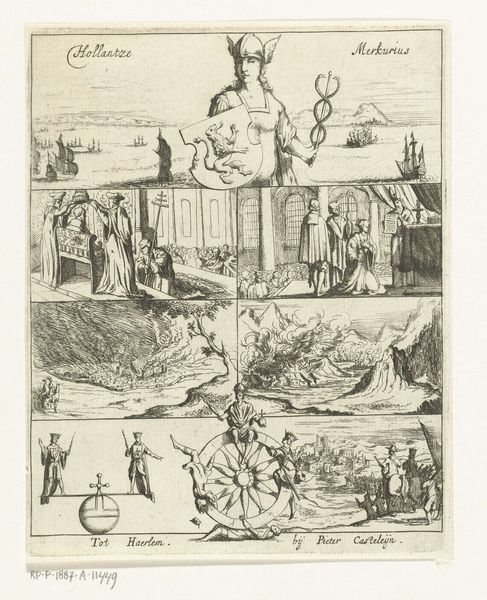

Jongen geknield bij de spaken van een wiel en een perspectiefstudie 1707 - 1740

0:00

0:00

drawing, print, etching, engraving

#

drawing

# print

#

etching

#

perspective

#

11_renaissance

#

geometric

#

history-painting

#

academic-art

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 176 mm, width 125 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have Jan de Lairesse's engraving "Jongen geknield bij de spaken van een wiel en een perspectiefstudie," created sometime between 1707 and 1740. What are your initial thoughts? Editor: The stark lines immediately strike me. There’s a coldness to the perspective exercise, even though there’s also an attempt at evoking classical idealism. Curator: Yes, the coolness feels very academic. It's not simply about visual skill, though. Academic art during this era often sought to create allegories accessible to an educated elite. We can see here an embodiment of classical perspective being "discovered" by the kneeling boy, reminiscent of artistic "re-birth". How does that reading influence your symbolic understanding? Editor: Interesting! Knowing that, the boy becomes an archetype – an apprentice of sorts learning the ancient mathematical systems of the world. He kneels not just in study but almost in reverence. The wheel and the distant landscape carry weight now, speaking to a continuity of knowledge passed down. Curator: Precisely. Consider, also, that linear perspective itself was gaining prominence again, used as a tool of power by the elite, a 'scientific' representation lending itself to increasingly realist modes of portraiture that reinforced power dynamics. Editor: That certainly adds a layer of complexity. The grid below then isn't just a guide, it's also a representation of power, controlling the subjects within the pictorial space. The shadows even seem like extensions of that controlling force. Curator: A compelling insight. These perspective studies weren’t just exercises, they served a function, didn't they? Teaching us not just how to depict the world, but how to construct a certain viewpoint *of* the world. Editor: Absolutely. Even the figures themselves seem staged, their gestures calculated rather than organic. The objects like vases spaced in perfect measure speak of controlled environments and constructed hierarchy. Curator: So, we end where we began—recognizing that technique can contain multiple readings, as the symbols take on complex historical, social, and personal meanings, challenging even our present understanding of visual culture. Editor: Indeed. The print now becomes far more than an exercise in spatial construction but a key into an entirely constructed historical world.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.