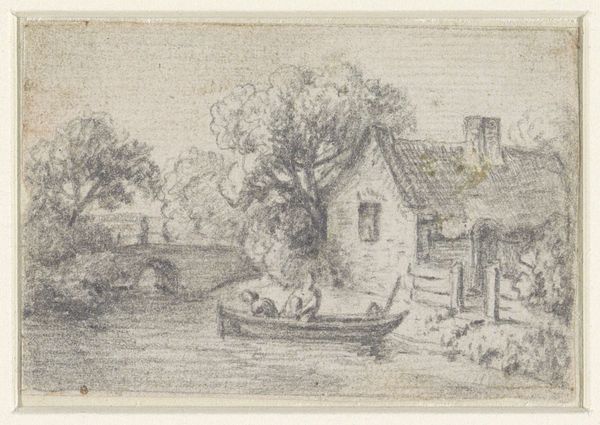

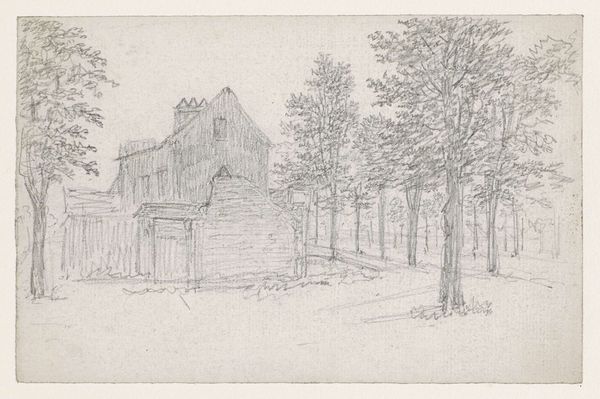

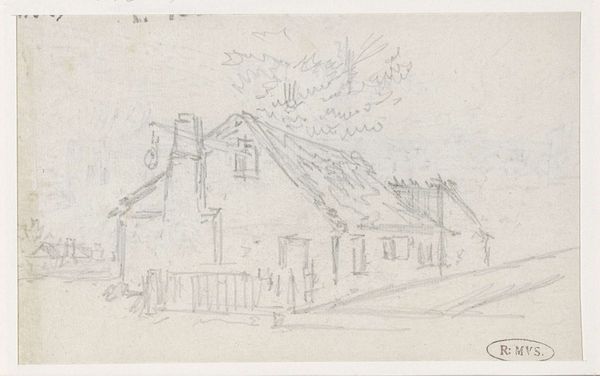

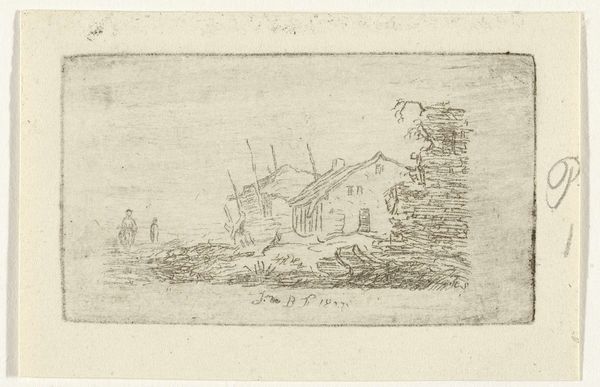

drawing, pencil

#

drawing

#

landscape

#

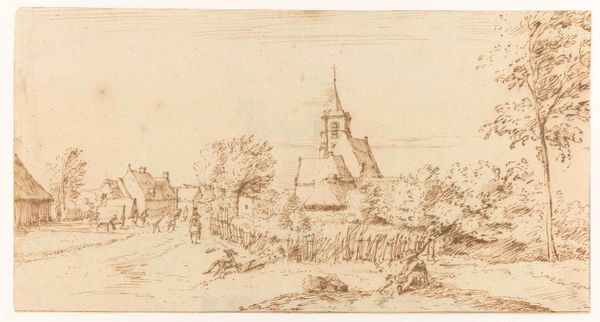

etching

#

pencil

#

realism

Dimensions: height 131 mm, width 208 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This is Jozef Israëls' "View of a Village with a Church," a work on paper rendered in pencil, dating roughly between 1834 and 1911. It’s currently held here at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: My first thought? Sparse. The bare outlines of the buildings, the almost scribbled-in sky... it has a feeling of something not quite finished, or perhaps deliberately raw. You can see the texture of the paper itself, which makes it seem quite intimate. Curator: Indeed. Israëls, deeply embedded in the Hague School, sought to depict the lives of ordinary people with a stark realism. His choices, including this visible pencil work, were highly deliberate. What might look unfinished is, I would argue, an intentional move toward honesty. It connects to a broader artistic and social ethos aimed to elevate humble, rural existence by displaying truthfulness in artistic practice. Editor: The materials absolutely speak to that. Pencil on paper is such a direct, unpretentious medium. It suggests accessibility – anyone could pick up a pencil and try to capture their own surroundings. I wonder what paper Israëls used here? Was it a common stock, or something finer chosen specifically to catch the delicate marks? It matters when we think about who could consume or emulate such images. Curator: His focus on portraying peasant life must be seen as a product of the Realism movement. There were rising waves of nationalism in the 19th century. As urban life expanded through industrial labor, artists found significance in more provincial ways of life. This wasn't merely aesthetic, but political, contributing to a certain idealized image of the Netherlands. Editor: I’m more concerned with the implied labor here. I notice that despite being ‘raw’, this scene offers detailed precision regarding shapes. If we consider materiality, what could Israëls do with quick mark-making? In this way, how did it inform an understanding of working conditions for laborers in industrialized Holland? It asks us to consider those unseen people in the foreground. Curator: Absolutely, and his portrayal—while celebrated—has faced critiques for idealizing rural life, simplifying social complexities. It begs the question, for whom were these images made and how might those views have informed and shaped policies for Dutch national identity in the late 19th century? Editor: So, from the deliberate crudeness of materials to the societal implications of this drawing, it clearly resonates with questions that move us past a merely superficial rendering. It calls on us to engage in broader and socially charged questions of identity, value and artistic intent. Curator: Precisely. A seemingly simple sketch unveils the web of political tensions beneath 19th-century artistic production and reception.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.