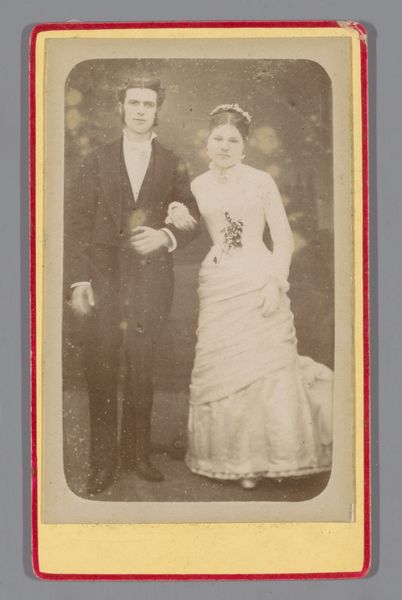

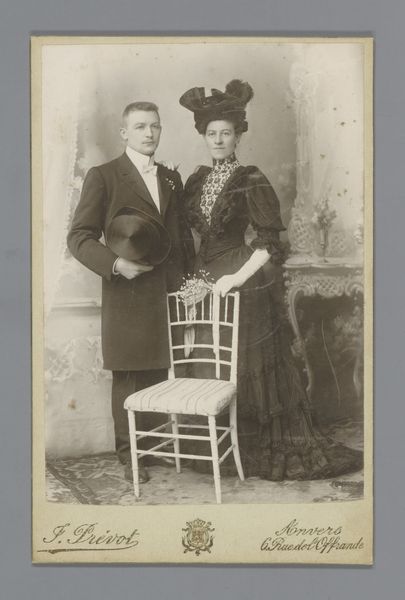

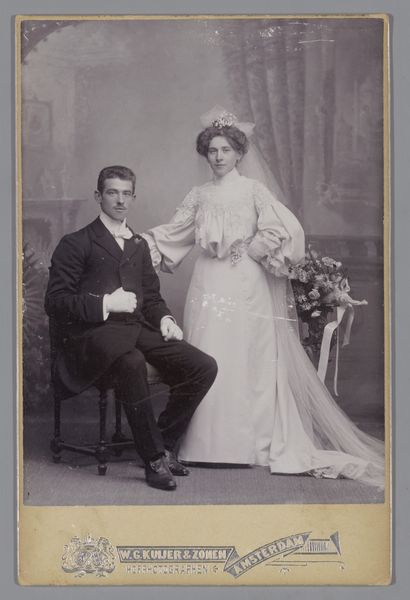

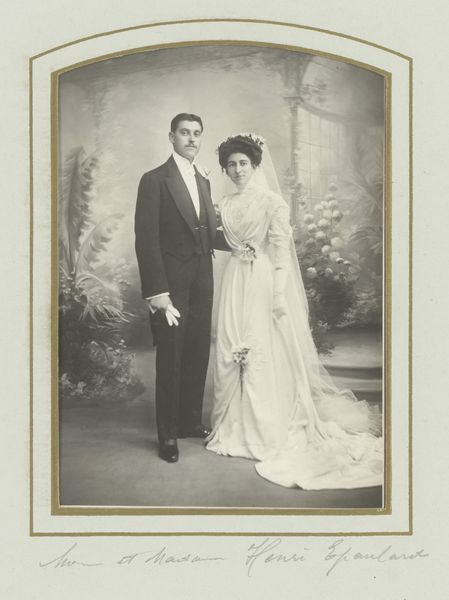

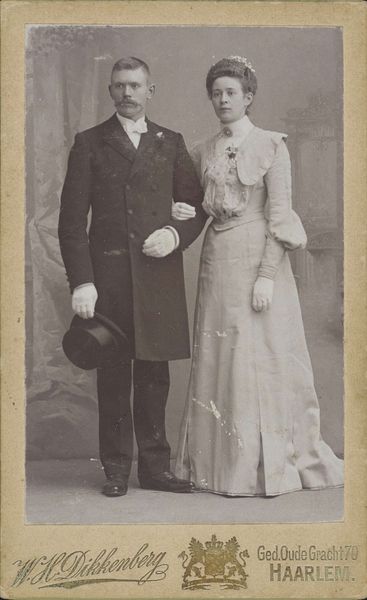

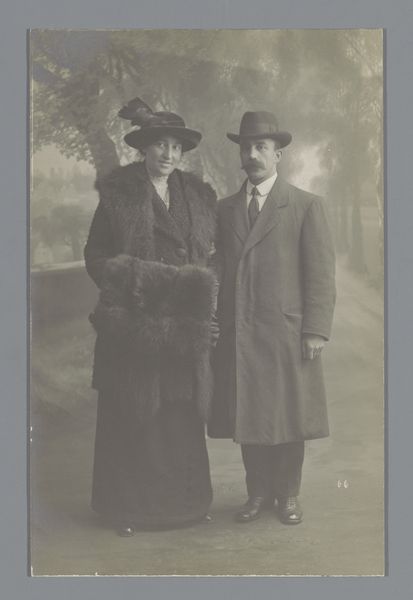

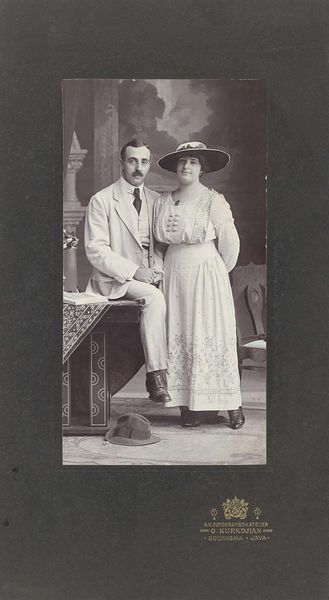

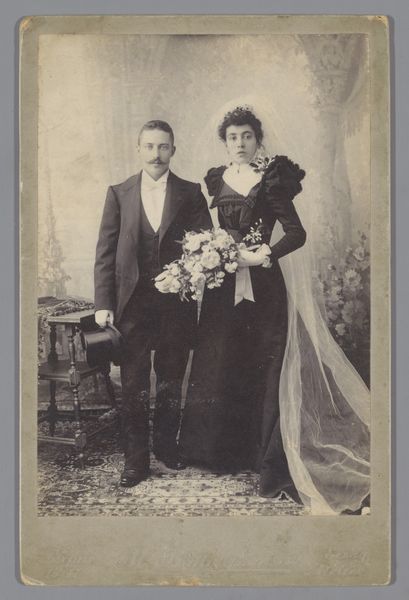

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Before us, we have “Portret van een echtpaar,” a photographic portrait, dating roughly from 1890 to 1930, created using a gelatin-silver print process. Editor: The sepia tones lend it such a nostalgic air, don’t they? You immediately get a sense of formality and perhaps a slight detachment between the couple. Curator: The materials absolutely inform that formality. Gelatin-silver printing, standardized at this point, allowed for mass reproduction of images, solidifying the studio portrait as a way for even the middle class to perform status and memorialize themselves. Think about the industrialization behind even "intimate" portraiture. Editor: And you see the deliberate staging – they’re on a staircase, a small decorative chair is placed precisely to the side... it speaks to a performance of upward mobility, wouldn’t you say? The societal role of this image was as a testament to the couple’s position within their community. Curator: Indeed. The staircase, that partially visible chair. Consider too the materials of their clothes –wool, likely mass-produced yet carefully tailored and styled. The photograph functions not just as an image but also a testament to consumer access and textile production innovations of the period. Editor: There’s such a strong feeling of an era passing, too. We see not just a picture of individuals, but a society caught in transition. How were these images viewed? And did they function solely as mementos? Curator: We should certainly consider circulation. Prints like this were readily reproducible, which made sharing them simple: cartes de visite or cabinet cards of individuals were commonly distributed. In short, what do people *do* with photos? They display them. They exchange them. Photos became another element within Victorian material culture used to cultivate relationships or networks. Editor: It's fascinating to consider its social impact when something seemingly intimate such as a photograph becomes so easily reproducible, changing from something deeply personal to widely socialized. Curator: Absolutely. By looking closely at materiality and production we’ve learned not just about these two individuals, but about the rise of photography and its profound societal role. Editor: A wonderful reminder of how understanding context deepens our connection to the image and prompts important questions about identity, access and history.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.