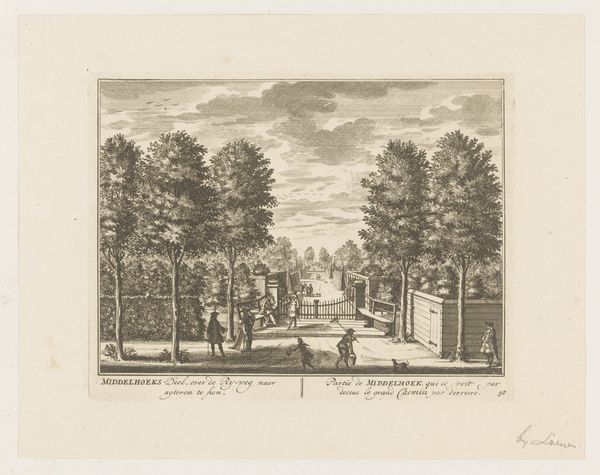

print, engraving

#

dutch-golden-age

# print

#

old engraving style

#

landscape

#

river

#

cityscape

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 162 mm, width 201 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: So, this is "Gezicht op Goudestein," an engraving made in 1719 by Daniël Stopendaal. It's a detailed cityscape, and I’m struck by how it presents this idealised view of leisure and prosperity. What stands out to you in this image? Curator: Immediately, I see the way the print mediates social status in the Dutch Golden Age. Consider the very act of commissioning and disseminating such an image. It speaks volumes about the patron’s desire to project power and taste. How does the setting contribute to that projection? Editor: I guess the orderly canal and the meticulously rendered buildings suggest control and wealth. The figures strolling casually along the waterway also paint a picture of serene upper-class life. Curator: Precisely. And notice how the landscape isn’t merely a backdrop but a carefully constructed stage. The politics of imagery in this era were heavily influenced by wealthy patrons who wanted to broadcast their values. The museum itself, displaying this image centuries later, continues that act of making the private public. How do you see this image interacting with the museum space now? Editor: It makes you wonder about the ethics of displaying such potent imagery, almost romanticizing a history built on potentially unequal power dynamics. But perhaps displaying it allows for that critical examination? Curator: Indeed. We learn as much from the visual culture as we do from written records about how societal structures were maintained. Examining the public role of art like this gives us the ability to critique these portrayals. Editor: This has shifted how I perceive these seemingly quaint cityscapes. There’s a lot more to consider below the surface! Curator: Absolutely. Engaging with the social and historical contexts transforms a simple landscape into a complex historical document.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.