photography, albumen-print

#

landscape

#

photography

#

ancient-mediterranean

#

orientalism

#

cityscape

#

islamic-art

#

albumen-print

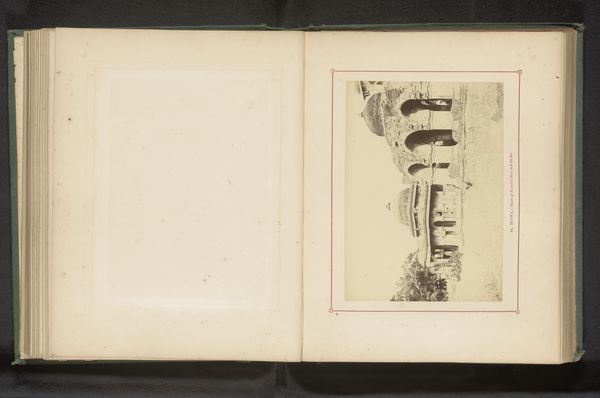

Dimensions: height 135 mm, width 187 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

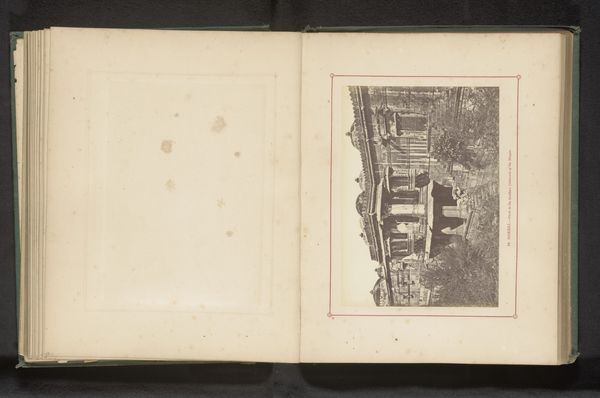

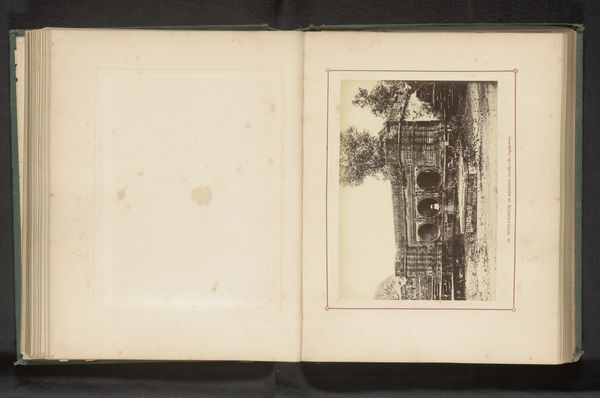

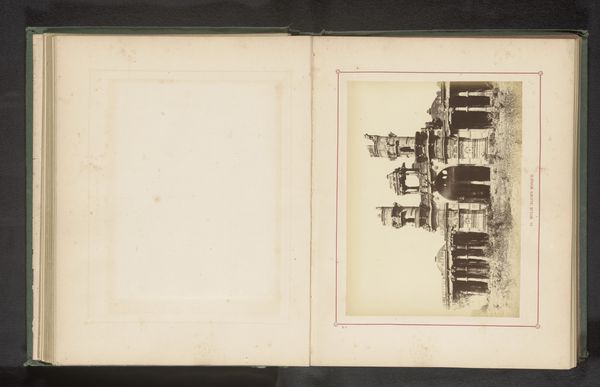

Curator: Here we have an albumen print titled "Gezicht op de Miya Khan Chishti-moskee in Ahmedabad," dating back to before 1866. It's attributed to Thomas Biggs and beautifully captures a scene of Islamic architecture in India. What strikes you first about it? Editor: Well, besides its obvious documentation of place, the weathered stones give me this immediate impression of permanence and history, almost melancholy in its silence. It speaks of echoes, doesn't it? Curator: It absolutely does. It was made during a time when photography served as a tool of imperial documentation. Photographs like this were disseminated widely. The aesthetic fascination with "the Orient" contributed to the construction of a Western understanding of non-Western cultures. It reflects how Islamic art and architecture were perceived and categorized in the colonial era. Editor: Right, but those visual symbols—the archways, the intricate carvings on the pillars—they have an inherent spiritual weight outside of any political context. Those forms still point to a long line of cultural transmission. This architectural language, even frozen in a colonial photograph, evokes centuries of devotion. Curator: But doesn’t the very act of its capture—being selected, framed, and then disseminated across the Empire—change that meaning? Photography played a direct role in reinforcing these power structures. Images had serious implications in justifying British rule in the subcontinent. Editor: I acknowledge that layer of power, of course. Yet, I see a resilience too. Even now, looking at it, I feel transported—not just by its composition but because those archetypal forms still trigger something ancient within the psyche. It invites us to reflect on civilizations—rise, fall, continuity, the universal search for meaning and expression through symbols. Curator: And what about that specific search taking place against a complex framework of colonial interests and biases? How did this type of work shape opinions and consolidate a particular narrative? The beauty of the image doesn’t negate these things. Editor: Of course not. In the end, understanding the interplay of these layers makes the work so powerful: both the photograph itself as a historic object and what we, as viewers, project upon those symbols and representations from our own vantage points today. Curator: Indeed. Seeing the architecture, reading its symbols, questioning its making—each gives a fuller view.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.