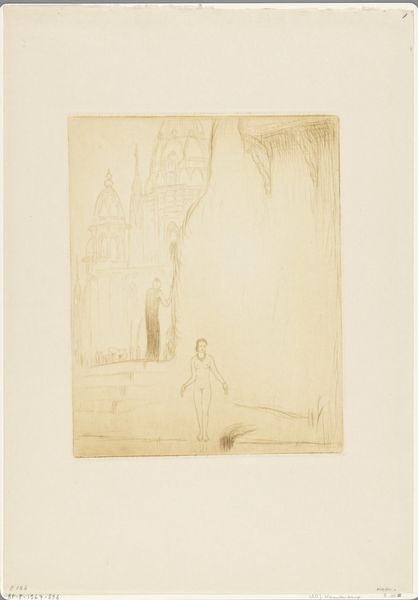

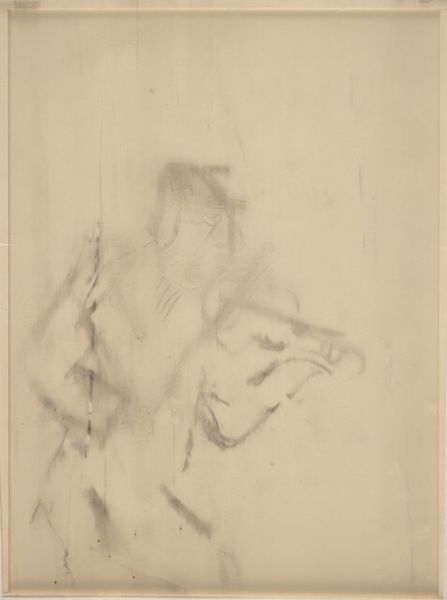

drawing, pencil

#

drawing

#

water colours

#

figuration

#

pencil

#

orientalism

#

line

#

nude

Dimensions: height 247 mm, width 197 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

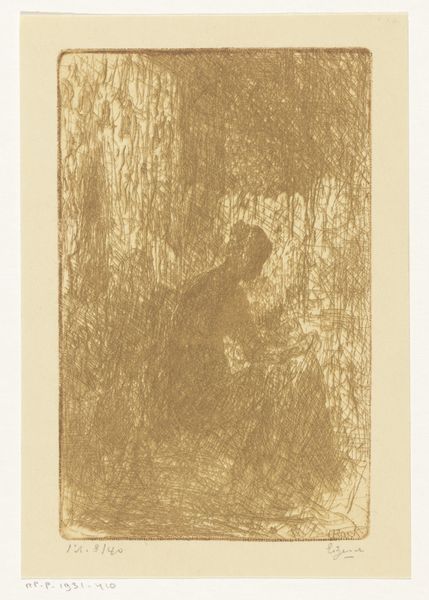

Curator: This delicate drawing, possibly from 1917, is entitled "Bathing Girl on the Banks of the Ganges in Benares," by Wijnand Otto Jan Nieuwenkamp. It’s rendered with pencil and watercolor. What strikes you about it? Editor: It has a haunting quality. The minimalist lines and the vast expanse of untouched space evoke a sense of both vulnerability and profound stillness. The figure seems so isolated within this muted landscape. Curator: Nieuwenkamp, working in the Orientalist style, presents us with a scene imbued with cultural significance. The Ganges River, especially in a holy city like Benares—now Varanasi—holds deep spiritual meaning. A bathing woman carries layers of symbolic weight. How does that inform your reading? Editor: It forces me to consider the gaze. While the style draws from Orientalism, which can be problematic due to its exoticizing tendencies, the simple composition feels almost respectful. Is it documenting a cultural moment, or subtly fetishizing it? Where does representation stray into objectification in pieces such as this one? Curator: Precisely! And we should remember the social context: Nieuwenkamp, a European artist, capturing this intimate moment. The artistic choices—the nude figure, the setting on the Ganges—participate in a colonial discourse that we need to address critically. The 'serene' image then gets tied up with unequal power dynamics. Editor: The act of bathing transcends mere physical cleansing, especially in the Ganges; it represents spiritual purification. It makes me question whether Nieuwenkamp, irrespective of intention, understood and valued the profundity or approached this solely with a voyeuristic impulse? I see the drawing almost as an ethnographic observation, colored with subjectivity. Curator: Nieuwenkamp lived for extended periods in the Dutch East Indies. His engagement with non-Western cultures was complex. While not excusing problematic aspects of Orientalism, we must also examine his works within his specific historical context to reveal social relations of the era. He saw himself, perhaps mistakenly, as understanding these cultures. Editor: This work makes us face those complexities. What begins as a seemingly tranquil scene sparks deeper questions about representation, power dynamics, and cultural exchange. Curator: Ultimately, examining Nieuwenkamp’s work offers critical insight into how cross-cultural artistic exchange can replicate skewed power relationships while expanding the visual language in art. Editor: Absolutely. By deconstructing what might appear like an "innocent" depiction, we unravel deeper significances to art’s engagement with society.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.